(Click on images to enlarge)

R. M. Schindler, 1927. Edward Weston portrait. Owned by Sam and Harriet Freeman. Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents. From Saving Wright: The Freeman House and the Preservation of Meaning, Materials and Modernity by Jeffrey M. Chusid, Norton, 2011, p. 139.

Playbill for "The Idiot" by Fyodor Dostoyevsky as adapted by Reginald Pole and John Cowper Powys, Belmont Theater, January 25th and 28th, 1928. Courtesy UC Santa Barbara Art Museum, Architecture and Design Collections, Schindler Collection.

The genesis for this article was the discovery of the above playbill in the papers of architect Rudolph M. Schindler at the University of California Santa Barbara Art Museum's Architecture and Design Collections. The play, an adaptation of Fyodor Dostoyevsky's "The Idiot" by Reginald Pole and John Cowper Powys, included a fascinating cast of mutual friends of both Schindler and his wife Pauline and photographer Edward Weston such as Reginald Pole and his then wife Frances, Pole's former lover Beatrice Wood, Weston portrait sitter and Schindler client and divorce attorney Anna "Olga" Zacsek, and Boris Karloff. Schindler designed the stage sets for "The Idiot" and was also credited as art advisor. Weston wrote in his Daybooks about attending the play and, after her performance, partying with Zacsek at the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed house of Sam and Harriet Freeman for whom Schindler also designed many revisions and furniture. (The Daybooks of Edward Weston, Volume II, California, p. 47).

The playbill opened up numerous avenues of research which resulted in the following article. I intend this work to become a chapter in a much broader work encompassing the familial relationships between the Schindlers and the Westons and their radical, bohemian, avant-garde coteries in Los Angeles and Carmel. In this piece, which focuses mainly on their mutual friends in the dramatic community, I intend to interweave the stories of Anna Zacsek, Reginald Pole, Helen Taggart, Lloyd Wright, Kirah Markham, Beatrice Wood, Frayne Williams, Florence Deshon, Max Eastman, Charlie Chaplin, Margrethe Mather, Tina Modotti, Aline Barnsdall, Norman Bel-Geddes, Theodore Dreiser, Helen Richardson, Paul Jordan-Smith, William J. Dodd and many others within the context of the Schindler-Weston friendship.

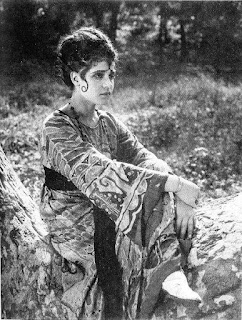

Anna Zacsek, screen name Olga Grey, 1916. Photographer unknown. From "Gallery of Picture Players," Motion Picture Magazine, November 1916, p. 25.

Anna Zacsek, 1919. Edward Weston photograph. From George Eastman House courtesy of Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

Emily J. Valentine, Founder and President, Los Angeles Conservatory of Music. Photographer unknown. From Los Angeles Herald, December 19, 1909, p. 54.

Anushka "Anna" Zacsek was the child of Stefan and Theresa Zacsek, Hungarian immigrants who moved to Los Angeles from New York around 1902. They lived at 2231 Sunset Blvd. near the movie studios and bohemian artists and actors that would shortly populate the nearby Edendale neighborhood. (For much more on the Zacsek's Echo Park residence see "Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the 2233 ½ W. Sunset Blvd. Home"). By 1908 the Zacseks had enrolled their children Anushka "Annie" and Stefan in classes at the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music and Art which was founded by Emily J. Valentine (see above) in 1883. (Author's note: With the help of Walt and Roy Disney, the Conservatory merged with the Chouinard Instiitute of Art in 1961 to form the present day CalArts).

Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) Building, 207 S. Broadway, E. A. Coxhead, architect, 1888. ("Y.M.C.A.; They Get Themselves Into Court Over Building," Los Angeles Times, May 19, 1888, p. 2). Photographer C. C. Pierce, ca. 1900. Los Angeles Conservatory of Music & Art under gable right of flag. Courtesy USC Digital Library.

Anna attended piano and elocution classes at the Conservatory which was located in the YMCA Building (see above) when Zacsek began classes there. At the age of 11 she performed a piano solo in a year-end concert with selected Conservatory classmates at Symphony Hall in the Blanchard Building (see below) under Valentine's direction. The Los Angeles Herald listed Annie Theresa Zacsek's piano recital and her certificates in piano and elocution along with her brother Stefan, and mentioned her being named one of the school's eleven "Prize Pupils." ("Musical World," Los Angeles Herald, June 24, 1908, p. 6). The Conservatory moved to the brand new Walker Auditorium Building the following year along with some other drama and music schools creating somewhat of a center for performing arts education. (See two below).

Blanchard Building, Symphony Hall, 233 S. Broadway, ca. 1921. A. M. Edelman, architect, 1899. From Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection. (See "Building Devoted to Music and Art," Los Angeles Times, January 1, 1899, p. I-29 for a complete description and floor plans of this building built by Harris Newmark and leased to F. W. Blanchard).

Walker Auditorium Building, 730 S. Broadway, July 1946. Eisen and Son, architects, 1909. Courtesy Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

Morosco-Egan School of Dramatic Arts ad, Los Angeles Herald, October 9, 1909, p. 2.

Another prominent period performing arts school, the Morosco-Egan Institute of Dramatic Arts, was formed by Frank C. Egan and Majestic Theater Building lessee Oliver Morosco in 1909 after Egan's recent arrival from from the east via Seattle. Egan advertised regularly (see above) and relentlessly promoted his dramatic productions and the achievements of his graduates in the local press. For example in a 1911 Times article Egan, who had by then bought out Morosco's interest in the school, talked of the success of his students in Chicago and on Broadway and plans for his own traveling troupes. Of his school's plans to focus on foreign drama he said,

"One's drama education is not complete unless one knows the drama of the world. To be thoroughly acquainted with the drama of America and England, which, histrionically speaking, are one country, and not to know anything about thee great dramatic movements in Germany, the essentials of modern French plays and the comedy spirit in Italy, is like completing a common school education and omitting all knowledge whatsoever of geography." ("To Send Out Own Companies: Frank Egan Considering New Production Venture," Los Angeles Times, December 31, 1911, p. III-12. See also "Egan Returns With New Names," Los Angeles Times, August 13, 1911, p. III-2).

Egan School ad. Los Angeles Times, December 31, 1911, p. III-5.

Likely attracted by Egan's advertising of his drama faculty, the Zacseks also enrolled Anna and Stefan in acting classes there evidenced by a Los Angeles Herald article reporting on their performance of a scene from "If I Were King" in the school's auditorium on the top floor of the Majestic Theater Building (see below) at the end of the 1910 school year. ("Egan Thespians Open Many Eyes at Recital," Los Angeles Herald, June 24, 1910. p. 3). The busy Anna continued her piano classes at the Conservatory a block north on Broadway and performed in two ensemble pieces just four days after her and Stefan's stage performance at the Egan School. ("Musical," Los Angeles Herald, June 26, 1910, p. III-14). The Zacseks were presciently positioning Anna for her early career in the movie business.

Hamburger Majestic Theater Building (left), 845 S. Broadway, Edelman and Barnett, architects, 1908. Hamburger's Department Store (later May company) on right. Courtesy of Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

In an article discussing the success of the girl students from his school Egan said,

"Los Angeles has produced some mighty clever boys, but so far the ambitious girls are far in the lead. Many of them are going out in prominent positions in western organizations. Some of them are going straight to Broadway. "Young women that have been sent out from the Egan School during the past year are playing as far West as Honolulu and as far east as London. And in all instances they are Los Angeles girls." ("Coming Here For Actors," Los Angeles Times, March 24, 1912, p. III-20).

Egan Little Theatre, 1324 S. Figueroa St., 1914. Morgan, Walls and Morgan, architects. From Los Angeles Architectural Club 1913 Exhibition Catalogue.

The next year Egan moved his school and expanded his operations with the addition of the Egan's Little Theatre at 1324 S. Figueroa St. at Pico Blvd. He commissioned the venerable firm of Morgan, Walls and Morgan to design the new theatrical building and offices (see above) After brief early success as a venue for drama, Egan's theater venture fell on hard economic times and was reconfigured to also enable the screening of silent movies. ("In the Theater Foyers," Los Angeles Times, August 7, 1914, p. III-4).

"Miss Anna Zacsek Who Has Part in Egan School Play," LAH, June 19, 1914, p. 10.

Possibly her first ever publicity photo, Anna's part in an Egan School production was announced in the Herald in June 1914 (see above). By her late teens Zacsek began pursuing a Hollywood acting career in earnest. She visited the Majestic Studio in 1914-15, liked what she saw and soon became an extra. Her story as one of the more successful "extra girls" who parlayed her talents into progressively better roles was featured along with those of her D. W. Griffith-trained stablemates Mae Marsh, Seena Owens and Bessie Love in the December 1916 issue of Motion Picture Magazine (see below). The article described Anna, "She being of the foreign type, was given a place in with a mob of exotic looking supernumeraries. A few days later she was given a small part; as the days passed, her parts became better."

Zeidman, Bennie, "The Extra Girl," Motion Picture Magazine, December, 1916, pp. 45-48.

The Birth of a Nation, D. W. Griffith, 1915.

Anna's first credited part was a leading role in the 1915 release "His Lesson" soon to be followed by eleven more films during her first year. In Griffith's seminal "The Birth of a Nation," released two weeks before the opening of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, Zacsek played the role of Laura Keene whose theatrical company was playing at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C. on the night of Abraham Lincoln's assassination. After Booth, played by Raoul Walsh, leaped to the stage after shooting Lincoln in the back of the head (see above), Keene, played by Olga, rushed up to the presidential box and cradled the wounded President's head in her lap. In 1916 Griffith would also direct Zacsek in his next extravaganza "Intolerance" in which she played the part of Mary Magdelene, the original femme fatale, in the Judean portion of the film.

Intolerance, D. W. Griffith, 1916.

Babylonian movie set for D. W. Griffith's "Intolerance" at the Reliance-Majestic Studios (later Triangle-Fine Arts) site at the intersection of Hollywood and Sunset Blvds. (Author's note: The set was one block east of, and easily visible from, Olive Hill, the site of Aline Barnsdall's Hollyhock House designed by Frank Lloyd Wright with construction supervision by R. M. Schindler and Lloyd Wright.)

Zacsek reminisced (most likely through the words of a studio publicist) to a newspaper reporter in 1916 about how she was dubbed Olga Grey by Griffith and how she was tiring of being typecast as a "vamp."

"In the first place, I was engaged while a mere spectator on the side lines one day by Mr. Griffith whom we were observing as he directed some scenes for "The Clansman." When I told him my name he said, "Tut, tut! Impossible!"

As days passed I was continually cast in feature pictures and became accustomed to the work, I began to notice that my business was always to "vamp" to the total eclipse of my tender-hearted ambitions. I finally decided that this was not as it should be, and asked my director for a sympathetic part in the next production. "Impossible!" he snorted. "Heroines are always blonde. Vampires are dark. You are a vamp!" ("Olga Grey, the Griffith Vampire," by Miss Anushka Zacsek: the Hungarian Ingenue, Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger, July 8, 1916, p. 9).

Anushka Zacsek, screen name Olga Grey. Photographer unknown. "A Vamp With a Goulash Name," Photoplay, Vol. XI, No. 3, February 1917, p. 73.

Triangle-Fine Arts Studio, 4516 Sunset Blvd., 1916. From Early Hollywood by Mark Wanamaker and Robert W. Nudelman, Arcadia, 2007, p. 34.

Reliance-Majestic Studios soon evolved into the Triangle-Fine Arts Film Company (see above) and was soliciting screenplays for it's stable of young stars of which Olga Grey was prominently included. (See below for example).

"Fine Arts Film Company, 4500 Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles, Calif., is in the market for five-reel features, suitable for any of its stars: Douglas Fairbanks, Mae Marsh, Bobby Herron, Lillian Gish, Norma Talmadge, Wilfred Lucas, Fay Tinchner, Bessie Love, Olga Grey and Constance Talmadge. Often two or three of these players may appear in one picture; most of the feminine stars are ingenues, and stories in which the principal characters are young girls are therefore most desired. Stories must have underlying themes of considerable power." ("The Literary Market,"The Editor, Oct 7, 1916, p. 338).

Grey, Olga, "How I Learnt [sic] to Act," Motion Picture Magazine, December 1916, p. 69.

Ruth St. Denis, 1916. Edward Weston photograph from the Halsted Gallery. © 1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents.

Besides her role in "Intolerance" Zacsek appeared in six other films in 1916, including the role of "Lady Agnes" in Macbeth. It was around the time of Zacsek's appearance in "The Birth of a Nation" that Weston began photographing Ruth St. Denis (see above) and her dancers many of whom coincidentally appeared in the Babylonian dance sequences in Griffith's "Intolerance" under St. Denis's direction. Weston likely met St. Denis through the movie studio connections of Margrethe Mather (see below), Charlie Chaplin and costume and set designer George Hopkins (discussed later below) thus this may also be around the time that he met Zacsek. (See Stagestruck Filmmaker: D. W. Griffith and the American Theatre by David Mayer, University of Iowa Press, 2009, pp. 179-80 and Artful Lives: Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather, and the Bohemians of Los Angeles by Beth Gates Warren, Getty Publications, pp. 79-82 for more details).

Margrethe Mather and Edward Weston, Glendale, 1922. Photo by Imogen Cunningham. © 1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents.

Vivian Martin ca. 1918. Edward Weston photo. © 1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents.

Vivian Martin ca. 1918. Edward Weston photo. © 1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents.

Weston also photographed Zacsek's "The Girl at Home" co-star Vivian Martin around this time (see above) indicating the wide circle of actors then in the Weston-Mather orbit. The movie was widely released in April of 1917 (see Long Beach Palace Theater marquee below for example).

Movie poster for "The Girl at Home."

On the marquee, "The Girl at Home" starring Vivian Martin, Jack Pickford and Olga Grey. Palace Theater, 30 Pine Ave., Long Beach, H. A. Anderson, architect, 1916. Photo by G. Haven Bishop, 1917. From the online Huntington Library exhibition "Form and Landscape: Southern California Edison and the California Los Angeles Basin, 1940-1990."

Zacsek would appear in eleven additional films between 1917 and 1920 (see above for example), with a steady decline in the quantity and quality of roles likely exacerbated by factors such as aging, unwillingness to play the casting couch game and the post-war depression of 1920-21 which hit the industry hard. The ambitious Anna, seeing no future on the screen, began seeking other outlets for her acting talents and became involved in local theatrical troupes, possibly through introductions by her former teacher Frank Egan to groups such as the Drama League and the Los Angeles Civic Repertory Company where she soon became entwined within the circles of Reginald Pole (see below), Weston, and Margrethe Mather.

Reginald Pole, n.d. Photographer unknown. From I Shock Myself: The Autobiography of Beatrice Wood, edited by Lindsay Smith, Chronicle, 1985, p. 59.

Rupert Brooke, Fine Arts Building, Chicago, 1914. Eugene Hutchinson photo from The Little Review, June-July 1916, p. 33. Weston photographed Hutchinson in his Fine Arts Building studio in Chicago in 1916 through Margrethe Mather's connections with Margaret Anderson whose Little Review offices were in the same building as was Maurice Browne's Little Theatre. (See Warren, pp. 103-104).

Pole, co-founder of the Marlowe Dramatic Society with his close friend Rupert Brooke (see above) at Cambridge in 1907, had first arrived in Southern California from Tahiti in 1913 in search of a climate more suitable to his chronic asthmatic condition. Brooke had befriended countryman Maurice Browne and Arthur Davison Ficke along with Floyd Dell and numerous others in Browne's Little Theatre circle while in Chicago in 1914 around the time architect R. M. Schindler arrived from Vienna seeking employment with Frank Lloyd Wright. Brooke, Browne and his wife Ellen Van Volkenburg continued to develop a very close bond while traveling to England together in the spring of 1914. Pole also happened to be visiting his family at this time and he and Brooke briefly reconnected before Rupert was off to the War. Brooke died an untimely, tragic death due to disease he contracted while on his way to Gallipoli. A few years later Pole would name his son with Helen Taggart in honor of Rupert. (For much more on the ill-fated Brooke see Red Wine of Youth: The Life of Rupert Brooke by Arthur Stringer, Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 1948 and Recollections of Rupert Brooke by Maurice Browne, A. Greene, 1927).

In her November 1915 issue of The Little Review (see below), Margaret Anderson published a Ficke poem eulogizing Brooke accompanying the above photo and a review of his play "Lithuania" posthumously produced by Browne at his renowned Chicago Little Theatre. (To see more on Anderson and Browne and his Chicago Little Theatre circle see my "The Schindlers and Westons and the Walt Whitman School and Connections to Sarah Bixby and Paul Jordan-Smith" (WWS) and PGS). Dell also penned a sonnet on Brooke upon learning of his death in New York. (Floyd Dell: The Life and Times of an American Rebel by Douglas Clayton, Ivan R. Dee, Chicago, 1994, p. 125).

The Little Review, November 1915. (Note articles on 1925 Kings Road lecturer and life-long friend of Pauline, Maurice Browne, "Portrait of Theodore Dreiser' by Arthur Davison Ficke, "Choleric Comments" by frequent contributor Alexander S. Kaun, later Kings Road tenant, Schindler client and portrait sitter for Weston compatriot Johan Hagemeyer, "John Cowper Powys on War" by later Paul Jordan-Smith collaborator Floyd Dell's wife Margery Currey and a review of the Maurice Browne production of "Rupert Brooke's 'Lithuania' at the Little Theatre." For much more on Browne, Kaun, Weston and the Schindlers see PGS. For much more on John Cowper Powys and Paul-Jordan-Smith in Los Angeles see "The Schindlers and the Westons and the Walt Whitman School").

Recently graduated from Smith College, Sophie Pauline Gibling had just moved to Chicago and was living at Hull-House at the time the above issue of The Little Review hit the streets. Her future husband R. M. Schindler had also just returned from a six-week tour of the Panama-Pacific and Panama-California Expositions in San Francisco and San Diego, with stopovers in Los Angeles and Taos. (For more in Schindler's tour see my "Edward Weston and Mabel Dodge Luhan Remember D. H. Lawrence" and "Schindlers in Carmel, 1924"). She quickly immersed herself within the bohemian social networks of the Chicago Little Theatre and The Little Review crowd evidenced by later events in Los Angeles, some of which are discussed later below. (See also my WWS for much more on Pauline's formative years in Chicago).

The Chicago dramatic labrynth of Maurice Browne and Aline Barnsdall and the literary and dramatic circles associated with The Little Review also intermingled with the Mather-Weston-Pole circles on the West Coast as I attempt to somewhat sort out below. Having been steeped in the cauldron of the Chicago Renaissance between 1914 and 1920 it was easy for the Schindlers to thrust themselves into the radical, avant-garde and bohemian orbits of Los Angeles immediately after their arrival in December of 1920.

The Desert Inn, Palm Springs, n.d. Photographer unknown. Courtesy UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library.

While in Tahiti in 1913 awaiting a planned rendezvous with Rupert Brooke, Reginald Pole was corresponding with Robert Louis Stevenson's widow Fanny who extolled the healthful virtues of Palm Springs where she was then convalescing at the Desert Inn and Sanitarium (see above). More or less evicted by the Royal Family after an affair with a Tahitian princess before Brooke's arrival, Pole made his way from Tahiti to Los Angeles to Palm Springs where he connected with Fanny Stevenson at Nellie Coffman's Desert Inn (see above). Thus began his lifelong love affair with the desert and association with Palm Springs. (Diaries of Anais Nin: Volume 5 (1947-1955), edited by Gunther Stuhlman, Harvest, 1974 pp. 26-7).

Cumnock School of Expression ad. Los Angeles Times, September 28, 1913, p. II-1.

Cumnock School of Expression, 1500 Figueroa St., Hunt and Eager, architects, 1902. From USC Digital Archive.

Pole had to make a living so after a period of recuperation in Palm Springs he began teaching drama and directing student plays at the Cumnock School of Expression (see above) in Los Angeles around 1914-15. Martha Graham graduated from Cumnock in 1916 and began her dance studies in earnest with Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn at the Denishawn School the previous year. Graham also starred as Katherine at the late 1916 Cumnock School production of Shakespeare's "Taming of the Shrew" under Pole's direction (see below). (For more on this do a "Graham" search in my "Bertha Wardell Dances in Silence").

"Girls in Masculine Roles to Play 'Taming of the Shrew," LAH, December 8, 1916.

Not long after joining the Denishawn troupe Graham was captured in a Spanish interpretation by Denishaw Studio muralist Eduard Buk Ulreich (see below). Around the same time the eagerly ambitious Graham was cast in Gilmor Brown's first ever Pasadena Players production of "The Song of Lady Lotus Eyes." Graham was also honored with the first stage entrance in the November 20, 1917 Shakespeare Clubhouse performance which almost certainly would have had Japanophile Ramiel McGehee in attendance. ("The Growth of a Little Theater," California Arts and Architecture, November 1937, p. 9).

Eduard Buk Ulreich painting of Martha Graham, "Art Calendar," California Arts and Architecture, March 1937, p. 6.

Helen Taggart, date and photographer unknown. From Ancestry.com.

The Shakespearean thespian Pole met his soon-to-be wife Helen Taggart (see above), daughter of a future client of Frank Lloyd Wright, Jr., aka Lloyd Wright, either at the English Tudor-style Cumnock School where she had been a student or during rehearsals for performances of the Drama League and/or the Los Angeles Civic Repertory Company. Taggart's first publicized appearance was for her part in "The Patriots" by Florence Haines-Reed staged May 1, 1915 by the CRC at the Gamut Club (see below). ("Patriotism or Murder; Gamut Club Audience Applauds Strong Playlet by Local Woman Attacking the Theory of War," Los Angeles Times, May 2, 1915, p. II-2).

Gamut Club, 1044 S. Hope St. (former home of the Dobinson School of Expression and Dramatic Art) 1903, Abram M. Edelman, architect. Photo taken in 1926 courtesy of LA Public Library Photo Collection.

In his review of the CRC Gamut Club productions in the California Outlook, then head of the USC School of Journalism Bruce Bliven wrote,

"If the company can continue to choose, mount and cast its plays as well as it did in these performances, its success is assured; not in a long time has anything been done, by amateurs or professionals, in this city which has been so artistically satisfying." (Bliven, Bruce, "Good Plays by Good Amateurs," California Outlook, May 22, 1915, pp. 9-10).

A week after Taggart's Gamut Club appearance the Cumnock School staged a Vaudeville show and the Times review listed performances by her and the multi-talented Martha Graham (see below) who would also begin begin studying with Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn before graduating from Cumnock the following year. ("Comedy Their Specialty; Dramatic Students Stage a Vaudeville Show," Los Angeles Times, May 8, 1915, p. II-3. For much more on Graham see my "Schindlers-Westons-Kashevaroff-Cage").

"Dances to Feature May Day Fete in L.A.," LAH, April 27, 1915, p. 1

Martha Graham in her Denishawn debut as Priestess of Isis in A Dance Pageant of Greece, Egypt and India, 1915. From Martha Graham: A Dancer’s Life by Russell Freedman, Clarion Books, 1998, p. 30.

Original Al Malaikah Temple aka. Shrine Auditorium, 1907-1920, corrner of Royal St. and Jefferson Blvd., Jefferson Blvd. entrance, ca. 1915. Photographer unknown. Courtesy USC Digital Photo Collection.

Shortly after enrolling with Denishawn, Graham was drafted along with 100 other classmates to perform with Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn (see below) in an ancient civilization-themed extravaganza at the Shrine Auditorium (see above) a week after the release of "Intolerance" and a month before rehearsals began for the inaugural performance of Aline Barnsdall's Los Angeles Little Theatre discussed later below. St. Denis was featured in the roles of Queen of Ethiopia, God Isis, Persephone and Parvati. Thus it is possible that Graham could have also danced with the St. Denis troupe in the Babylonian sequence of "Intolerance" filmed just a month or two earlier, or at least witnessed or was inspired by the company being filmed. ("Dancing Pageant to Depict Egypt; Ancient Civilizattion As Spectacle's Theme," Los Angeles Times, September 14, 1916, p. II-2). (Author's note: Graham refused to pose for Weston while his friend and patron Merle Armitage was preparing a book in her honor during 1935-6. Weston's biographer Ben Maddow speculated that she may have been afraid that Weston would want to photograph her nude. Edward Weston: His Life, p. 210).

Ted Shawn Christmas card, 1915. Photograph by Edward Weston, 1915. Courtesy of New York Public Library Digital Gallery.

"Eagle Rock Is To Stage Shakespeare," LAH, July 7, 1915, p. 4.

Two months later in another CRC production of Shakespeare's "A Midsummer Night's Dream" directed by Pole in Eagle Rock Park, Taggart played Hermia (see above) and Pole, besides directing, ironically played Demetrius presaging his soon-to-be marriage to Helen. This major outdoor spectacle staged for an evening audience of 10,000 in the natural amphitheater at the base of Eagle Rock also featured Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn's fairy ballet (including Martha Graham) and a giant orchestra. ("Enchantment Holds Sway: "Midsummer Dream" in Garden of Sycamores," Los Angeles Times, July 10, 1915, p. II-6 and "Midsummer Night's Dream at Eagle Rock, Santa Monica Bay Outlook, June 30 1915, p. 7. For much more on St. Denis, Shawn and Graham see my "Bertha Wardell Dances in Silence").

"Wins L.A. Society Girl in Dash Half Way Across the U.S.," LAH, September, 27, 1916, p. 1.

The marriage of Pole and Taggart took place in Chicago the following summer. The fascinating love story of the handsome couple was featured above-the-fold on the front page of the Herald (see above and below). Helen and her mother Martha had gone to Chicago for a lengthy visit with relatives.

"Mr. Pole, learning that she expected to remain some time, started at once for Chicago, telegraphing her en route that he would join her in Chicago and urging an immediate marriage. She received his telegram on September 10, wired her consent and the two were married at St. Paul’s church at noon on September 12. Their marriage was followed by a smart wedding breakfast at the South Side Country club and a honeymoon First to the woods on Lake Michigan and later with a camping trip at the bottom of the Grand canyon.

The marriage was the result of a romance which began In Los Angeles two years ago when Mr. Pole staged an amateur production of "Midsummer Night’s Dream,” In which Miss Taggart, prominent in amateur theatrical circles, played a part. Under his direction Mrs. Pole will continue her dramatic work now. The young couple are at home to their friends at 2310 Scharff Street, where they will make their permanent residence." (Ibid).

Greek Theater, Pomona College, Claremont, ca. 1922. Myron Hunt, architect, 1914. Photographer unknown. From the Pomona Library Digital Images Collection.

In 1916 Pole landed the position of Pomona College drama director and produced student performances of Shakespeare and Greek drama in the campus's recently completed Greek Theater (see above). (Ford, Sydney, "Opening of Pomona College," The Pacific, Oct 5, 1916, p. 6). The venue was a perfect fit for the Elizabethan-trained Pole whose uncle William Poel (see below) founded London's Elizabethan Stage Society which held performances free of scenery and modern staging to simulate the theatrical conditions under which Shakespeare's plays were originally performed.

William Poel as Adonai (God) in an Elizabethan Stage Society production of Everyman, 1901. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum.

In late 1916, uncle William visited Reginald in Los Angeles, who was by then living with Helen, and was feted along with Aline Barnsdall's Los Angeles Little Theatre director Richard Ordynski by the Drama League. Both Poel and Ordynski were questioned during interviews what they thought of Griffith's "Intolerance" and both deferred to Griffith. ("Two are Honored by the Drama League," Los Angeles Times, November 12, 1916, p. II-1 and "This Is Day for American Drama; Noted British Critic Here With Comment," Los Angeles Times, November 6, 1916, p. II-5).

During 1916, the seemingly indefatigable Pole divided his time between Pomona College, Cumnock School and other various troupes and productions in and around Los Angeles. This year also marked the tricentennial of William Shakespeare's death which was honored by Griffith's earlier-mentioned production of "Macbeth" featuring Zacsek as Lady Agnes. During April and May there were numerous Shakespearean productions in the Los Angeles area. For example Reginald Pole starred in a scene from "Twelfth Night" staged by the Galpin Shakespeare Club at their Cumnock School headquarters and again played the king in act five from "Richard the Second" at the Hollywood Woman's Club (see below). ("In Remembrance of the Great English Bard," Los Angeles Times, April 16, 1916, p. II-13).

Woman's Club of Hollywood, 7078 Hollywood Blvd. between Sycamore Ave. and La Brea Ave. From "Woman's Club of Hollywood," Holly Leaves, July 1, 1922, p. 18. Photo by Viroque Baker, Schindler friend and soon-to-be photographer and client. (See "The Schindlers and the Hollywood Art Association").

Inspired by the work of Maurice Browne and Ellen Van Volkenburg at their Chicago Little Theatre, wealthy oil heiress Aline Barnsdall in 1915 begun discussing with Frank Lloyd Wright plans for a new, larger Chicago theater envisioned to be under their directorship. After summering in California and visiting the state's Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco Barnsdall's plans changed. She moved to San Francisco in 1916 and at first decided to open her theater there while Browne and Van Volkenburg opted to stay in Chicago. (For much more on Browne and Van Volkenburg see my "Pauline Gibling Schindler: Vagabond Agent for Modernism" and "Schindlers-Westons-Kashevaroff-Cage").

Coincidentally, Frank Lloyd Wright had also visited the Panama-California Exposition and its prominently displayed models and photos of Uxmal and Chichen Itza (see below) through he which he was likely imbued with Mayan inspiration for the later design of Barnsdall's Olive Hill complex. (See for example Frank Lloyd Wright: The Lost Years, 1910-1922 by Anthony Alofsin, University of Chicago Press, 1993, p.225 and Frank Lloyd Wright: A Life by Ada Louise Huxtable, Penguin, 2004, p. 157).

Carlos Vierra, fresco of Chichen Itza, Panama-California Exposition, 1915. From Alofsin, p. 228. Originally in Art and Archaeology 2, 1915.

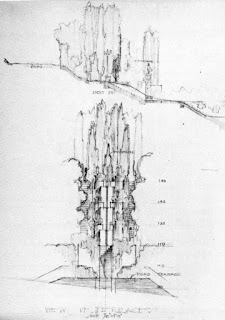

Hollyhock House, perspective view, Los Angeles, 1917-20. Alofsin, p. 236.

Model, "The Palace," Uxmal, Panama-California Exposition, 1915. From Alofsin, p. 229. Originally in Art and Archaeology 2, 1915.

Mary Austin, front center, rehearsing the cast of "Fire" for a 1913 performance at Carmel's Forest Theatre. Herbert Heron played the lead role of Evind, the fire bringer. George Sterling as Atla the hunter, upper right. From Old Carmel in Rare Photographs by L. S. Levin produced by Sharon Lawrence with Kathryn Prine, Carmel, 1995, p. 29.

While in San Francisco, Barnsdall wrote to erstwhile Carmel playwright and author Mary Austin about the possibilities of opening an outdoor theater there, likely having heard of her earlier exploits at the seaside village's Forest Theater (see above for example). (For much more on Austin, Maurice Browne and the Forest Theater see my Schindlers-Westons-Kashevaroff-Cage (hereinafter SWKC), "The Schindlers in Carmel, 1924" and PGS).

Encouraged by what she heard Barnsdall visited Carmel in May and met with Forest Theater director Herbert Heron (see below). She soon responded to Austin that she needed a larger city for her vision to succeed. (Barnsdall Letters to Mary Hunter Austin, Mary Hunter Austin Collection, Huntington Library, cited in Friedman, pp. 34-37). Barnsdall did, however, entice Heron to sign an eight-month, $50.00 per week contract to join her growing troupe upon the completion of his Forest Theatre summer season. (Letter from Herbert Heron to Will , Heron Papers, Harrison Memorial Library, Carmel).

Herbert Heron, director, Forest Theatre, Carmel. Courtesy Carmel Harrison Memorial Library.

Program for "Julius Caesar" courtesy of the Hollywood Bowl Museum.

Barnsdall was likely lured south to Los Angeles by the obvious opportunities presented by the burgeoning Hollywood scene evidenced by the May 19, 1916 extravaganza "Julius Caesar" celebrating the 300th anniversary of Shakespeare's death. The production starred the likes of Douglas Fairbanks and Tyrone Power and was staged in the 40-acre natural outdoor amphitheater in Beachwood Canyon. An audience of over 40,000 witnessed the one-night-only performance which included 5,000 performers and dancers and hundreds of students from nearby Hollywood and Fairfax High Schools. Tyrone Power starred as Marcus Brutus and Douglas Fairbanks as Young Cato. Other stars included William Farnum as Cassius, DeWolf Hopper as Casca and Mae Murray. The Battle of Philippi was re-created on a monumental stage constructed on the future site of Beachwood Village (see below).

"Julius Caesar" set on the site of what would become Beachwood Village. Courtesy of Library of Congress. (See also the excellent When Shakespeare Came to Beachwood Canyon: “Julius Caesar,” 1916).

"Los Angeles to Outdo World in Tribute to Bard of Avon," Los Angeles Times, April 16, 1916, p. II-1.

Egan School of Music and Drama and Little Theatre, 1324 S. Figueroa St., 1914. Morgan, Walls and Morgan, architects. From Year Book, Los Angeles Architectural Club, Fourth Exhibition, Under the Auspices of the Architectural League of the Pacific Coast, 1913.

Through her Players Producing Company Barnsdall took out a six-month lease on Frank Egan's earlier-mentioned Little Theatre (see above) and renamed it the Los Angeles Little Theatre and engaged Norman-Bel Geddes to design the sets and signed Richard Ordynski to a ten-week contract to direct the plays. (Miracle in the Evening by Norman Bel Geddes, Doubleday, New York, 1960, pp. 152-170 and Frank Lloyd Wright: Hollyhock House and Olive Hill by Kathryn Smith, Rizzoli, 1992, pp. 15-37).

Players Producing Co. 1916-17 Season program designed by Norman Bel-Geddes.

Also moving to Los Angeles to take part were some Ordynski recruits from New York including Irving Pichel and Gareth Hughes, and some alumni from Maurice Browne's Little Theatre in Chicago including Elaine Hyman, later stage name Kirah Markham, a former lover of Floyd Dell and Theodore Dreiser. Frayne Williams (see below), an old friend of Charlie Chaplin's from their Vaudeville days in England, also accompanied Ordynski to Los Angeles and soon hooked up with the Mather-Weston circle and reconnected with Chaplin. (Warren, p. 121).

Frayne Williams as Hamlet, 1918. Margrethe Mather photo. From Margrethe Mather & Edward Weston: A Passionate Collaboration by Beth Gates Warren, Norton, 2001, p. 49.

Kirah Markham in "Nju." "Little Theater Opening Is To Be Feature of Week," Los Angeles Times, October 29, 1916, p. III-1.

A May 1917 article in The Little Theatre Magazine summed up Barnsdall's 10-week, seven-play season and outlined the roles played by Ordynski, Geddes, Kirah Markham, Frayne Williams, Herbert Heron, Irving Pichel and many others. Frayne Williams directed and played the lead role in "A Farewell Supper" by Arthur Schnitzler. Besides starring in Barnsdall's opening production of Ossip Dymow's "Nju" alongside Anna Andrews (see below), Markham had the lead role in Chicago playwright Oren Taft's "Conscience" which Barnsdall had staged the previous year in the Fine Arts Theater in Chicago also starring Markham, and the world premiere of D. H. Lawrence's "The Widowing of Mrs. Holyroyd," both under Pichel's direction. Former Carmel luminary George Sterling's translation of Hugo von Hofmannsthal's version of "Everyman," in collaboration with Ordynski, was the grand finale of Barnsdall's season. (Dare, Ann, "The Little Theatre of Los Angeles, The Little Theatre Magazine, May 1917, p. 5. The Oilman's Daughte: A Biography of Aline Barnsdall by Norman M. and Dorothy K. Karasick, Carleston Publishing, 1993, pp. 50-53, and Warren, p. 121). (Author's note: For much more on D. H. Lawrence see my "Edward Weston and Mabel Dodge Luhan Remember D. H. Lawrence").

Nju, (Miss Anna Andrews) by Max Wieczorek, 1917. From Max Wieczorek: His Life and Work by Everett Carroll Maxwell, Los Angeles, 1930, p. 65.

Barnsdall and the bisexual Ordynski had a brief, turbulent affair in November 1916 which resulted in Aline becoming pregnant. The couple had a falling out after Aline's condition became known prompting Ordynski to resign from the company after only two plays and apparently begin a relationship with George Hopkins. Barnsdall carried on with substitute directors Frayne Williams, Herbert Heron, and Irving Pichel who ably filled in for Ordynski for the season's remaining four plays including Schnitztler's "Anatol" in which Williams played the leading role (see below).

Frayne Williams as Anatole, ca. 1920. Photo by Margrethe Mather. From Warren, p. 200. Courtesy J. Paul Getty Museum, 86.XM.721.3.

Trinity Auditorium, 855 S. Grand Ave. ca. 1920. Thornton Fitzhugh, Frank G. Krucker and Harry C. Deckbar, architects, 1914. LAPL.

Likely after learning of Hopkins' considerable costume and set designing skills, Ordynski came up with the idea to produce a modern day version of "Everyman" imitating his former colleague Max Reinhardt's earlier Berlin productions. (Kingsley, Grace, "'Everyman' To Be Presented in Up-To-Date Version," Los Angeles Times, December 21, 1916, p. II-6). He also likely discussed his plans with Reginald Pole's uncle William Poel during their mid-November reunion mentioned earlier above. Despite their acrimonious breakup, Ordynski was able to convince Barnsdall to finance his grandiloquent production and stage it at the 3,000 seat Trinity Auditorium (see above). After committing to finance Ordynski's production Barnsdall was quoted, "Whatever is worth doing along this line is worth doing well. No expense should be spared to make the play as perfect as possible." ("More Big Things May Follow," Los Angeles Times, December 24, 1916, p. III-17).

George Hopkins, 1915. (see Warren, p. 79). Photo by Edward Weston. Johan Hagemeyer Collection. © 1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents.

The well-reviewed Barnsdall-Ordynski "Everyman" production starred a late recruit from New York, Gareth Hughes as Everyman, Kirah Markham as Everyman's mother, Irving Pichel, and Frayne Williams. George Hopkins (see above) received much praise for his stage sets and costumes (see below). ("Ordynski "Everyman" Production at Trinity Promises to Unveil New Vista in Esthetics of the Stage - Brilliant is the Conception of Play," Los Angeles Times, December 31, 1916, p. III-11). The production was undoubtedly followed with great interest by Reginald Pole. Weston photographed Hopkins the year before and was also hired by him to photograph his creations modeled by dancers Maud Allan and Violet Romer (see two below) as well as Yvonne Sinnard, Katharane Edson, and Margaret Loomis, then dance students of Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn. (For much more on Ordynski, Barnsdall and the Schindlers see my "Pauline Gibling Schindler: Vagabond Agent for Modernism" (PGS)).

"Modern In Its Art; Ordynski Everyman Production at Trinity Promises to Unveil New Vista in Esthetics of the Stage - Brilliant is the Conception of the Play," Los Angeles Times, December 31, 1916, p. III-11.

Violet Romer (as a Peacock by a Pool), ca. 1916. Photography by Edward Weston at the Anita Baldwin McClaughrey estate "Anoakia. Costume likely by George Hopkins. From Warren, p. 80. Courtesy of The Huntington Library, 000.111.505.

Anita Baldwin McClaughrey estate "Anoakia," Arcadia, Arthur B. Benton, architect, 1913. Photo dated July 25, 1915 from the LA Public Library Photo Collection. (Author's note: McClaughrey commissioned later Weston-Schindler compatriot Dorothea Lange's husband Maynard Dixon to decorate her "Indian Room" with a continuous frieze depicting scenes from the northern plains. "Unique Among Homes of America's Rich," Los Angeles Times, September 21, 1913, p. II-7. Dixon attributed this commission as a major turning point in his career. Architect Benton also designed Sarah Bixby Smith's "Erewhon" and the Friday Morning Club).

Knowing of his father's work for Barnsdall, especially for her theater, Lloyd Wright followed the progress of her Little Theatre productions, especially since he was also at the time designing sets for Cecil B. DeMille's and Frank A. Garbutt's Paramount Pictures. This most likely brought him into contact with Barnsdall's set designers Geddes and Hopkins. (Gebhard, p. 22. For more on Lloyd Wright's introduction to Garbutt and De Mille see my "Irving Gill, Homer Laughlin and the Beginnings of Los Angeles Modern Architecture, Part II, 1911-1916" hereinafter "Gill-Laughlin)).

Lloyd kept his father up to date on Barnsdall's activities by letter. He also soon became starstruck by the captivating Kirah Markham whom he may have met during his brief return to Chicago in late 1913 and early 1914 implied in the below October letter. ("Gill-Laughlin: Part II")

"Dear Father

I am enclosing a photograph of one of my gardens. Nothing remarkable about it but it is the first one I have yet had taken and thought you might be interested. The spot was a rocky slope 18 months ago. But really what I have written you for was to tell you that I am to marry Kira, Kira Markham, Elaine Hieman [sic] you know, the 8th of this month or thereabouts. What do you think of it I should much like to know. I am doing the rash thing of course and dead broke at this moment and living on nerve. But that seems to be the scheme as it works out. Write me before the eighth. I should like to hear from you.

Son Lloyd" (LW to FLW,. n.d. ca. October 1916. Frank Lloyd Wright Letters, Getty Research Institute).

After an extremely brief courtship the couple were married on November 18th. The ceremony was witnessed by Mott Montgomery, a mutual architect friend of Lloyd and Barry Byrne whom they met in 1913. For much more on this see my "Irving Gill, Homer Laughlin and the Beginnings of Modern Architecture in Los Angeles: Part II" (Gill-Laughlin, Part II)). The ambitious Markham was likely attracted to the connections Lloyd was privy to at Paramount and also later claimed she was seduced by the fame and architecture of his larger-than-life father. (Theodore Dreiser: Letters to Women; New Letters, Volume II edited by Thomas P. Riggio, University of Illinois Press, 2009, p. 119, note 2). Around the time Markham began rehearsals for "Everyman" she was already reporting back to Dreiser on the difficulties with her marriage. (Dreiser letter to Markham, December 14, 1916, Riggio "Letters," pp. 118-19.

Kirah Markham, from the W. A. Swanberg Papers, Penn Libraries, Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Clarence McGehee portrait with announcement of upcoming Cherry Blossom Players productions, Los Angeles Times, December 31, 1916, p. II-10.

"Cherry Blossom Players to Give Performances Soon," Los Angeles Times, January 14, 1917, p. III-19.

After a two-year association with Ruth St. Denis helping her develop her Japanese dance routines, Japanophile McGehee supported himself translating and lecturing on Chinese and Japanese topics and and producing and performing Japanese dance routines before a wide range of organizations and women's clubs. By 1916 he had become involved with a Japanese theatrical troupe called the Cherry Blossom Players (see articles above) for which he directed drama and dance productions under his friend Norma Gould's business manager and impresario Lyndon E. Behymer.

McGehee's contagious enthusiasm for the Cherry Blossom Players likely helped him convince impresario Behymer that being able to advertise set designs by the son of the noted architect and fellow Japanophile Frank Lloyd Wright would help in attracting a wider audience to their Japanese troupe's performances at the Alexandria Hotel (see below) in January 1917. Frank Lloyd Wright, Jr. (aka Lloyd Wright) was by this time designing stage sets for Paramount Pictures through the largess of architect William J. Dodd's connections with Cecil B. De Mille and Frank Garbutt. Lloyd and McGehee had likely crossed paths at the Los Angeles School of Art and Design's Palette Club meetings where Wright lectured on landscape architecture in April 1915 and McGehee on Japanese prints, dance and folklore in February 1916. (For much more on McGehee and Ruth St. Denis and Lloyd Wright see my "Bertha Wardell: Dances in Silence: Kings Road, Olive Hill and Carmel").

Alexandria Hotel, 501 S. Spring St.,ca. 1920s. John Parkinson, architect, 1906, 1911 addition. From Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

Chicago Examiner, May 17, 1911, p. 9.

The precocious Markham, then Elaine Hyman, studied drama at the Art Institute of Chicago ca. 1911-12 where she staged a play she had written, "The Master Painter." ("Girl Art Students Show Dramatic Genius; Life Class Stages Tragesy and 'Thriller'," Chicago Examiner, May 17, 1911, p. 9). She soon appeared as Andromache (see below) in Maurice Browne's first staging of Euripedes' "The Trojan Women" at his Chicago Little Theatre in 1913 where she likely first drew Aline Barnsdall's attention. It was also during this performance that Floyd Dell, then married to suffragist Margery Currey, became entranced with her and began an affair. Then in Chicago working on The Titan, the legendarily lecherous Theodore Dreiser who had accompanied Dell to the opening of "The Trojan Women," was also mesmerized by Markham and was able to lure her affections away from Dell. Dreiser left for New York a few months later and was soon joined by Markham on occasion as her Little Theatre touring schedule permitted. (Author's note: It was during this time that Paul Jordan-Smith, then in graduate school at the University of Chicago, became intertwined in the bohemian circles of Maurice Browne, Floyd Dell, John Cowper Powys and Arthur Davison Ficke thus he likely knew Markham as well. For more on this see my "WWS").

Kirah Markham as Andromache in Euripedes' "The Trojan Women," at Maurice Browne's Chicago Little Theatre, 1913. (Riggio, "Letters," p. 81).

Theodore Dreiser in his Greenwich Village apartment at 165 W. 10th St. in the late 1910s. In Chicago Dell wrote influential reviews commending Dreiser's early novels. Dreiser later praised Dell's first novel, Moon-Calf. From Floyd Dell: The Life of an American Rebel by Douglas Clayton, Ivan R. Dee, 1994, p. 144. Courtesy Theodore Dreiser Papers, Penn Libraries, Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Kirah Markham ca. 1912. Photo by Jessee Tarbox Beals. From Archives of American Art.

Despite being utterly dismayed by being jilted by Markham and having by then left his wife Margery Currey, Dell visited Markham and Dreiser later that summer and became reconciled to the fact that she preferred the older, wiser, more established man. After also visiting Provincetown and finding the bohemian lifestyle much to his liking, Dell too decided to move to New York. The next year Markham moved in with Dreiser in Greenwich Village on a more or less permanent basis. She would soon be performing in plays written by Dell at Greenwich Village's Liberal Club and the Provincetown Players in Cape Cod and later at their New York Playhouse until leaving Dreiser in the summer of 1916 to join Barnsdall's Little Theatre troupe in Los Angeles.

Lloyd Wright, ca. 1920. From "The Blessing and the Curse" by Thomas S. Hines in Lloyd Wright: The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, Jr. edited by Alan Weintraub, Abrams, 1998, p. 14.

In an undated letter ca. 1916 Lloyd Wright reached out to his father with an invitation to visit him,

"...so that I might show you what I am doing and so that we might have an outing together. I am now in shape to entertain rather than be entertained as previously. Have just become a member of the Sierra Madre Club (see below) and am slowly establishing myself in the life of this city. Have just written a little one-act sketch called 'Manikin' ... with an opportunity for good dancing, music, and stage sets. My real work is progressing to a point where worry is finding little chance to play its part. ... Pretty good considering that I started here without capital, name, or a very wide experience." (LW to FLW, n.d.. Frank Lloyd Wright Correspondence, Getty Research Institute. Also cited in Hines, p. 15. See also "Gill-Laughlin: Part II").

"Sierra Madre Club, New Quarters," Los Angeles Mining Review, March 8, 1913, p. 1. Los Angeles Investment Company Building, Eight St. and Broadway, Austin and Pennell, architects.

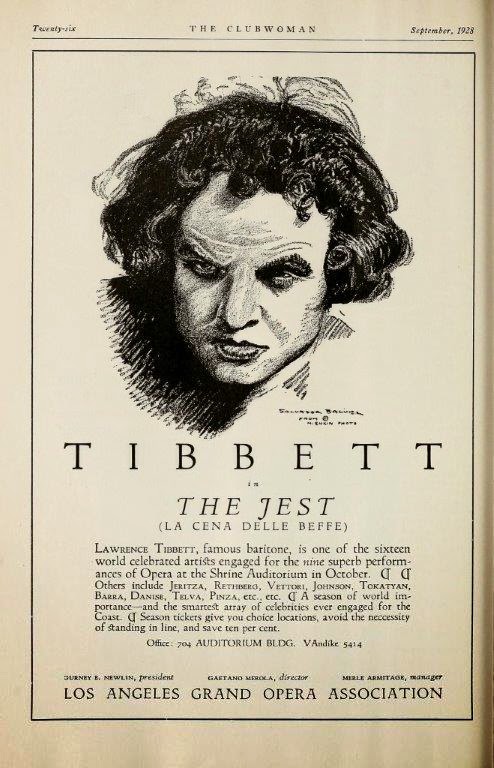

Lloyd's mention of his "Manikin" sketch possibly places him within the Mather-Weston circle as early as this period as Alfred Kreymborg, whose play "Manikin and Minikin" was staged at the Hollywood Community Theatre in February of 1918 starring Lloyd's and Reginald Pole's lifelong friend Lawrence Tibbett and Carlotta Rydman. On the same bill Tibbett (see below) also played the lead role in Earnest Dowson's "Pierrot of the Minute." (Warnack, Henry Christeen, "Players Popular," Los Angeles Times, February 22, 1918, p. II-3).

Lawrence Tibbett (Mercutio) as he appeared in the 1914 program for Maunual Art High School's production of Romeo and Juliette. Photographer unknown. (Dear Rogue: A Biography of the American Baritone Lawrence Tibbett by Hertzel Weinstat and Bert Wechsler, Amadeus Press, Portland, OR 1916, p. 144).

Tibbett's close friend Arthur Millier, later to become an etcher of note and in 1926, the art critic for the Los Angeles Times, was also a habitue of the Pole-Lloyd Wright circle. Millier played the role of Jacques in the 1911 Los Angeles High School dramatic class production of Shakespeare's "As You Like It." ("In the Public Schools," Los Angeles Times, January 15, 1911, p. II-7). This presaged Millier's gravitational attraction into the orbit of Shakespearean director Pole evidenced by him and Pole serving as witnesses at the May 19, 1919 marriage of Tibbett to his first wife Grace. (Dear Rogue: A Biography of the American Baritone Lawrence Tibbett by Hertzel Weinstat and Bert Wechsler, Amadeus Press, Portland, OR 1916, pp. 37-38).

Kreymborg first visited Los Angeles in the summer of 1917 to read his poetry at the Friday Morning Club and promote his latest literary journal Others. (Troubadour: An Autobiography by Alfred Kreymborg, New York, 1925). During the trip he also visited Mather's studio, likely at the suggestion of friend and former Little Review employee and contributor William Saphier. Saphier had a brief fling with, and had his portrait taken by Mather who also exhibited same a few months later. (Anderson, Antony, "Of Art and Artists," Los Angeles Times, May 27, 1917. Also see Warren, p. 118. For much more on Kreymborg and Saphier see my "Bertha Wardell: Dances in Silence").

Gaining ever more confidence with his Los Angeles surroundings and expanding dramatic circle Lloyd proposed to his father that they form a partnership and enjoy the finer things that the burgeoning city had to offer.

"I often wish that you might be able to free yourself from the various loads you seem to enjoy piling upon your back and that we two could enter the field together as father and son. I believe we could make them all sit up and enjoy us, and we'd have a glorious time doing it. Architecture, landscape architecture, the theater, and music with the various luxuries and interesting diversions that attach thereto. And do it in a gloriously fine way too. If I only had your sincere support in the matter, I could rip the very devil out of his hole." (LW to FLW, Frank Lloyd Wright Correspondence, Getty Research Institute. Also cited in Hines, p. 15. See also("Gill-Laughlin: Part II").

Although the two Wrights never established a permanent partnership, they would work together on a rather large number of projects between 1922 and 1924, some also with Schindler's minor involvement, as Lloyd and RMS gradually developed remarkable, totally independent (from FLW) careers after Wright returned to Taliesin in early 1924.

In a letter sometime after his father sailed for Japan with Miriam Noel to begin work on the Imperial Hotel on December 28, 1916 shortly after his impulsive November wedding, Lloyd (see above) presciently described his new bride as,

"... an independent. In spite of it, however, a wife. We have taken an old shack (see below) in an acre of acacia and [are] decorating the house on next to nothing. Kira is restless, ambitious and forceful, a good thing for us both. She is, however, prone to, or rather impressed by, the fact that the successful stage careers of today (the majority of them) are made by the 'successees' selling their bodies and their souls to the 'successors.' Perhaps she will get over it. I hope so." (LW to FLW, n.d. Hines, p. 15).

During her time as part of Aline Barnsdall's Los Angeles Little Theatre troupe Markham was living at 1628 Argyle Ave. right around the corner from Hollywood and Vine. The 1917 Directory listed Lloyd (and Markham) living at 1639 [sic-1936] Pinehurst Rd. in Hollywood (see above) from where

Kirah shared her opinion of Barnsdall with her new father-in-law,

"[She] really has no actual conception of what she wants to do with a theatre at all. She has vague illuminated moments, but the flashes that come in are eternally slipping away on close contact she puts in power to execute them....And she wants so much to go on. Yet I scarcely believe I could endure the strain of a second season with her." (Kirah Markham, 1936 Pinehurst Rd., Hollywood to FLW, Taliesin, February 7, 1917, FLW Archives, Taliesin West cited in Frank Lloyd Wright: Hollyhock House and Olive Hill by Kathryn Smith, Rizzoli, 1992, pp. 22-3).

Kirah also reported her impressions of the elder Wright in one of her frequent letters to Dreiser. Dreiser responded,

"Dearest Cryhon:It was fine to get your letter, which just came here - along with one from Mautice Browne. I'm up here working in the woods and had not intended to return to New york before Aug. 1, but I may get there earlier. Of course I'll see you. Did you get my letter about my conversation with Browne - a month or so ago. He wanted you to come back to him. Said he would pay as much as the Washington Square Players & would feature you. If you haven't seen him do. What a picture you paint of your father-in-law. I should like to meet him sometime..." (Letter from Dreiser to Markham, July 3, 1917, Riggio "Letters," pp. 127-8).

Possibly on Dreiser's advice Kirah and Lloyd moved back to Chicago in late summer or fall of 1917 where Lloyd designed a landscape for the Mrs. S. M. B. Hunt House in Oshkosh, Wisconsin while Kirah was reconnecting with Browne and Van Volkenburg about the time their Chicago Little Theatre in the Fine Arts Building was folding up its tent for good.

Markham eagerly wanted to return to Greenwich Village to be among her transplanted Chicago friends and have a better chance for work. As his young practice had yet to gather steam and still wishing to make the marriage work, Lloyd agreed to accompany her. They were in New York by December per Dreiser's diary. Once back in New York Kirah happily reconnected with Dell and Dreiser and the Washington Square Players, Provincetown Players and Playhouse crowds while Lloyd worked a series of day jobs including Standard Aircraft, Curtis Aircraft and the architectural firm of Rouse and Goldberg. (Lloyd Wright, Architect: 20th Century Architecture in an Organic Exhibition edited by David Gebhard and Harriette Von Breton, Art Galleries, University of California, Santa Barbara, 1971, pp. 22-23).

In his spare time Lloyd designed stage sets for at least one of the Provincetown Players' productions, "The String of the Samisen" (see playbill below).

"The Provincetown Players Fifth Season 1918-1919," p. 3. From The Provincetown Players and the Playwright's Theatre, 1915-1922 by Edna Kenton, McFarland, 2004, p. 92. Courtesy Scheaffer-O'Neill Collection at Connecticut College.

Dreiser wrote of his first get together with Markham after her return,

"Kirah calls up. Is at 7 Fifth Avenue. Wants me to come over. Go. She is downstairs when I get there. Haven't seen her in over a year, when we lived together. Cries and hugs me. Tells me of her life in Los Angeles as star of Little Theatre. The attitude of [Richard] Ordynski the director toward her. Played two leading roles. Didn't like her because she wasn't his style of beauty. Now is Mrs. Frank Lloyd Wright, Jr. Character of her father-in-law, the architect. His opposition to her because he thought she wanted to return to me. Her father also in opposition-same reason. Wright's great estate in Wisconsin. His mistress. Housekeeper steals letters and publishes them. He takes his discarded mistress back. Kirah wants me to meet her occasionally when she is with her husband and pretend not to have seen her before. I leave, agreeing to meet her somewhere soon." (Riggio, "Diaries," pp. 170-1).

Markham remained in periodic contact with Dreiser but always without Lloyd. Oddly, she seemed uncomfortable introducing him to her former lover. They apparently did not socialize together as Dreiser's December 6, 1917 diary entry mentioned awkwardly encountering Markham and Wright in a cafe and saying of him "He looks very interesting." (Riggio "Diaries," p. 230. Author's note: Dreiser would finally meet Wright at his Taggart House in the summer of 1922 as discussed later herein.).

As Dreiser's frequent 1917-18 correspondence with Markham and diary entries indicate, the Wright-Markham marriage was indeed turbulent and fraught with separations brought on by Kirah's growing boredom with Lloyd and lack of work. (Riggio, "Letters," and Theodore Dreiser: American Diaries, 1902-1926 edited by Thomas P. Riggio, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982). Kirah and Lloyd did however visit the elder Wright at Taliesin for six weeks in the late spring of 1918 after his recent return from Tokyo where he had begun work on the Imperial Hotel project. (Hines p. 16)

From left, William E. Smith, R. M. Schindler, Arato Endo, Goichi Fujikura, and Julius Floto, consulting engineer on the Imperial Hotel, at Taliesin, spring 1918. From Frank Lloyd Wright: Hollyhock House and Olive Hill by Kathryn Smith, Rizzoli, 1992, p. 20.

Meanwhile, trying to find work with Lloyd's father while working for Ottenheimer, Stern and Reichert since his 1914 arrival in Chicago from Vienna, R. M. Schindler was finally able to move into Taliesin (see above) in February 1918 and immediately began working on the Imperial Hotel and Barnsdall theater and residence projects. Schindler most certainly met Lloyd during his and Kirah's lengthy spring 1918 Taliesin stopover before they returned to New York where they hoped to save their shaky marriage and establish careers.

After FLW sailed for Japan that fall, Schindler and Will Smith moved into Wright's Oak Park Studio. Soon afterwards, Schindler met Sophie Pauline Gibling (see below) and married her the following summer. Coincidentally and unbeknownst to Lloyd, by helping his father put together his famous Wasmuth Portfolio in Italy in 1909-10 (see below) which was published in Germany the following year, he played a small part in attracting R. M. Schindler (and later Richard Neutra) to America to work for their mutual idol. (For more on this see my "Chats").

Lloyd Wright photo of Taylor Woolley at Villino Belvedere, Fiesole, Italy, 1910 where Lloyd was assisting his father on the drawings for the Wasmuth Portfolio. From Frank Lloyd Wright: The Lost Years, 1910-1922, University of Chicago Press, 1993, p. 50.

Pauline Schindler ca. 1919. Courtesy UC Santa Barbara Art Museum, Architecture and Design Collections, Schindler Collection.

Pauline Schindler at Taliesin, 1920. Courtesy UC Santa Barbara Art Museum, Architecture and Design Collections, Schindler Collection.

"Olive Hill as Art-Theater Garden," Los Angeles Examiner, July 6, 1919, p 5.

Homesick for California and with his marriage failing, Lloyd returned to Los Angeles, filed for divorce and became his father's construction supervisor for Barnsdall's compound (see drawing above) on her recently-purchased 36-acre Olive Hill site on the eastern edge of Hollywood. (Lawrence, Frieda, "Eminence to Become Rare Beauty Spot, Los Angeles Examiner, July 6, 1919, p 5).

On his way to Tokyo in December 1919 FLW turned over the Olive Hill reins to Lloyd. An eager Schindler had written Wright on numerous occasions in early 1920 that he was more than ready to come to Los Angeles to work on the Barnsdall projects as well. FLW replied in a February 1920 letter that,

"I am provoked with Lloyd for wool-gathering again and leaving me entirely in the dark about everything. I am quite tired of maintaining a service that doesn't enlighten me when I am unable to enlighten myself regarding my own affairs. I still look toward Los Angeles as a place in which I might turn your services to good account, but I know nothing, absolutely nothing of what is going on there. And therefore the matter is in abeyance at least until I can get on the ground myself and make up my mind on what to do." (FLW, Tokyo to RMS, Oak Park, February 9, 1920, Getty Research Institute).

Model for Barnsdall Theater, Olive Hill, 1917-1920, unbuilt. From Alofsin, p. 244.

Barnsdall's ongoing and ever angrier complaints to the senior Wright in Tokyo regarding Lloyd's construction management difficulties on her project (see below) became too much for Frank to bear so in late 1920 he finally directed the ecstatic Schindler to move from Taliesin to Los Angeles to tactfully head up the project and try his best to mend fences with Barnsdall.

"New Residence Tract Opening," Los Angeles Times, March 13, 1921, p. 4. Courtesy R. M. Schindler Papers, Architecture and Design Collections, UC-Santa Barbara Art, Architecture and Design Museum.

In hindsight, Wright mistakenly insisted that Schindler stay on far too long at Oak Park improving his compound into rentable units and finding tenants for same. He also likely wanted a presence at both Taliesin (Will Smith) and Oak Park in case additional work happened to materialize. It is my contention that if Wright had entrusted the Oak Park situation to Will Smith and brought Schindler out to Los Angeles much earlier, the Olive Hill work would not have gotten so out of control in regards to the hungry contractors feeding at the wealthy Barnsdall's inheritance trough. (Frank Lloyd Wright Correspondence With R. M. Schindler, 1914-1922, Box 1, Folder 16).

Homer Laughlin Building, far right, 317 S. Broadway, John Parkinson, architect, 1897. Photo circa 1915 just prior to the opening of the Grand Central Market on the ground floor where RMS and LW would likely have often lunched. From Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

Schindler's and Lloyd Wright's business office while working on Olive Hill was in the Homer Laughlin Building (see right above) at 317 S. Broadway in downtown Los Angeles. (For much on the important patronage of Homer Laughlin, Jr. for Irving Gill, Harrison Albright and Lloyd Wright see my "Gill-Laughlin: Part II"). By the time they were working in the building the Grand Central Market had opened on the ground floor providing them quick and easy access for midday sustenance. Pauline Schindler wrote of the cramped office conditions,

"At present RMS and Lloyd Wright (who is at least six feet tall), two draftsmen and an office boy are all crowded into two small office rooms, which are otherwise already overflowing with huge drafting tables and desks and on TOP of them, various stenographers coming in to bring rush copy of contracts, while burly contractors stand about looking crafty and expensive." (Cited in Communities of Frank Lloyd Wright: Taliesin and Beyond by Myron A. Marty, Northern Illinois University Press, 2009, p. 71).

Letter envelope from Richard Neutra to R. M. Schindler, Taliesin to Laughlin Building, postmarked December 27, 1920. Courtesy R. M. Schindler Papers, Architecture and Design Collections, UC-Santa Barbara Art, Architecture and Design Museum.

It was here that Schindler's fellow Adolf Loos disciple Richard Neutra's mail arrived from a war-torn Europe imploring his help immigrating to the United States. Neutra would eventually follow in Schindler's footsteps to Taliesin in 1924-5 before finally making it to Los Angeles and Kings Road in March 1925. (For more on this see "Chats").

After a brief orientation by Wright before his mid-December departure for Japan, Schindler was thrust into a difficult position of balancing the demands of a by then angry, disenchanted, wealthy client, greedy contractors and sub-contractors, and oversight of the activities of his employer's moonlighting and likely resentful son. Schindler undoubtedly quickly learned of Lloyd's Otto Bollman house project in Whitley Heights on which he broke ground two weeks before his and Pauline's early December 1920 arrival and Frank's mid-December departure for Japan. (For more on this see my "Tina Modotti, Lloyd Wright and Otto Bollman Connections, 1920.").

A few months later in response to a request from the frustrated elder Wright for a report on Lloyd's activities Schindler tactfully replied,

"Concerning Lloyd I shall not make any reports....his relation to the office is to[o] vague for me to set upon. I should think he could send you all news himself and save me the suspicion of spreading gossip." (RMS (Los Angeles) to FLW (Tokyo), March 26, 1921, Getty Research Institute. See also author's note later below.).

Firenze Gardens, 5218-5230 Sunset Blvd., William J. Dodd, architect. Landscape possibly by Lloyd Wright. Photographer unknown, ca. 1920. From Los Angeles Public Library photo collection.

While in Los Angeles during July 1921 on his way back to Japan, FLW stayed at the Firenze Gardens Apartments (see above) for a few weeks while checking on the status of his nearby Olive Hill projects and conferring with Barnsdall. (FLW pencil note to RMS, n.d.,ca. July 1921, from Frank Lloyd Wright Correspondence With R. M. Schindler 1914-1929, Special Collections Getty Research Institute). Firenze was designed by William J. Dodd, possibly known to the elder Wright from their Midwest days, for whom Lloyd had designed numerous landscaping projects beginning as early as 1914 including the landscaping for his two personal Laughlin Park estates in 1914 and 1921 (see below for example) and possibly for Firenze Gardens as well. ("Gill-Laughlin: Part II").

Garden for Dodd Estate, Lloyd Wright, landscape architect, 1920. From Gebhard, p. 7.

Dodd was extremely well-connected with strong ties to the movie industry and local developers through his close friendship with fellow Los Angeles Athletic Club crony Frank A. Garbutt, wealthy scion of early Los Angeles pioneer and extensive land-owner Frank C. Garbutt. (For much on Garbutt see my "Playa del Rey: Speed Capital of the World, 1910-1913"). It was through Dodd that Lloyd met Garbutt, then a partner with Cecil B. DeMille with Paramount Pictures where for a period of over a year during 1916-17 Lloyd was in charge of their Set Design and Drafting Department. (Gebhard, p. p. 22). (Author's note: Dodd had recently been appointed by the Governor to the State Board of Architecture replacing retiring F. L. Roehrig. "Architect Named; W. F. [sic] Dodd Appointed to State Board by Governor," Los Angeles Times, October 24, 1919, P. II-11."Gill-Laughlin: Part II").

Dodd was also known to Schindler through Lloyd evidenced by Wright asking Schindler to deliver his mail and update him on the status of contracts at Firenze Gardens, "the place that Dodd built." (FLW pencil note to RMS, n.d. Frank Lloyd Wright Correspondence With R. M. Schindler 1914-1929, Special Collections Getty Research Institute).

A few weeks after FLW left for his final trip to Japan. At the same time Schindler was pleading for more funds Lloyd wrote his father in his "weekly report" that his "...drawing for Miss "B" is of course late" and that "Schindler frets at the time it consumes, and so it does, but it must be done." He excitedly continued on about the great deal he got on a new $2,200, 1920 Buick Roadster for only $1,500 and that he had found a new apartment closer to Olive Hill than the Hotel Lankershim (see below) which was "no cheaper than the Hotel but better."

Hotel Lankershim, southeast corner of Broadway and Seventh St., J. B. Lankershim, owner, R. B. Young, architect, 1904.

Lloyd's extravagant purchase must have somewhat irked Schindler as the project purse strings were seemingly under his control indicated by his comment that he "...put $450 in a joint account for Rudolph to draw upon that has lasted about three weeks, nor are any of these expenditures extravagant or unnecessary." By comparison, Schindler had earlier written Wright that he was able to scrape enough money together to buy a used Chevrolet. (LW (Los Angeles) to FLW (Tokyo) ca. August 1921, Frank Lloyd Wright correspondence, 1900-1959, and Frank Lloyd Wright Correspondence With R. M. Schindler 1914-1929, Special Collections, Getty Research Institute).

Los Angeles Athletic Club, 431 W. Seventh St., Parkinson and Bergstrom, architects, 1912. From the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

Uplifters Club House, Rustic Canyon, Santa Monica William J. Dodd, architect, ca. 1922. From Santa Monica Library.

Lloyd and his father had apparently attended a social event which included Dodd and the Uplifters, for whom Dodd was constructing a club house in Rustic Canyon in Santa Monica (see above), as intimated in his "weekly" report mailed to Tokyo shortly after Wright arrived in Japan in late August of 1921. He had also introduced his father to his by then very close friend from the Mather-Weston-Jordan-Smith circle, Reginald Pole, for whom he had designed numerous stage sets for his theatrical productions (see discussion later below).

By the summer of 1921 the Schindlers were also firmly intertwined within the same social orbit, having met Weston through their involvement with the Walt Whitman School where Pauline was teaching Weston's two oldest sons, Chandler and Brett. (For much more on this see my "The Schindlers and the Westons and the Walt Whitman School").

It is almost a certainty that Lloyd took his father to the Pilgrimage Play Theatre to view a performance of Wetherill's "Pilgrimage Play" starring Pole as Judas. This is evidenced by his continuing "weekly report" comments that he had,

"...joined the L.A. Athletic Club (see two above) through pressure from Dodd and the Uplifters!! (Same Uplifters). It is an expense that is heavy to bear just now but perhaps a wise one. Time will tell. Have started divorce proceedings. [Reginald] Poel sends his best and was sorry not to have seen you off. Expects to put on Shakespeare's "Hamlet" at the Trinity Auditorium next month. (For much on the Uplifters, a group of prominent L.A. Athletic Club members including Dodd and Frank Garbutt, see "Uplifters on Way to Enter Bohemia," Los Angeles Times, October 26, 1917, p. II-6 and "Uplifters Will Inspect Work on Clubhouse," Los Angeles Times, August 21, 1921, p. II-6). (Author's note: Garbutt's father's land development partner J. B. Lankershim also built the Hotel Lankershim).

He [Schindler] chafes in the (unintelligible) and has bewailed the fact that you forbade him to get in touch with Miss "B." I have not been able to give him much assistance, hardly any in fact, between the landscape work which I am pushing rapidly along and the perspectives and sickness." (LW to FLW (Tokyo) ca. late August 1921. Frank Lloyd Wright Correspondence, Getty Research Institute).Another reason Lloyd may not have given Schindler much assistance is that throughout the period he was purportedly working on Olive Hill, per published permit and lien notices in Southwest Builder & Contractor he was also moonlighting on his Otto Bollman and Weber Houses, and landscape projects for the Phoenix Country Club, Dodd's personal estate in Laughlin Park, the neighboring Kenneth Preuss Estate, and Santa Monica High School. All this was taking place during the hectic period Schindler was trying to wrap up construction activities and legal disputes on Barnsdall's Hollyhock House and Residences A and B. (Gebhard, p. 98. For much on Dodd's, Lloyd's and Irving Gill's involvement with Homer Laughlin's Laughlin Park see my "Gill-Laughlin: Part II").

In Lloyd's defense, like his father, he felt entitled to live a cultured, luxurious lifestyle which he could not do on the meager salary sporadically doled out by his father. Schindler was obviously aware of what Lloyd was up to but did not spill the beans to his employer or Barnsdall. (Author's note: Lloyd broke ground on the Otto Bollman Residence in November 1920 and received a completion notice in March 1921. He also was slapped with a lien for an unpaid lumber bill on his Weber House in May 1920. He seemingly kept both projects secret from his father during his July visit discussed below. It seems likely that Schindler would have been well aware of Lloyd's moonlighting activities and was complicit in keeping it quiet from Frank. ("Notices of Completion," Southwest Builder and Contractor, March 25, 1921, p. 35 and "Mechanics Liens," Southwest Builder and Contractor, May 13, 1921, p. 41). For much more on this see my "Tina Modotti, Lloyd Wright and Otto Bollman Connections,1920").

Frank Lloyd Wright, 1920. Photographer unknown. Published in Truth Against the World, Meehan, 1987, p. 20. Courtesy R. M. Schindler Papers, Architecture and Design Collections, UC-Santa Barbara Art, Architecture and Design Museum.

Coincidentally, Dodd was himself an amateur stage actor and performed with the Hollywood Community Theatre, a local group formed by Neely Dickson in 1917. Dickson received financial support from Cecil's brother, William C. DeMille and Aline Barnsdall at the same time she was staging her earlier-mentioned productions at the Los Angeles Little Theatre. ("Fifth Production at Community Theater," Los Angeles Times, March 11, 1918, p. II-8. Author's note: After leasing his first Laughlin Park estate to Charlie Chaplin in 1918 Dodd sold it to William's brother Cecil B. De Mille in 1920. De Mille then commissioned Dodd in 1921 to remodel it and connect it with a loggia to his residence next door to form a massive compound while Dodd was building his second Laughlin Park residence nearby. For much more on this see my "Gill-Laughlin: Part II").

After purchasing Olive Hill in 1919, Barnsdall generously offered Neely and her troupe a corner of her land for a new playhouse providing they could raise the money for construction but sadly, the project never came to fruition. (Warnack, Henry Christeen, "Hollywood Discovers the Community Theater," Los Angeles Times, November 11, 1917, p. III-18 and "Plans of Hollywood Community Theater," Los Angeles Times, August 10, 1919, p. III-29).

Kinema Theater, 642 S. Grand Ave., William J. Dodd, architect for the Kehrlein Brothers, Shirley C. Ward, builder, 1917. Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

Dodd's involvement with the Dickson troupe came just a few months after the grand opening of the Kinema Theater (see above) he designed for the Kehrlein Brothers. He likely had hopes for another theater commission knowing that Dickson had received financial backing from Hollywood Blvd. neighbors Barnsdall and William C. DeMille to establish her theater and troupe. Activities related to the grand opening of the much-anticipated 1200-seat, $500,000 movie palace were followed closely by the local press. For example, a couple months before the opening, a lengthy piece appeared describing the special load testing performed to ensure the structural integrity of the auditorium. A load of 1,500,000 pounds in the form of 6,000 sacks of concrete to simulate a full house was placed as seen below and the building passed structural inspection with flying colors. ("Gallery Stands A Severe Test," Los Angeles Times, October 21, 1917, p. V-1).