Pauline Gibling Schindler, 1920. R. M. Schindler photo. (McCoy Papers, Archives of American Art)

R. M. and Pauline Gibling Schindler, Sophie and Edmund Gibling, Dorothy Gibling and Mark Schindler at Kings Road, summer 1923. (Sweeney, p. 93). Schindler Family Collection, Courtesy Friends of the Schindler House.

I hope to build upon Sweeney's findings by concentrating more deeply upon PGS's considerable efforts to promote and market the brand of modernism produced by her notable circle of avant-garde architects, composers, musicians, designers, dancers, artists, writers, gurus and bohemian and radical friends and acquaintances. Her importance to a wider acceptance and appreciation of modern architecture and the arts in Southern California is much under-appreciated as her Kings Road, Carmel and Ojai salons, editorials, articles, exhibitions and lecture bookings generated numerous contacts which resulted in important clients for both her husband and his erstwhile partner and tenant Richard Neutra and others fortunate enough to have been in her circle.

Other useful sources were: R. M. Schindler

Pauline Gibling Schindler, from a prominent east coast family, studied music for four years at Smith College (see below) after which she moved to Chicago and taught music from 1916 to 1919 at Jane Addams ' Hull House, a settlement house for the poor and center for social reformers and intelligentsia. During Pauline's time at Smith, Addams and Emily Green Balch founded the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom for which both, on separate occasions, were to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. Pauline's mother Sophie became the Treasurer of the League. In 1919, Pauline met and married architect Rudolph Schindler, and moved with him to Taliesin, his employer Frank Lloyd Wright's home and studio. Ironically, Richard Neutra would also briefly stay at Hull House upon his arrival in Chicago from New York in March 1924 where he taught children's drawing classes to earn his keep. (RN-Hines, p. 48-9, P&F, p. 116).

' Hull House, a settlement house for the poor and center for social reformers and intelligentsia. During Pauline's time at Smith, Addams and Emily Green Balch founded the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom for which both, on separate occasions, were to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. Pauline's mother Sophie became the Treasurer of the League. In 1919, Pauline met and married architect Rudolph Schindler, and moved with him to Taliesin, his employer Frank Lloyd Wright's home and studio. Ironically, Richard Neutra would also briefly stay at Hull House upon his arrival in Chicago from New York in March 1924 where he taught children's drawing classes to earn his keep. (RN-Hines, p. 48-9, P&F, p. 116).

Top center, Pauline Gibling, and below center with cat, Dorothy Gibling at a costume party, Smith College, 1915. Archives of American Art, Esther McCoy Papers.

Frank Lloyd Wright appointed Schindler superintendent of his office for the duration of his two year period in Japan supervising the construction of the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. At the same time, with a large commission for the oil heiress, Aline Barnsdall, Wright set up office in Los Angeles, which is where the Schindler's moved in 1920. The following year Schindler set up his own, independent practice and, in collaboration with Pauline's college friend Marian Da Camara Chace and her contractor husband John, designed and built the Kings Road House with financial support from Pauline's parents. The Kings Road House, wrote the architectural historian Rayner Banham, "is perhaps the most unobtrusively enjoyable domestic habitat ever created in Los Angeles." (Banham, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, Harper & Row, 1971, p. 182).

The house reflected Pauline's social philosophy, a place of simplicity where people from all walks of life could meet together. Pauline had expressed this kind of open meeting house in a letter to her mother well before she had met Schindler. She presciently wrote from Hull House in 1916,

"One of my dreams, Mother, is to have, some day, a little joy of a bungalow, on the edge of the woods and mountains near a crowded city, which shall be open just as some people's hearts are open, to friends of all classes and types. I should like it to be as democratic a meeting-place as Hull House where millionaires and laborers, professors and illiterates, the splendid and the ignoble, meet constantly together." (Sweeney, p. 87).During this period, the lifestyle embodied in the design for their house was observed by the Schindlers (and the Neutras after they moved in in March 1925) through diet and exercise, psychoanalysis, education, and the arts of music, dance, painting and photography. The outdoor courts were dining rooms and playrooms for their toddlers, who ran free under the sun year round. They slept in the open air, ate simple meals of fruits and vegetables by the fireplaces, and wore loose-fitting garments of natural fibers closed with ties rather than buttons. At their parties, the terraces served as stages for musical and dance performances; in the audiences were many aspiring California artists, actors and writers.

Edward Weston was one of the earliest visitors to the completed house. Weston likely met the Schindlers at the Walt Whitman School around 1921 where Pauline taught and Weston's sons Chandler and Brett were enrolled. (For much more on this see my "The Schindlers and the Westons and the Walt Whitman School"). The Schindlers visited Weston's studio in the summer of 1922 and later "when the evening was ripe" the group moved over to Kings Road. Weston "[was] of course very much excited about the house, and wanting to see it by daylight. All of it a fearfully stimulating evening...RMS and I couldn't sleep, with the stimulus of the music, and Mr. Weston's pictures." (Artful Lives: Margrethe Mather, Edward Weston, and the Bohemians of Los Angeles by Beth Gates Warren, p. 253 and letter from SPG to family, July 1922). The Schindlers, and later the Neutras, would become lifelong friends and collaborators with Weston and his sons.

Richard, Dione and Frank Neutra and RMS at Kings Road, 1925. Photographer unknown. (McCoy Papers, Archives of American Art)

Former Neutra employee Harwell Hamilton Harris's very insightful introduction to Esther McCoy's Vienna to Los Angeles: Two Journeys: Letters Between R. M. Schindler

Harris described Pauline and Kings Road,

"Pauline - eager, ardent, ready for any new idea in any field - made an experience of everything and savored it to the full. ... People who didn't like her called her a poseur, which was unjust. She worked hard and did without almost all the things women commonly want, and did it with a grace few women in her position have achieved.. ... The Schindler's open house on Sunday evenings attracted the "arty" intellectuals of post-World-War I. ... Hollywood drew them like a magnet. ... Poets, playwrights, dancers, photographers and musicians were not the only visitors on these occasions. Socialists, reformers and intellectuals of all varieties were there. The talk was not chit-chat but about revolutionary ideas in all fields. The New, the Advanced. There were no fights because the participants, too, were advanced and so in fundamental agreement with one another. Most were locals; some were habitues; others were ones who came and went. Everyone felt free to bring a friend if he were interesting; it was a way to entertain." (Two Journeys, pp. 13-14).

John Bovingdon, circa 1928, Imogen Cunningham photo.

Harris then specifically recalled attendees Edward Weston, playwright and actor Maurice Browne, poet Robert Nichols, dancer John Bovingdon (see above), pianists Doris Levings and Max Pons, among others and finished with,

"Whether the group was large, filling both studios and the garden, or small and restricted to one room or the patio, the place alone raised the common above the commonplace. It freed everyone's expression. It was a tool Pauline and RMS used with imagination and skill and it deserves to be remembered."

Thanksgiving at Kings Road, 1923. Clockwise from left, Herman Sachs, Karl Howenstein, Edith Gutterson, Anton Martin Feller, E. Clare Schooler, unidentified, Betty Katz, Alexander R. Brandner, and obscured, Max Pons, to the right of Sachs. Not shown, the Schindlers and Dorothy Gibling. Photo by R. M. Schindler. From "Life at Kings Road: As It Was 1920-1940" by Robert Sweeney in The Architecture of R. M. Schindler, p. 97.

Despite the radical slant of most of the visitors to Kings Road, traditional Thanksgiving and Christmas celebrations were observed. The 1923 Thanksgiving feast seen above was attended by Herman Sachs, Karl and Edith Howenstein, Alexander R. Brandner, Betty Katz, Max Pons, E. Clare Schooler, Dorothy Gibling and others. Sachs, soon-to-be Schindler client and collaborator seen above left, established the short-lived Chicago Industrial Arts School at Jane Addam's Hull House in 1920 and directed the Dayton Institute of Art in 1921-22 before moving to Los Angeles in 1923. Karl and Edith Howenstein (above back center) were also friends of the Schindlers in Chicago where Karl had also worked at the Art Institute before moving to Los Angeles to become Director of the Otis Art Institute. The Howensteins first lived in the Kings Road guest wing for two years between 1922-4.

Edward Weston, "Betty in Her Attic," 1920. Betty Katz. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

Former Kings Road tenant Viennese architect A. R. Brandner, who would later marry Katz in 1943, recalled, "Pauline made the gatherings but it was Schindler who enjoyed them." The parties were, "...happy times, unique gatherings - the intelligentsia and desperate characters. Pauline preferred a serious party, but when Schindler and Sadakichi Hartmann got together it was glorious fun." (McCoy, p. 14, 41). A multi-talented artist, writer, critic and actor, Hartmann played the role of the Chinese prince in Douglas Fairbanks' The Thief of Bagdad in 1923 (see below). He was favorably reviewed in a July 5, 1923 L.A. Times article "New Faces and New Angles on Favorites" by Edwin Schallert. (For an interesting sidebar on the discontent caused by the film caused in China see "The Thief of Bagdad Uproar" and my "Krisel and Alexander in Hollywood").

in 1923 (see below). He was favorably reviewed in a July 5, 1923 L.A. Times article "New Faces and New Angles on Favorites" by Edwin Schallert. (For an interesting sidebar on the discontent caused by the film caused in China see "The Thief of Bagdad Uproar" and my "Krisel and Alexander in Hollywood").

Sadakichi Hartmann, 1919, Edward Weston portrait. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

"Hartmann Reading Poe at Schindler's", pen and ink, Boris Deutsch, January 8, 1928. From the exhibition catalog The Life and Times of Sadakichi Hartmann, 1867-1944 , UC-Riverside, 1970.

, UC-Riverside, 1970.

Sadakichi Hartmann in The Thief of Bagdad, 1923.

Announcement for a February 22, 1930 talk on modern art at Kings Road. From Sweeney, p. 107.

"Hartmann Reading Poe at Schindler's", pen and ink, Boris Deutsch, January 8, 1928. From the exhibition catalog The Life and Times of Sadakichi Hartmann, 1867-1944

Sadakichi Hartmann in The Thief of Bagdad, 1923.

Announcement for a February 22, 1930 talk on modern art at Kings Road. From Sweeney, p. 107.

Noted English playwright and theater troupe organizer Maurice Browne, in his autobiography Too Late to Lament

Announcement for performances of two of Browne's plays. L.A. Times, December 14, 1924.

Pauline's mother Sophie, a frequent guest at Kings Road wrote in a December 16, 1926 letter to her husband,"...when company drops in [Pauline] is a most fascinating hostess. Sunday evening it struck me again how much atmosphere, uniqueness and charm there is about her parties, and what interesting people she collects." (Sweeney, p. 104).

The marriage was not a peaceful one. Schindler was truly a Bohemian and did not respect the institution of marriage, and behaved accordingly. Pauline had wanted to consider the marriage a legal formality to satisfy her family, but was much more conventional in her response to it than she imagined she would be. (From http://www.ex-tempore.org/ExTempore96/cage96.htm). The painter Conrad Buff, who gravitated in both the Kings Road and Jake Zeitlin social orbits and commissioned Neutra in 1927 to design the garage and entryway for his Eagle Rock house and studio, said of Schindler in his UCLA Oral History,

"Schindler, besides being a disciple of Frank Lloyd Wright, was a very handsome fellow. He was quite a ladies' man, and part of his business was to make love to all the ladles he could. He had a very interesting wife, but that didn't bother him. There was quite a group of people that used to meet down at Schindler's house." (Buff Oral History).PGS and RMS's relationship finally reached the breaking point in late August 1927. Pauline packed up and left with son Mark in secrecy to avoid a confrontation. (Sweeney, P&F, p. 167). She had just weeks earlier written a highly favorable two-part review of tenant Richard Neutra's Wie Baut Amerika?

The Neutra's had previously moved into the Kings Road guest-studio in March 1925 and the Chace wing about a year later. Galka Scheyer, Kings Road guest-studio tenant while studying modern architecture with Schindler for three months over the summer of 1927, was not only witness to Pauline's departure but apparently facilitated the Lovell Health House commission by talking to Lovell, Schindler and Neutra about their mutual concerns of who would (or wouldn't) be working on the Health House design. (Sweeney, P&F, p. 171 and "Braxton Gallery, 1928-1929, Hollywood" by Naomi Sawelson-Gorse in The Furniture of R. M. Schindler, UCSB, p. 87).

"Recalling Happy Memories", Peter Krasnow, summer 1927. Galka Scheyer lecturing on The Blue Four at Kings Road. From Galka E. Scheyer and The Blue Four: Correspondence, 1924-1945 edited by Isabel Wunsche, Benteli, 2006.

edited by Isabel Wunsche, Benteli, 2006.

Galka Scheyer at Kings Road, circa 1931. (Sweeney, p. 108).

From Carmel Pauline wrote to close friend Betty Katz Kopelanoff, former lover of mutual friend Edward Weston, of her recuperative stay in Halcyon.

Browne and Van Volkenberg were, however, soon back working together on projects such as an April, 1925 performance at the Wilshire Ebell Theater by the Maurice Browne Players of Browne's "Mother of Gregory" (first performed in Carmel in 1924). ("Ebell Program for Month Out", L.A. Times, April 23, 1925, p. I-7.) Browne also announced in February, 1926 that Los Angeles would be the production headquarters for his Maurice Browne Theater Association with offices to be located in the Transportation Building and that he would be joined by Van Volkenberg. ("Nationally Known Producer Chooses City as Production Headquarters for Little Plays", L.A. Times, February 28, 1927, p. 23).

Ironically, Browne and Ellen Van Volkenburg (seen above just before Browne left her to have a child with Ellen Janson) spent time in Carmel as directors of Edward Kuster's Theatre of the Golden Bough in 1924. In his autobiography Browne recalled his former San Francisco student,

Sometime around 1921 Pauline met RMS’s most important client through the Barnsdall connection as she, Leah Press Lovell and sister Harriet Press Freeman, radical friends of Aline. Leah and Pauline were involved with Barnsdall’s progressive kindergarten she commissioned for her daughter and other selected children at Hollyhock House (see above). (Sun-Hines, p. 156). Through Pauline’s connection with Leah and Harriet, Schindler became architect to the both the Lovells and Freemans. Beginning in 1922 RMS designed three projects for the Lovells, a mountain cabin in Wrightwood, a farmhouse in Fallbrook and the iconic Beach House in Newport Beach which was completed in 1926.

By 1924, RMS had also essentially replaced Wright as Aline Barnsdall’s personal architect and by 1928 replaced Wright as Sam and Harriet Freeman's architect. Beginning in 1928 Schindler was also hired to design furniture for Wright’s Freeman House where, over the next 25 years, he designed two guest apartments and other alterations and over 35 pieces of furniture. (See “Freeman House, 1928-1933, Hollywood Hills” by Jeffrey M. Chusid in The Furniture of R. M. Schindler , UCSB, p. 100).

, UCSB, p. 100).

It has been speculated by some that Schindler was having an affair with Leah and/or Harriet which could have contributed to Pauline’s 1927 departure from Kings Road and might have come into play in Philip Lovell’s decision to award Neutra the Health House commission. See both Hines books for the most complete analysis of how this commission came about. (See also my Selected Publications of Esther McCoy for much more discourse on the Lovell Health House Commission).

As she had done at Kings Road, Pauline rapidly assimilated into the Carmel arts community. She soon began contributing an unsigned column, "The Black Sheep," to the Carmel Pine Cone (see photo above). Appearing 11 times between November 1927 and March 1928, she described it as a "new critical department which does not promise to behave itself too well," but that it would be, "young, fearless, honest, and vital." She focused mainly on music, local issues and events. Pauline was also named drama critic for Carmel for the Christian Science Monitor. (Sweeney, p. 104). Thus, she may likely be responsible for the four late 1920s and early 1930s Monitor articles on Neutra projects listed in my Neutra bibliography. During her tenure at the Carmel Pine Cone, the Harrison Memorial Library designed by Bay Area architect Bernard Maybeck was opening on Ocean Avenue (see below).

Left, The Carmelite masthead for May 23, 1928, the last issue before Pauline's editorship began. Right, Masthead after Pauline's redesign. The Carmelite, July 4, 1928, front cover. (from Sweeney, p. 105).

Announcement for a series of 1930 Bovingdon performances at Kings Road. From Sweeney, p. 107.

The Carmelite, March 20, 1929. (From my collection).

Richard Buhlig, 1922. Margrethe Mather portrait. From Margrethe Mather & Edward Weston: A Passionate Collaboration by Beth Gates Warren, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2001, p. 97.

The Carmelite, July 3, 1929, pp. 7 -8. (From my collection).

Henry Cowell, 1923. Margrethe Mather portrait. From Margrethe Mather & Edward Weston: A Passionate Collaboration by Beth Gates Warren, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2001, p. 111.

In the November 28, 1928 issue, Pauline announced a Richard Neutra lecture (see two above images) on modern architecture she arranged at the Denny-Watrous Gallery "and a Dione Neutra concert in Dene Denny and Hazel Watrous's "Harmony House." (See below) (The Arts: Dione Neutra Will Sing in Carmel," The Carmelite, November 28, 1928, p. 5). In a lengthy companion piece in the same issue she wrote,

With Richard just wrapping up the design for the Lovell Health House, the Neutra's took a much-needed week's vacation for the lecture and concert. They stopped on the way to Carmel after a delightful drive along the coast to observe "the strange inhabitants of Oceano." (P&F, p. 206). The Neutra's son Raymond recalls his mother Dione "talking about walking in the Oceano Dunes and coming across a naked hermit friend in his hut." (July 15, 2010 e-mail message from Raymond Neutra to the author). Dione's description of the two stormy night events in Carmel are recorded in a December 1928 letter to her parents. (P&F, p. 173).

Pianist Dene Denny and Hazel Watrous in their home "Harmony House."

In 1926 Denny and Watrous founded the Carmel Music Society. In November of the same year (see above) Dene appeared in Los Angeles with avant-garde composers Henry Cowell (featured in the July 3, 1929 issue of The Carmelite) and Dane Rudhyar (one of Pauline's contributing editors) at the New Music Society with Pauline undoubtedly in attendance. She made other Los Angeles appearances over the next few years. In 1928 the official partnership, Denny-Watrous Management, was launched. In the same year they leased the Theatre of the Golden Bough from Edward Kuster and in twelve months produced a dozen concerts and eighteen plays routinely reviewed by Pauline in The Carmelite , including Ferenc Molnar's "Liliom," Eugene O'Neill's "Emperor Jones" and Henrik Ibsen's "Ghosts", all recently presented for the first time in English in New York. They then opened the Denny-Watrous Gallery, Carmel's first art gallery, using the space to present plays and concerts, as well as art. Here was the first known American performance of Bach's "Art of the Fugue." http://www.carmelresidents.org/News0303.html

The Carmelite, March 20, 1929, p. 3. (From my collection).

Pauline and Mark's first stop on what would become an nine-year sojourn away from Kings Road was at Ellen Janson's house in Halcyon, a small bohemian community of artists, poets, intellectuals and religious mystics founded by Theosophists in 1903 to which she later frequently returned. She probably learned of Halcyon from Maurice Browne (Sweeney, p. 96) and his lover of five years, actress and poet Ellen Janson, who possibly attended Browne's Keyserling lecture at Kings Road the previous year. Janson, and Browne had spent much of 1924 in Halcyon conceiving and giving birth to their son "Praxy." (Sweeney, p. 104 and Too Late to Lament, p. 279). Browne had also been promoting Janson's career as a poet in such publications as Contemporary Verse. (See below).

Excerpt from "Contributors," Contemporary Verse claiming the discovery of contributor Ellen Janson, Vol. XII, No. 5, November, 1921, p. 2.

Janson had an aunt living in Halcyon who found them a house through Theosophist John Varian who becomes important later in this article. Browne, in his autobiography, writes about himself and Janson using their love-nest in Halcyon as a base, traveling up and down the California coast camping under the stars. (Too Late to Lament , pp. 278-9). Browne wrote of the conception,

, pp. 278-9). Browne wrote of the conception,

"He was gotten, willfully, at noon of a still burning August day on one of those beaches; we both knew that he would be a male. His mother and I, living in a dream world, believed that once he was surely conceived she could go happily forth into the world alone, carrying him, and I return to my work with Nellie Van." Browne soon divorced Van Volkenberg, married Janson and moved into a new "redwood shack" built for Ellen by her parents in Halcyon. (Too Late to Lament, pp. 280).

Ellen Janson Browne and son Praxy ca. 1926. Photographer unknown. (Tingley, Donald F., "Ellen Van Volkenburg, Maurice Browne and the Chicago Little Theatre," Illinois State Historical Society Journal, Autumn, 1987, p. 144.

From Carmel Pauline wrote to close friend Betty Katz Kopelanoff, former lover of mutual friend Edward Weston, of her recuperative stay in Halcyon.

"In Halcyon I became immediately, very very ill. I was in Ellen's [Janson] house. My mother, father, and Mark, had to leave it and live in another cottage, because it was not endurable to me to hear a voice or a footstep, or to feel a presence. So I lay for many weeks. I became well again because of a remarkable nurse; the great peace of the landscape; and the felt powerful near spirits of Borghild [Janson, Ellen's aunt] and of Hugo [Seelig, Dunite poet discussed later herein]. As I owe my life to you and to Galka Scheyer, - so I owe the sense of peace and immeasurable richness of the universe, to these separate two, each in a superlative solitude." (PGS to Betty Katz Kopelanoff, December 22, 1927. Letter in possession of Betty's great niece Dottie Ickovitz.)A year and a half later Pauline wrote of Halcyon in The Carmelite as,

"...a strange little settlement with an astounding quality...if you were impervious to a thing called "spirit" which so palpably, almost visible, governs here, you would say that the houses were drab little shacks. And yet again and again...down to Halcyon...will flee from the civilization of cities, people of cultivated minds and tastes, - for a day or a week in Halcyon. There are Theosophists here, and a temple, - but it is not that which causes it all. It is a quality of universal as light. Can it be a climatic thing, - the radiation at Halcyon of forces from the earth which produce a human type of unusual harmoniousness and serenity, - as the climate of Carmel by contrast produces its inhabitants over-stimulation and cerebral scintillation." (The Carmelite, March 6, 1929).

From Carmel-By-The-Sea by Monica Hudson, Arcadia, 2006, p. 85. Note the multi-talented Kings Road salon attendee, actor and noted city planner Carol Aronovici on the left who, while wearing his City Planner hat, collaborated with RMS and Neutra on the 1928 Richmond, California Civic Center project and other projects under their Architectural Group for Commerce and Industry (AGIC) partnership.

Ironically, Browne and Ellen Van Volkenburg (seen above just before Browne left her to have a child with Ellen Janson) spent time in Carmel as directors of Edward Kuster's Theatre of the Golden Bough in 1924. In his autobiography Browne recalled his former San Francisco student,

"[Kuster] proposed to build a playhouse in Carmel; it would have a full sky-dome, the first in the country. The three of us spent months pulling his plans to pieces; the Theatre of the Golden Bough was to be the best equipped and most beautiful in America. It was. Kuster invited us to open it with a play written by me, to run a summer-school there, and to direct it afterwards as an art-theatre." (Too Soon to Lament, p. 271. Author's note: For much more on Browne, Van Volkenburg and the Theatre of the Golden Bough see my "The Schindlers in Carmel, 1924").

Coincidentally, Browne and Van Volkenberg were originally involved with Aline Barnsdall as early as 1915 in Chicago where, in 1912, they had established the Chicago Little Theatre, a critically acclaimed experimental troupe inspired by the Irish Players at Dublin's Abbey Theatre. Pauline's knowledge of Browne and Van Volkenberg dated all the way back to their Chicago Little Theatre days as the pair had collaborated with her mentor, Hull House and Women's International League for Peace and Freedom founder Jane Addams, to produce a national tour of Euripides' "peace play" The Trojan Women during her employment there.

Eager to start her own theater company in Chicago and produce her own plays, Barnsdall offered to build Browne and Van Volkenburg a larger, more modern theater and commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design preliminary plans for in 1915. Aline put the plans on hold as she moved to California in 1916 and opened a theater in rented space in Los Angeles. She then commissioned Wright to begin Hollyhock House on Olive Hill, the Schindler's raison d'etre for moving to Los Angeles in 1920, originally planning to add a theater later which never came to pass. (From Frank Lloyd Wright: Hollyhock House and Olive Hill by Kathryn Smith, Rizzoli, 1992, pp. 21-23). When the Chicago Little Theatre failed in 1917, Van Volkenberg and Browne headed up theater troupes in both Seattle, where he met Janson, and on Broadway in New York to much critical acclaim. (NY Times Archives. See my "Schindlers-Westons-Kashevaroff-Cage" for much more on the Browne-Schindler-Janson relationships. Author's note: Coincidentally, RMS (and Pauline?) also knew Ellen Janson from her early 1920s involvement with one of the members of Aline Barnsdall's experimental theater group. (Sheine, note 27, p. 283).

by Kathryn Smith, Rizzoli, 1992, pp. 21-23). When the Chicago Little Theatre failed in 1917, Van Volkenberg and Browne headed up theater troupes in both Seattle, where he met Janson, and on Broadway in New York to much critical acclaim. (NY Times Archives. See my "Schindlers-Westons-Kashevaroff-Cage" for much more on the Browne-Schindler-Janson relationships. Author's note: Coincidentally, RMS (and Pauline?) also knew Ellen Janson from her early 1920s involvement with one of the members of Aline Barnsdall's experimental theater group. (Sheine, note 27, p. 283).

Aline Barnsdall and daughter Betty, ca. 1920. From L.A. Public Library Photo Collection.

Mark and Pauline Schindler and Leah Lovell and children in Leah's "School in the Garden," Argyle Avenue, Hollywood, ca. 1925.

Sometime around 1921 Pauline met RMS’s most important client through the Barnsdall connection as she, Leah Press Lovell and sister Harriet Press Freeman, radical friends of Aline. Leah and Pauline were involved with Barnsdall’s progressive kindergarten she commissioned for her daughter and other selected children at Hollyhock House (see above). (Sun-Hines, p. 156). Through Pauline’s connection with Leah and Harriet, Schindler became architect to the both the Lovells and Freemans. Beginning in 1922 RMS designed three projects for the Lovells, a mountain cabin in Wrightwood, a farmhouse in Fallbrook and the iconic Beach House in Newport Beach which was completed in 1926.

Freeman House living room with Schindler-designed furniture. Photo by Julius Shulman, 1953. From “Freeman House, 1928-1933, Hollywood Hills” by Jeffrey M. Chusid in The Furniture of R. M. Schindler , UCSB, p. 100. See also Getty Research Institute.

, UCSB, p. 100. See also Getty Research Institute.

By 1924, RMS had also essentially replaced Wright as Aline Barnsdall’s personal architect and by 1928 replaced Wright as Sam and Harriet Freeman's architect. Beginning in 1928 Schindler was also hired to design furniture for Wright’s Freeman House where, over the next 25 years, he designed two guest apartments and other alterations and over 35 pieces of furniture. (See “Freeman House, 1928-1933, Hollywood Hills” by Jeffrey M. Chusid in The Furniture of R. M. Schindler

It has been speculated by some that Schindler was having an affair with Leah and/or Harriet which could have contributed to Pauline’s 1927 departure from Kings Road and might have come into play in Philip Lovell’s decision to award Neutra the Health House commission. See both Hines books for the most complete analysis of how this commission came about. (See also my Selected Publications of Esther McCoy for much more discourse on the Lovell Health House Commission).

Despite an offer to stay at Ellen Janson's house in Halcyon over the winter of 1927, Pauline left for Carmel on October 19 where she would remain for the next two years. (Sweeney, p. 103). She likely heard great things about the artist's colony and bohemian lifestyle of Carmel from Galka Scheyer who had arranged a Blue Four exhibition there in 1926. She wrote to later Schindler client, Kings Road tenant and lifelong friend Betty Katz Kopelanoff of her exciting beginnings in Carmel.

"...In Carmel I have begun to write. Like you, I make an irrelevant journalistic beginning. I write a page a week for the Carmel Pine Cone. Musical criticism, life, the arts, etc., in a serious-sophisticated style. I have carte blanche, - and am a tremendously privileged freelance. Carmel is so small a community that my page, "The Black Sheep," immediately gives me an active relation to everything in it. This provides stimulating encouragement as well as discipline. I have already been asked to start a Nursery School course for mothers; direct some children's glee clubs; start a school; share in the publication of a new sophisticated periodical. And have met, in this short time, more people to enjoy with completely sympathetic exchange than in all my years in Los Angeles. There are a few startlingly dynamic people, like Mr. Lincoln Steffens; but the rarer treasures, and the richest, are some five or six who live lives of superlative interior richness and beauty." (PGS to Betty Katz Kopelanoff, December 22, 1927. Letter in possession of Betty's great niece Dottie Ickovitz.)

Carmel Pine Cone Office and later the Denny-Watrous Gallery, Dolores Ave., M. J. Murphy Builder, Lewis Josselyn photo. From Carmel-By-The-Sea by Monica Hudson, Arcadia , 2006.

, 2006.

As she had done at Kings Road, Pauline rapidly assimilated into the Carmel arts community. She soon began contributing an unsigned column, "The Black Sheep," to the Carmel Pine Cone (see photo above). Appearing 11 times between November 1927 and March 1928, she described it as a "new critical department which does not promise to behave itself too well," but that it would be, "young, fearless, honest, and vital." She focused mainly on music, local issues and events. Pauline was also named drama critic for Carmel for the Christian Science Monitor. (Sweeney, p. 104). Thus, she may likely be responsible for the four late 1920s and early 1930s Monitor articles on Neutra projects listed in my Neutra bibliography. During her tenure at the Carmel Pine Cone, the Harrison Memorial Library designed by Bay Area architect Bernard Maybeck was opening on Ocean Avenue (see below).

Harrison Memorial Library, Ocean Avenue, Bernard Maybeck. Postcard from the internet.

Through her association with the Pine Cone Pauline became involved with Carmel's new progressive weekly The Carmelite edited by Stephen A. Reynolds, for whom she penned the columns "Stage and Screen" and "With the Women" and other articles under her byline in early 1928. Pauline's April 25th "With the Women" column for example, reported on the annual P.T.A. conference in Salinas, the recent activities of Anne Martin, regional director of the Women's International League of Peace and Freedom founded by her Hull House employer and mentor Jane Addams, and a meeting of 35 alumnae of her alma mater, Smith College, at Point Lobos.

Reynolds initially announced the weekly as, "a periodical which will without fear or favor give voice and light on both sides of a mooted question affecting the artistic or practical in village life." Reynolds, at odds with the entrenched positions of the Carmel Pine Cone, used his new vehicle as a way to publish politically-charged editorial jibes beginning in February 1928. Pauline quickly advanced to editorial assistant and and was anticipating becoming managing editor by mid-April. (Sweeney, p. 105). In a May 7, 1928 letter to her father she wrote of The Carmelite as being, "a liberal-radical weekly, in whose pages the visiting or resident intelligentsia, from Lincoln Steffens to Robinson Jeffers, all had a word." After only 16 weeks at the helm, Reynold's turned over The Carmelite to Pauline after the May 30 issue.

Interior court of the Seven Arts Building, Home of The Carmelite, and Edward Weston's studio up stairway to the right. George A. Robinson photo.Reynolds initially announced the weekly as, "a periodical which will without fear or favor give voice and light on both sides of a mooted question affecting the artistic or practical in village life." Reynolds, at odds with the entrenched positions of the Carmel Pine Cone, used his new vehicle as a way to publish politically-charged editorial jibes beginning in February 1928. Pauline quickly advanced to editorial assistant and and was anticipating becoming managing editor by mid-April. (Sweeney, p. 105). In a May 7, 1928 letter to her father she wrote of The Carmelite as being, "a liberal-radical weekly, in whose pages the visiting or resident intelligentsia, from Lincoln Steffens to Robinson Jeffers, all had a word." After only 16 weeks at the helm, Reynold's turned over The Carmelite to Pauline after the May 30 issue.

Under Pauline's leadership The Carmelite became much more than a local newspaper. It was a leading-edge progressive publication reporting on many of the left-leaning issues of the day, the local arts and literary scene and reviews of cultural events in San Francisco and even far away Los Angeles. She used the paper to express her own artistic and political opinions and promote her personal interests and the work of her friends. She was truly in her element during this period of her life. In a May 7, 1928 letter to her father she stated that she wrote about half the paper which is probably an understatement based on the issues in my collection. (Sweeney, p. 105). She also featured many of the people from her Los Angeles circle of friends, Kings Road salon participants and former tenants such as Edward Weston, Henrietta Shore, John Bovingdon, Carol Aranovici, Ellen Janson, Galka Scheyer and many others. The paper was headquartered in the new Seven Arts Building on Ocean Avenue in the heart of Carmel (see photo above).

Left, The Carmelite masthead for May 23, 1928, the last issue before Pauline's editorship began. Right, Masthead after Pauline's redesign. The Carmelite, July 4, 1928, front cover. (from Sweeney, p. 105).

One of the earlier issues under Schindler's editorship, July 4, 1928, featured on the front page a photo of and a poem by occasional tenant and regular performer at Kings Road, John Bovingdon and announced his upcoming performance at the Theatre of the Golden Bough and a party in his honor at the Steffens' house. (see above right). The issue also included an article by Pauline on the upcoming visit by former Hull-House employer, mentor, and major influence on her leftist political beliefs, Jane Addams and an article on noted city planner and actor Carol Aronovici's talk "Planning the Seaside Town."

The July 11th cover featured a photo of Point Lobos by Johan Hagemeyer and a feature story "The Good Neighbor" under Pauline's byline on her erstwhile mentor Jane Addams and her Hull-House. Pauline also included a brief article "Maurice Browne in a Second Edition" reporting on Ellen Janson Browne and four-year old Maurice, Jr. passing through town and the whereabouts of Maurice Sr. currently producing a play of George Bernard Shaw's in London. Pauline wrote of Browne,

The July 11th cover featured a photo of Point Lobos by Johan Hagemeyer and a feature story "The Good Neighbor" under Pauline's byline on her erstwhile mentor Jane Addams and her Hull-House. Pauline also included a brief article "Maurice Browne in a Second Edition" reporting on Ellen Janson Browne and four-year old Maurice, Jr. passing through town and the whereabouts of Maurice Sr. currently producing a play of George Bernard Shaw's in London. Pauline wrote of Browne,

"In Carmel he remains a memory and an influence, for Morris Ankrum, George Ball, and many others here busy with the stage have had their first dramatic training under the direction of this intense and passionate artist."The July 18th issue featured a cover photo of Jane Addams and a headline announcement of her upcoming speaking engagement at the Golden Bough. It also included a letter "To Carmel With Love From Halcyon" from editorial board member Dora Hagemeyer who was spending the summer in the home of Ellen Janson and Maurice Browne and an announcement for the upcoming opening of an exhibition of the paintings of Henrietta Shore in the Hagemeyer Studio on Ocean Avenue. In her lengthy and insightful review of avant-garde pianist Henry Cowell's performance at the Golden Bough which was illustrated with a Virginia Tooker woodcut, Pauline wrote,

"The program was a study of the development of the tone cluster principle which used as a method by a versatile artist of unusually free imagination. Of these, some are small in range, and contribute a scintillating brilliance to simple diatonic material. It is as though the tones had passed through a sound prism, and been broken up into their parts and overtones."Shore's "The Bull Fight" then appeared on the cover of the July 25th issue along with a poem by Dora Hagemeyer and an article discussing the financial crisis Edward Kuster was facing in his attempt to keep the Theatre of the Golden Bough open. Also in that issue, Pauline reported at length on the activities surrounding Jane Addams visit to Carmel. After a Wednesday luncheon in her honor at the Mission Tea House, Addams lectured on Sunday evening on "Governmental Steps Toward World Peace" to an overflow crowd at the Golden Bough Theatre which was followed by a reception at the home of Lincoln Steffens and Ella Winter. Addams (see below) was on her way to Los Angeles for four days of speaking engagements and a banquet in her honor at the Biltmore Hotel and then to Hawaii for the Pan-Pacific Women's Congress and Congress of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. ("Los Angeles Will Honor Sociologist", L.A. Times, July 26, 1928, p. I-11). It is likely Addams and Neutra's paths also crossed during her Los Angeles visit.

Jane Addams, Los Angeles, July 1928. George W. Haley photo for the L.A. Herald-Examiner. Courtesy of Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

The August 1st issue featured Edward Weston's "Shell" on the front cover, a review of Robinson Jeffers' new book of poems Cawdor, and the marriage of Neutra and Schindler AGIC partner and Carmelite contributing editor Carol Aronovici. The August 15th number had Ellen Janson's poem "Sirius" on the front page. The following week's edition profiled San Francisco arts patron Albert M. Bender and reported on his visit to the Jeffers, Stanley Wood and the Steffens and his accompaniment by Mr. and Mrs. Ansel Adams.

The Carmelite, March 20, 1929. (From my collection).

Richard Buhlig, 1922. Margrethe Mather portrait. From Margrethe Mather & Edward Weston: A Passionate Collaboration by Beth Gates Warren, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2001, p. 97.

PGS reviewed concerts and plays at the Theater of the Golden Bough, the Carmel Playhouse, the Carmel Theater Guild, and Forest Theater, exhibitions at the Denny-Watrous Gallery, published wood block and linoleum cut prints by artists such as early Kings Road visitor and now Carmelite staff artist Virginia Tooker (see above), Esther Bruton, Stanley Wood, Ray Boynton and others. Music was obviously one of her major focuses as she routinely reported on concerts, many of which she arranged, by major, avant-garde pianists passing through Carmel on there way between Los Angeles and San Francisco. She covered performances by dancers John Bovingdon, Ruth Austin and Grace Burroughs, pianists Imre Weisshaus, Dene Denny, future lover John Cage mentors Henry Cowell (see below left and center) and Richard Buhlig (see above right and center), violinist Albert Spalding, guru Jiddu Krishnamurti and numerous others. She reported on important events, exhibitions and concerts she attended in San Francisco such as her December 26, 1928 review of "The Blue Four" exhibition at the Berkeley Museum organized by Galka Scheyer.

The Carmelite, July 3, 1929, pp. 7 -8. (From my collection).

Schindler published reviews on such events as the the Progressive Education Conference at St. Louis, the sixth convention of the Workers (Communist) Party in New York, a "hunger march" of the National Unemployed workers Committee Movement in London, the World Youth Peace Conference in Vienna, and editorials on subjects like "The Anachronism of Cities" attended by Carol Aronovici, former R. M. Schindler and Richard Neutra AGIC partner on the 1928 Richmond, California Civic Center Plan. (see above right). She also published poetry by Robinson Jeffers, Galka Scheyer, Dora Hagemeyer, and others and regularly wrote insightful reviews of books that struck her fancy.

Schindler, Pauline, "Richard Neutra, Modern Architect to Speak Here," The Carmelite, November 28, 1928, p. 1. Courtesy Harrison Memorial Library, Carmel-by-the-Sea, CA.

Neutra Lecture announcement, The Carmelite, November 28, 1928, p. 7. Courtesy Harrison Memorial Library, Carmel-by-the-Sea, CA.

In the November 28, 1928 issue, Pauline announced a Richard Neutra lecture (see two above images) on modern architecture she arranged at the Denny-Watrous Gallery "and a Dione Neutra concert in Dene Denny and Hazel Watrous's "Harmony House." (See below) (The Arts: Dione Neutra Will Sing in Carmel," The Carmelite, November 28, 1928, p. 5). In a lengthy companion piece in the same issue she wrote,

"Richard Neutra, who lectures in Carmel at the studio of Denny and Watrous next Sunday evening, is what we might call a direct architectural descendant of Louis Sullivan. Every profession and every art which has great teachers has its lineages. The greatest of those who called Sullivan "Master" was Frank Lloyd Wright. ... Louis Sullivan became a great influence upon American architecture because he could not only understand consciously what he was driving at; he could not only build buildings which illustrated the principle that form follows function; but he could make his meaning clear to the rest of the world. Richard Neutra is one of the two or three true descendants of the lineage of Sullivan and Wright, to whom architecture is not merely an expression of a civilization but a conditioning agent of future cultures." (Schindler, Pauline, "The Architecture of the Future," The Carmelite, November 28, 1928, p. 11)Below is a photo of how Dione may have dressed for the Denny-Watrous-sponsored event in Carmel.

Dione Neutra in performance at Kings Road, 1928. From Nature Near: Late Essays of Richard Neutra , edited by William Marlin, Capra Press, 1989, p. 47.

, edited by William Marlin, Capra Press, 1989, p. 47.

With Richard just wrapping up the design for the Lovell Health House, the Neutra's took a much-needed week's vacation for the lecture and concert. They stopped on the way to Carmel after a delightful drive along the coast to observe "the strange inhabitants of Oceano." (P&F, p. 206). The Neutra's son Raymond recalls his mother Dione "talking about walking in the Oceano Dunes and coming across a naked hermit friend in his hut." (July 15, 2010 e-mail message from Raymond Neutra to the author). Dione's description of the two stormy night events in Carmel are recorded in a December 1928 letter to her parents. (P&F, p. 173).

Excerpts from Pauline's review in the next issue read,

"He cited the principle which is the alpha and the omega of modern architecture, "Form Follows Function," and distinguished between the functional architecture of the true modern, as compared with the formalist architecture of the earlier pseudo-classicists in the United States who took the Greek Doric column (italics mine) and thought they could make an American architecture with it. It is not the architect who now makes architecture said Mr. Neutra, but the situation out of which it arises. He clarified this by criticizing adversely several typically false buildings including the Chicago Tribune Building...

Mr. Neutra's lecture so well achieved his purpose that his audience not only listened without resistance to his startling statement of modernistic principles, but were afterwards to respond with sympathy and understanding to photographs of advanced architecture, much of it his own, which were hung on the walls." (Schindler, Pauline, "Neutra Renders Modern Architecture Intelligible," The Carmelite, December 5, 1928, p. 4).Denny and Watrous met at a party in the studio of a mutual friend in 1922. To further their education, they decided to go to New York by way of Carmel. Here they found a city almost entirely dedicated to the arts. They returned in 1925 and lived over a garage while Hazel designed their "Harmony House," on East Dolores, 4 N. of 2nd. One of the problems that faced people moving to Carmel was finding a way of making money. Hazel solved this by designing houses, some 36 of them. They were innovative in design -- she drew on the Arts and Crafts movement with exposed beams and redwood on the interior and board and batten exteriors. Large picture windows, painted shingles and pastel colors for the exterior walls were also featured.

The houses were extremely popular, and introduced a new style for Carmel architecture. "Harmony House" with its two-story picture window, flanked by two grand pianos (see above) and warmed by a fireplace, became the gathering place for informal recitals, lectures and other gatherings. Here pianist Henry Cowell, future mentor to John Cage and frequent denizen of the aforementioned Halcyon, demonstrated his entirely radical tone clusters and Richard Neutra lectured on modern building design. Pauline Schindler, by then a friend of the duo, regularly attended and reported on these events in The Carmelite, some of which, such as the Neutra lecture, she helped organize.

November 20, 1926 Los Angeles Times announcement from ProQuest.

In 1926 Denny and Watrous founded the Carmel Music Society. In November of the same year (see above) Dene appeared in Los Angeles with avant-garde composers Henry Cowell (featured in the July 3, 1929 issue of The Carmelite) and Dane Rudhyar (one of Pauline's contributing editors) at the New Music Society with Pauline undoubtedly in attendance. She made other Los Angeles appearances over the next few years. In 1928 the official partnership, Denny-Watrous Management, was launched. In the same year they leased the Theatre of the Golden Bough from Edward Kuster and in twelve months produced a dozen concerts and eighteen plays routinely reviewed by Pauline in The Carmelite , including Ferenc Molnar's "Liliom," Eugene O'Neill's "Emperor Jones" and Henrik Ibsen's "Ghosts", all recently presented for the first time in English in New York. They then opened the Denny-Watrous Gallery, Carmel's first art gallery, using the space to present plays and concerts, as well as art. Here was the first known American performance of Bach's "Art of the Fugue." http://www.carmelresidents.org/News0303.html

The Carmelite, March 20, 1929, p. 3. (From my collection).

In 1929 Hazel Watrous became associated the Seven Arts Press which printed The Carmelite. (See above). In 1935 Denny and Watrous established Carmel's now-famed annual Bach Festival, a continuing highlight of the town's social season.

The Carmelite, March 20, 1929, front page. (From my collection).

Left, poems by Galka E. Scheyer. Right, an example of Pauline's crisp ad and page layout. The Carmelite, July 3, 1929, pp. 5 & 9. (From my collection).

Robinson Jeffers, Carmel, May 1929. Edward Weston portrait from Weston's Westons: Portraits and Nudes by Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. (From my collection). Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

Robinson Jeffers, Time, Vol. XIX, No. 14, April 4, 1932. Edward Weston cover photo.

The Bruton Sisters, Helen, Margaret and Esther (right). Imogen Cunningham portrait. From "The Brutons and How They Grew" by Dorothy Puccinelli, California Arts & Architecture, October 1940, p. 18. (From my collection).

Pauline published wood block and linoleum cut prints by Esther Bruton (see above 2 images), Carmelite staff artist and early Kings Road visitor Virginia Tooker, Carmelite contributing editors Stanley Wood and Ray Boynton, also a faculty member at the California School of Fine Arts (see below) and others. She published a Special Robinson Jeffers issue featuring his poetry, and also published poems by Dora Hagemeyer (see above front page), sister-in-law of photographer Johan Hagemeyer, long-time friend of Edward Weston, and erstwhile Schindler House tenants and briefly roommates Galka Scheyer (see below) and John Bovingdon (see earlier). PGS also published Scheyer's article "Free, Imaginative and Creative Work in Drawing and Painting" in the June 26th issue on the work of her art students at the Anna Head School for Girls in Berkeley which was selected for European and West Coast exhibition tours sponsored by the American Federation of Arts. (For more on this see my Foundations of Los Angeles Modernism: Richard Neutra's Mod Squad).

Raymond Boynton, circa 1940. Imogen Cunningham portrait.

Ray Boynton woodcut. The Carmelite, March 27, 1929, front cover. (From my collection).

Ray Boynton woodcut. The Carmelite, March 27, 1929, front cover. (From my collection).

Left, poems by Galka E. Scheyer. Right, an example of Pauline's crisp ad and page layout. The Carmelite, July 3, 1929, pp. 5 & 9. (From my collection).

Pauline's circle ran ads in The Carmelite which she took great pleasure in designing, as she did redesigning the front page masthead beginning with the May 30, 1928 issue, her first at the helm as editor. (see earlier covers above). The page layout and ad design in the July 3, 1929 issue (above right) includes ads for contributing editors Edward Weston and Stanley Wood and supporter Dene Denny.

Robinson Jeffers, Time, Vol. XIX, No. 14, April 4, 1932. Edward Weston cover photo.

In 1930 Pauline had a review of Robinson Jeffers' poetry published in the prestigious literary journal Transition edited by Eugene Jolas in which she called him "a major American poet." She was also likely responsible for the article "American Nature Photos" featuring Edward Weston's work in the same issue. Pauline published a review titled “Poet on a Tower” of Jeffers' latest book of poems, Dear Judas, in the April 30, 1930 issue of Survey Graphic. This period was the pinnacle of Jeffers' fame as evidenced by Weston's April 4, 1932 Time Magazine cover photo (see above). Weston, (see portraits below) one of the earliest recruits to the Schindler's Kings Road circle with his first enthusiastic visit recorded as being in May 1922, became a lifelong friend. (Sweeney, p. 92).

Left, Edward Weston circa 1940s. Ansel Adams Portrait. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

Right, Weston portrait by Henrietta Shore, 1927. (From Henrietta Shore: A Retrospective Exhibition: 1900-1963, Monterey Peninsula Museum of Art, p. 48).

"Edward Weston on the Way" by Pauline Schindler, The Carmelite, December 26, 1928, p. 2. (From my collection).

Johan Hagemeyer Studio, Carmel. Photo courtesy OAC and U.C. Berkeley Bancroft Library, Johan Hagemeyer Photo Collection.

Tired of city life, Weston moved to Carmel in early January 1929, trading spaces from a temporary stay in fellow photographer Johan Hagemeyer's studio in San Francisco to renting his Carmel summer studio. Pauline's article "Edward Weston on the Way" in the issue above announced the impending arrival of another friend from her Kings Road salons and soirees. Weston described the move at length in his Daybooks. (Weston, pp. 99-108). Pauline published Dora Hagemeyer's poetry periodically in The Carmelite. (In 1923 Hagemeyer opened a portrait studio in San Francisco and also built a summer studio in Carmel (see above) which soon became a meeting place for artists and intellectuals. Weston and Hagemeyer had a falling out in April 1931 over the studio lease agreement. Weston then moved his studio to the Seven Arts Building upstairs from The Carmelite's offices. (See photo below). (DaybooksII, April 14 & 28, 1931, pp. 213-5).

Weston Studio, Seven Arts Building, CarmelLewis Josselyn photo.

.jpg)

Left, Johan Hagemeyer, 1928. Edward Weston portrait. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents. Right, Johan Hagemeyer and Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather, 1921. From Margrethe Mather & Edward Weston: A Passionate Collaboration by Beth Gates Warren, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2001, p. 85.

Pauline properly introduced Weston to Carmel's bohemian "society" at a reception for the Kedroff Quartet after their performance. Weston's Daybook entry reads,

"To the Kedroff Quartet: the most exquisite vocal music I have heard. The folk-songs were especially thrilling, and the Strauss Waltz! ... After, I went with Pauline to a reception for the Quartet, and there met Carmel "society," everyone that I should meet I suppose! I have certainly been flatteringly presented to Carmel with many newspaper columns [by Pauline in The Carmelite] of flowery praise. Once could easily become "a big toad in a little puddle" here. Not my intention!" (Daybooks, March 16, 1929, pp. 112-3).

Pauline kept steady tabs on the comings and goings of Weston and various combinations of visiting sons in the pages of The Carmelite. For example she reported on a serious Brett Weston accident while riding with long-time Weston patron and book designer Merle Armitage. Brett suffered a compound fracture when his horse threw him and rolled over onto his leg. ("Personal Bits", by Pauline Schindler, The Carmelite, March 27, 1929, p. 3).

In 1927 Lincoln Steffens and wife Ella Winter came to the U.S. and by chance to Carmel, where Steffens, looking for a quiet place to work on his autobiograohy, decided to settle. They bought a house from the artists Cornelis and Jessie Arms Botke on San Antonio near Ocean, which they called the Getaway. Steffens referred to it as a "refuge for any poor s.o.b. in a jam." They lived there from 1927 to 1936. Typically, having avoided all of his friends by moving to a remote locality, he next invited them all to come visit. Their house became a gathering place for intellectuals far and wide. Robin and Una Jeffers and Edward Weston became their close friends. Winter and Steffens became contributing editors to The Carmelite beginning in 1928. Being used to the excitement of New York, Winter's involvement with The Carmelite made living in "the sticks" bearable. Winter recalls in her 1963 autobiography And Not to Yield , "I became absorbed in the job. I was a journalist at last. It began to take all my time; when Pauline was away I did all her jobs." (For more on Winter and Steffens and Carmel in the 1930s see "Ella Winter: Gallant Fighter" by Connie Wright http://www.carmelresidents.org/News0505.html).

, "I became absorbed in the job. I was a journalist at last. It began to take all my time; when Pauline was away I did all her jobs." (For more on Winter and Steffens and Carmel in the 1930s see "Ella Winter: Gallant Fighter" by Connie Wright http://www.carmelresidents.org/News0505.html).

Ella Winter, 1932. Edward Weston Portrait. Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

Describing Pauline's impact on the village's intelligentsia Winter continued,

"She was the divorced wife of an Austrian architect in Los Angeles she always called Aramess - later I discovered they were his initials, R. M. S. - and she was in many ways the moving spirit of the village...Pauline had to be modern about everything, but in her undifferentiating enthusiasms she sometimes saw further than the rest of us. When her friend Galka Scheyer came in 1928, with pictures by Paul Klee and the Blue Four that people laughed at and wouldn't think of buying, Pauline said Klee could be understood in either poetry or music. She was the first to introduce us to Dada, surrealism, Schoenberg...This "crazy nut" as we thought of her, kept everything at a boil, the sensible and the ridiculous all mixed up. "

"But she's crazy in the best sense," Harry Dickinson maintained; and it must be said that Pauline achieved a good deal. She started our art gallery to show the work of local painters and exceptional photographers, Edward Weston, Edward [Johan] Hagemeyer, Ansel Adams; helped set up a music society that became celebrated, with international artists stopping on their way from Los Angeles to San Francisco to perform in Carmel; and it was Pauline the flibbertigibbet who sparked off our weekly, The Carmelite...The whole village was drawn into The Carmelite's orbit. At studio parties they didn't discuss psychoanalytical plurality or "the inevitable polarity of thought," but the paper, its style and vocabulary, its make-up, illustrations, circulation."

Ironically, Ella Winter would later become an avid collector of the Blue Four after marrying author, screenwriter and fellow communist David Ogden Stewart in 1940 in Hollywood. In a backhanded compliment to Pauline Schindler and Galka Scheyer she wrote in "I Bought a Klee" which appeared in the July 1966 issue of Studio International,

"My relation to Klee had been non-existent. In 1928 a woman had come to the art colony-by-the-sea where I then lived with an exhibition of Die Blau Reiter. We were used in that colony to very modern music, ultra-modern design, avant-garde poetry, but the latest in painting had not yet reached Carmel. I looked at the pictures and with the rest of our jeering art population I'm afraid I jeered. Galka Scheyer, the Swiss woman who brought them, and an old friend of Klee's, tried to explain them, but I don' think it made any impact. She left with as many as she brought."

In January 1929, contributing editor Lincoln Steffens tried to gain control of The Carmelite and turn it over to his wife Ella Winter. Pauline published Steffen's letter to the editor in the January 23rd issue:

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg) A comparison these two mastheads indicates who Steffens' "gang" members might have been. Left is from the December 26, 1928 issue and right is from March 20, 1929. The additions of trusted friends Edward Weston, Galka Scheyer, and Richard Neutra from the Kings Road circle after Steffens' and Winter's departure and financial help from her father gave Pauline the strength to continue publishing for eight more months, maintaining The Carmelite's undeniably high editorial standards and crisp graphic design and modern typography. (See example below).

A comparison these two mastheads indicates who Steffens' "gang" members might have been. Left is from the December 26, 1928 issue and right is from March 20, 1929. The additions of trusted friends Edward Weston, Galka Scheyer, and Richard Neutra from the Kings Road circle after Steffens' and Winter's departure and financial help from her father gave Pauline the strength to continue publishing for eight more months, maintaining The Carmelite's undeniably high editorial standards and crisp graphic design and modern typography. (See example below).

"There are rumors in circulation of a conspiracy...to oust me and my gang from the Carmelite. We are leaving of our own free, mechanistic will. You have always been glad to have us do all the work we would, as long as what we did was up to the high-flying standard you kept mentioning..." Taking exception to her lack of business acumen and flighty editorial style, Steffens continued, "I lifted up my highbrows and thought such an editor would be happier if she had the time to dance and sing and compose music and music criticism unhindered by and unhindering the mere business of journalism..." (Sweeney, p. 105).UPS staff writer Frank H. Bartholomew reported on the controversy which was picked up as far away as Pittsburgh. "The staff of the "Carmelite" has quit en masse, and the blanket resignation includes such prominent names as Fremont Older, Lincoln Steffens, Mrs. Lincoln Steffens (Ella Winter), Charles Erskine Scott Wood and Sara Bard Field. Mrs.Pauline G. Schindler, the publisher, now holds the fort alone." Pauline answered Steffen's above diatribe thusly, "That staff tried harder to acquire the paper than to write for it." ("Dispute Over Carmel Paper Amuses Coast", Pittsburgh Press, February 15, 1929, p. 21).

.jpg)

Lincoln Steffens, Carmel, 1929. Edward Weston portrait from Weston's Westons: Portraits and Nudes by Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. (From my collection). Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

by Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. (From my collection). Collection Center for Creative Photography. ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents.

.jpg)

.jpg) A comparison these two mastheads indicates who Steffens' "gang" members might have been. Left is from the December 26, 1928 issue and right is from March 20, 1929. The additions of trusted friends Edward Weston, Galka Scheyer, and Richard Neutra from the Kings Road circle after Steffens' and Winter's departure and financial help from her father gave Pauline the strength to continue publishing for eight more months, maintaining The Carmelite's undeniably high editorial standards and crisp graphic design and modern typography. (See example below).

A comparison these two mastheads indicates who Steffens' "gang" members might have been. Left is from the December 26, 1928 issue and right is from March 20, 1929. The additions of trusted friends Edward Weston, Galka Scheyer, and Richard Neutra from the Kings Road circle after Steffens' and Winter's departure and financial help from her father gave Pauline the strength to continue publishing for eight more months, maintaining The Carmelite's undeniably high editorial standards and crisp graphic design and modern typography. (See example below).

Announcement for a special issue devoted to modern architecture from the March 20, 1929 issue, p. 6. (From my collection).

A June 12, 1929 entry in Edward Weston's Daybook describes a drive into the valley with "Paul" (Weston's new nickname for Pauline Schindler to her great delight) and dinner with her and Dene Denny and Hazel Watrous. The evening's conversation was on how to run the Carmelite, and its aspirations. Weston wrote,

Weston writes in his January 3, 1929 Daybook entry,

Neutra's choice of Weston to make the American selections provided the entree for him, son Brett and friend and future Group f.64 member Imogen Cunningham (along with Ansel Adams, Willard Van Dyke, and others), to be included in this seminal show alongside the European avant-gardists. The above catalogue as well as the Russian exhib installation were designed by El Lissitzky who also designed Neutra's 1930 book Amerika

member Imogen Cunningham (along with Ansel Adams, Willard Van Dyke, and others), to be included in this seminal show alongside the European avant-gardists. The above catalogue as well as the Russian exhib installation were designed by El Lissitzky who also designed Neutra's 1930 book Amerika (see directly below) which features a 1927 Brett Weston photo of a factory in Los Angeles in El Lissitsky's cover photomontage and internal photos by both Brett and Edward. This was likely the first cover photo Brett had ever had published and it was also published in the Los Angeles Times as part of Athur Millier's review of his first one-man show in July 1930 at Jake Zeitlin's Book Shop. (Millier, Arthur, ""Photographs for Himself," L.A. Times, July 25, 1930, p. III-12).

(see directly below) which features a 1927 Brett Weston photo of a factory in Los Angeles in El Lissitsky's cover photomontage and internal photos by both Brett and Edward. This was likely the first cover photo Brett had ever had published and it was also published in the Los Angeles Times as part of Athur Millier's review of his first one-man show in July 1930 at Jake Zeitlin's Book Shop. (Millier, Arthur, ""Photographs for Himself," L.A. Times, July 25, 1930, p. III-12).

Film und Foto exhibition catalog and poster , 1929, Deutschen Werkbunds, Stuttgart and Willi Ruge poster design. Film und Foto

, 1929, Deutschen Werkbunds, Stuttgart and Willi Ruge poster design. Film und Foto

Right, Manuel Hernandez Galvan, 1924. Edward Weston portrait from above exhibition catalog.

"I, being on the editorial staff, had to listen in until after midnight though bed called me, having retouched all day. Village gossip about the divorce of the Lincoln Steffens and Ella Winter. A letter from Una Jeffers, written on the train, again expressing their pleasure in the portraits. And a catalogue from Film und Foto - Stuttgart (see below): they reproduced my head of Galvan, and published my article, hung 18 of Brett's photographs and 20 of mine. I sent 20 from each of us."Film und Foto was a very important avant-garde traveling exhibition in which Richard Neutra, through his European publishing and Deutscher Werkbund connections, was responsible for America's contributions.

Weston writes in his January 3, 1929 Daybook entry,

"... Neutra is always keenly responsive, and knows whereof he speaks. Representing in America an important exhibit of photography to be held in Germany this summer, he has given me complete charge of collecting the exhibit, choosing the ones whose work I consider worthy of showing, and of writing the catalogue forward to the American group. ... I have busy days ahead." (Weston, pp. 102-3).

Weston wrote in his catalog section introduction "America and Photography",

"I have written of photography as direct, honest, uncompromising, - and so it is when it is used in its purity, if the worker himself is equally sincere and understanding in selection and presentation. Then it has a power and vitality which moves and holds the spectator. There can be no lie in such photography. No human hand of possible frailty has in the recording lessened its pristine beauty, nor misrepresented its meaning, destroying significance."

Neutra's choice of Weston to make the American selections provided the entree for him, son Brett and friend and future Group f.64

Amerika: Die Stilbildung des Neuen Bauens in den Verienigten by Ricard Neutra, Verlag Von Anton Scholl, 1930. 1927 Brett Weston photo of a Los Angeles factory included in the cover photo montage designed by El Lissitzky. From my collection.

by Ricard Neutra, Verlag Von Anton Scholl, 1930. 1927 Brett Weston photo of a Los Angeles factory included in the cover photo montage designed by El Lissitzky. From my collection.

Film und Foto exhibition catalog and poster

Right, Manuel Hernandez Galvan, 1924. Edward Weston portrait from above exhibition catalog.

On September 16th, the Steffens "gang" finally wrested control of The Carmelite from Pauline. The meeting she called to hopefully garner badly needed financial support turned into a palace coup. The September 20 issue of the Carmel Pine Cone reported in an editorial titled "Torn From the Arms of its Mother", "Coolly, almost coldly then, the deal was put through. New papers were drawn, strictly legal: a pen was placed in the shaking hand of Mrs. Pauline Schindler; "Sign on the dotted line," came the command. And Mrs. Schindler signed." The Carmelite folded for good in December 1932. (Sweeney, p. 105).

A September 20, 1929 entry in Weston's Daybook references Pauline's freelance work and a peek into the Carmel social scene she was undoubtedly involved in.

A September 20, 1929 entry in Weston's Daybook references Pauline's freelance work and a peek into the Carmel social scene she was undoubtedly involved in.

"Up at 4:00 and in my darkroom straightening prints from work of yesterday and the day before: work which was strenuous enough to put me to bed at 8:30. At last I have been printing the peppers. I had to have an excuse to do them for conscience's sake, for orders are still behind: the excuse was Pauline's request for several prints for Vogue. But I notice that instead of printing just one, I found it necessary to print five, - for selection! Well, they are gorgeous, - the strongest things I have done, outside of some portraits... A big mask party planned for tomorrow night, which Ramiel [McGehee] is engineering. Over fifty invited from all walks of life: Pebble Beach and Highlands Society to Carmel Bohemians! I am in the excitement only as a spectator: until the night!"

Weston's Daybook entry for October 27, 1929 reads,

"...Dr. and Mrs. Lovell arrived wanting to take Brett and me to a football game. Another day lost, at least for work. Friends arrive here on their vacation, and in vacation moods. One cannot always deny them."This visit occurred just four days after receiving the certificate of occupancy for their new Neutra-designed Health House near Griffith Park in Los Angeles.

PGS left Carmel a short time later but returned to visit often, especially for exhibition openings such as her May 1930 traveling "Contemporary Creative Architecture" show and several of Edward Weston's at the Denny-Watrous Gallery. For example, her review of Weston's July 1931 retrospective exhibition was published in the July 29th issue of The Carmelite indicating that she was still actively participating in Carmel events although no longer officially associated with her old pride and joy. (See the 1946 MOMA exhibition catalogue The Photographs of Edward Weston edited by Nancy Newhall, p. 36).

For a period of years she gravitated between the Theosophist communities of Halcyon and nearby Oceano and Ojai where Mark was in enrolled in the private Ojai Valley School from October 1932 to June 1937. (Sweeney, p. 111). The Schindlers and Neutras were both involved with people associated with the Krotona Institute of Theosophy headquartered in Beachwood Canyon until it moved in 1926 into a complex of buildings near Ojai, California, designed by Robert Stacy-Judd. (Krotona Colony in Hollywood).

Renowned Indian mystic and guru Jiddu Krishnamurti also set up shop for his Order of the Star sect in Ojai the same year where he was visited by wealthy Theosophist supporter J. J. (Koos) van der Leeuw, brother of future Neutra VDL Research House financier C. H. (Kees) van der Leeuw in 1928. (See article below). Koos gave numerous Theosophical lectures around Los Angeles during visits in 1924, 1928 and September 1931. (Los Angeles Times). He could very well have crossed paths with the architect as his Industrialist/Theosophist brother had visited Neutra in Los Angeles during May 1931 to view the Lovell Health House and Neutra's other projects and lecture on "The Future of Modern Factories" at an Electric Club meeting at the Biltmore Hotel. It was likely during this visit that Kees introduced Neutra to Rosalind Rajagopal resulting in a commission for an apartment in Hollywood three years later. (See "Architecture to be theme of Dutch Speaker", L.A. Times, May 18, 1931, p. I-3 and Lives in the Shadow with J. Krishnamurti by Radha Rajagopal Sloss, Bllomsbury, 1991, p. 136. See also Richard Neutra and the California Art Club for more on Kees and Neutra).

Los Angeles Times, May 22, 1928, pp. 1-2. From ProQuest.

Sitting: Nityananda (Krishnamurti's brother), Philip Baron van Pallandt, Krishnamurti, Harold Baillie-Weaver (teacher of Krishnamurti), Count Fabrizio

Ruspoli and Miss. Cornelia Dilkraaf, National Representative of the Association in the Netherlands. Photo taken 09-30-1923. From http://www.landgoedeerde.nl/Krishnamurti.htm

The above group portrait of a 1923 Theosophical get together at Castle Eerde is important as it links the van der Leeuw brothers, Krishnamurti and D. Rajagopal. Rajagopal's wife Rosalind later had an affair with Krishnamurti and commissioned Neutra in 1934 to design a remodel of her apartment in Hollywood. (Discussed in more detail later in this article).

Jiddu Krisnamurti, ca. 1920s. Photographer unknown. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jiddu_Krishnamurti

Pauline lived in Ojai intermittently living in a series of rented cottages. From this base she continued to visit Santa Barbara, Halcyon and the Oceano Dunes settlement of Moy Mell. She also traveled to Santa Fe, the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles. During her periodic stays in Los Angeles she lived briefly on Hillcrest Road and also occasionally stayed at Kings Road for brief stints between the comings and goings of tenants in the guest-studio and/or her wing.

In early 1930 Pauline submitted a six-page article, "Samuel House, Los Angeles, Lloyd Wright, Architect", to Architectural Record which was eventually published in the June 1930 issue. She also submitted photos and an article on the Kings Road House to the same publication which was rejected. This prompted an angry letter of protest from RMS. Oddly, Kings Road, arguably the most iconic modern house in the country would not be published until 1932. (Sheine, p. 261).

PGS authored an article, "The Suburban Home Moves Out of Doors", featuring RMS's furniture designs which was published in the May 1930 issue of The Small Home. Later in the year she had an article published in the highly-regarded literary journal Pagany: A Native Quarterly. Editor Richard Johns frequently featured the work of Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams and many other legendary poets and authors thus Pauline, as was her custom, was keeping famous company indeed.

In early 1930 Pauline submitted a six-page article, "Samuel House, Los Angeles, Lloyd Wright, Architect", to Architectural Record which was eventually published in the June 1930 issue. She also submitted photos and an article on the Kings Road House to the same publication which was rejected. This prompted an angry letter of protest from RMS. Oddly, Kings Road, arguably the most iconic modern house in the country would not be published until 1932. (Sheine, p. 261).

PGS authored an article, "The Suburban Home Moves Out of Doors", featuring RMS's furniture designs which was published in the May 1930 issue of The Small Home. Later in the year she had an article published in the highly-regarded literary journal Pagany: A Native Quarterly. Editor Richard Johns frequently featured the work of Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams and many other legendary poets and authors thus Pauline, as was her custom, was keeping famous company indeed.

In January 1930 Pauline had an article "A Significant Contribution to Culture: The Interior of a Great California Store as an Interpretation of Modern Life" published in California Arts & Architecture. The article described in glowing terms the new Bullock's Wilshire Department Store and the interiors designed by Jock Peters, John Weber and Kem Weber. Of the store she wrote,

PGS was undoubtedly aware of the December 1928 "Decorative and Fine Arts of Today"exhibition seen in the L.A. Times ad above when writng the article. The Bullock's show featured the work of the RMS, Richard Neutra, Kem Weber, Jock Peters, Edward Weston and many others and was organized by Kings Road salon regular and UCLA art teacher, Annita Delano (also in the show) and Eleanor Lemaire for Bullock's Department Store's downtown Los Angeles location while Bullock's Wilshire was under construction. (For much more on this exhibition see my "Foundations of Los Angeles Modernism").

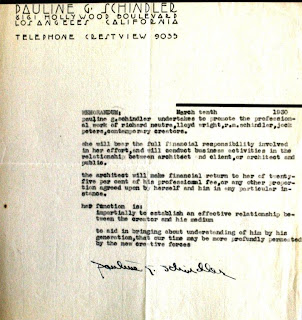

Delano's Bullock's exhibition was undoubtedly the genesis for Pauline's March 1930 decision to organize and curate a traveling exhibition of Contemporary Creative Architecture in California (see above announcement) featuring Frank Lloyd Wright, Richard Neutra, R. M. Schindler, Jock D. Peters, John Weber, Kem Weber and J. R. Davidson for the Western Association of Museum Directors, write a book featuring their work and act as their agent for booking lectures (see agent contract below). Nothing ever came of the book project. (McCoy, p. 58).

"It constitutes an unmistakable advance in the movement of contemporary design. Much of its effect is due to color and light; and it must be actually seen for its artistic significance to be realized. Not one or two, but a number of different persons worked together in creating this extended and complicated series of compositions, which constitutes a small village off specialty shops."

Los Angeles Times, December 9, 1928, p. III-23. From ProQuest.