Josef von Sternberg from The Films of Josef von Sternberg by Andrew Sarris, Museum of Modern Art, 1966, frontispiece.

by Andrew Sarris, Museum of Modern Art, 1966, frontispiece.

This is the interwoven story of two of Richard Neutra's more important commissions, i.e., movie director Josef von Sternberg's house in Northridge and fellow movie director Dudley Murphy's Holiday House Motel in Malibu. (See above and below). Neutra and his circle's involvement with the California Art Club also played a significant role in eventually landing these plum projects. Neutra's dynamic energy and focus, penchant for global self-promotion, and resoluteness in the search for clients to survive the Great Depression and to begin to build his legacy resulted in an ever-growing orbit of important friends, acquaintances, contacts and colleagues. Former partner and landlord R. M. Schindler and his wife Pauline were most important to the development of Neutra's personal network as Richard, Dione and baby Frank were welcomed as tenants at Kings Road on March 7, 1925. They remained until May 1930 when Neutra embarked on his all-important career-building world tour.

The Schindler's coterie of intelligentsia and California Art Club-affiliated avant-garde artists automatically became the Neutras' as anyone who has visited the intimate surroundings at Kings Road will understand. Dione wrote her mother in September 1925, "We are slowly drawn into the whirl of social activities, although we are only starting to make acquaintances..." (From Richard Neutra: Promise & Fulfillment, 1919-1932

The Schindlers' relationship with Aline Barnsdall, Pauline as one of Aline's kindergarten teachers (with her husband's future client Leah Lovell) and RMS as her post-Frank Lloyd Wright architect, also plays an important part in this story. (See also PGS). Aline donated her Frank Lloyd Wright-designed and R. M. Schindler-supervised Hollyhock House and surrounding compound to the City of Los Angeles in 1926 with the provision that the California Art Club be granted a 15-year lease to use Hollyhock as a clubhouse and gallery space. (See below).

Conrad Buff self-portrait. From The Art & Life of Conrad Buff, by Will South, George Stern Fine Arts, 2000, p. 45, hereinafter Buff.

by Will South, George Stern Fine Arts, 2000, p. 45, hereinafter Buff.

Shortly after moving into Kings Road the Neutra's met artists Conrad and Mary Buff (see above and below) through the Schindler salons. The Buff's had met the Schindlers soon after their Kings Road house was completed in 1922, likely through salon attendee Edward Weston who had a studio in Tropico near their home in Eagle Rock and for whom Mary modeled the same year. (See below). Weston's sons Neil and Cole also attended Aline Barnsdall's kindergarten class where Pauline Schindler and future Schindler and Neutra client Leah Lovell taught.

Mary Marsh Buff by Edward Weston, 1922. (From The Art & Life of Conrad Buff, by Will South, George Stern Fine Arts, 2000, p. 45 hereinafter Buff).

by Will South, George Stern Fine Arts, 2000, p. 45 hereinafter Buff).

The Buffs then quickly became friends with Schindler tenants Karl and Edith Howenstein. One of RMS's first friends after he moved to Chicago in 1914, Karl Howenstein was employed at the Art Institute of Chicago after a brief stint working for Louis Sullivan. (See my R. M. Schindler, Richard Neutra and Louis Sullivan's "Kindergarten Chats" for more details). After the Schindlers moved to Los Angeles in 1920 to work on Frank Lloyd Wright's Hollyhock House for Aline Barnsdall, the Howensteins followed in 1922 where Karl took a position at the Otis Art Institute. They moved into the Schindler's Kings Road House for about two years between 1922 and 1924.

Thanksgiving at Kings Road, 1923. Clockwise around the table from left, Dorothy Gibling (Pauline's sister), Betty and A. R. Brandner, obscured, Max Pons, Herman Sachs (back center), Karl Howenstein (far right), Edith Howenstein, Anton Martin Feller, E. Clare Schooler, and unidentified. Not shown, the Schindlers Photo by R. M. Schindler. From "Life at Kings Road: As It Was 1920-1940" by Robert Sweeney in The Architecture of R. M. Schindler, p. 97

Buff spoke of the Howensteins (see above far right) in his Oral History,

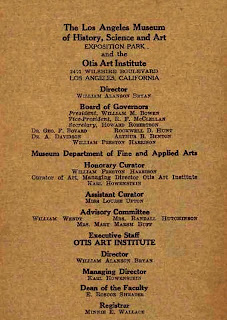

"One of the friends that we got acquainted with was a man by the name of [Karl] Howenstein. He came from Chicago, and he and his wife were quite progressive minded, he was all for modem art and at the same time he was a Freudian. He was interested in psychoanalysis, and together with modern art and talks on psychoanalysis he captivated us, and we became quite good friends." (Conrad Buff Oral History Transcript, p. 122, hereafter CB)Howenstein would go on to become Managing Director of the Otis Art Institute which was housed in the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art building and which also had numerous California Art Club members on the faculty. The 1923-24 Otis Catalogue seen below lists both Mary Marsh Buff and William Wendt, a founding member and early president of the California Art Club, on the Advisory Committee. The president of the California Art Club, E. Roscoe Shrader was also Dean of Faculty at Otis between 1922 and 1949. (For more on Howenstein's background and his indirect influence on Harwell Hamilton Harris's career choice see Mod).

The Otis Art Institute of the Los Angeles Museum of History Science and Art 1923-1924 Catalogue. From Otis College Online.

Buff stated in his oral history,

"About 1922, I joined the California Art Club. The California Art Club in those days was practically the only club in Los Angeles that represented the artists. They had a yearly show at the Los Angeles Museum [of History, Science and Art], that was a privilege they had, and it was quite the show of the year, although there was another exhibition that took place in the fall where everybody was eligible to submit their works to a jury. In those days, the museum was really a place where the artists were treated royally, not like now where everybody has to send pictures in and submit them to a jury and be perhaps in competition with ten thousand others. In those days, the museum would come to your house, pick up the pictures, and submit them to the jury. Practically everybody that had half-way decent work would be accepted. After the show was over, the museum would bring the pictures back. So it was a golden age for the artists.

In the middle '20's or the later '20s, the club had a wonderful opportunity. Miss Barnsdall of Barnsdall Hill gave her residence to the club, to be solely used by the club. I don't know why Miss Barnsdall didn't like her house, although at this time it was considered the most beautiful building in Los Angeles. It was, of course designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and the supervising architect was Rudolph Schindler; as I said, it was quite a remarkable building and everybody liked it except the other architects. The architects were down on Frank Lloyd Wright. We were very fortunate in having this privilege of using the building for fifteen years. She gave us a fifteen-year lease on the building."

Aerial view of Olive Hill-Barnsdall Park with Aline Barnsdall's Frank Lloyd Wright and R. M. Schindler designed Hollyhock House compound. From the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

Interior view of Aline Barnsdall's recently donated Hollyhock House from the February 1927 issue of the California Art Club Bulletin.

Los Angeles Times Art Critic, etcher and California Art Club member Arthur Millier. Photo by Johan Hagemeyer, life-long friend of Edward Weston. (Weston rented Hagemeyer's Carmel studio when he first moved there in 1929. For much more on Hagemeyer see PGS). Image courtesy Museums and the Online Archive of California.

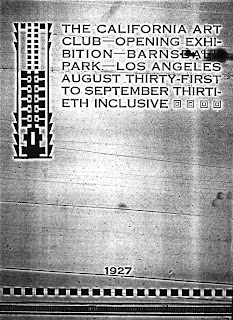

Schindler and Neutra friend Kem Weber led a team of CAC members including Frederick Monhoff, Edouard Vysekal, Los Angeles Times art critic Arthur Millier (see above) and others in "designing and providing the special requisites for conversion of [Hollyhock House's] future uses in the cause of art." ("Art Magazines in East Hear of Clubhouse Here," Los Angeles Times, March 24, 1927, p. I-5). The Club held its formal opening and inaugural exhibition on Olive Hill beginning on August 31, 1927 featuring 225 works by many "ecstatic artists" in the Schindler-Neutra circle including Edward, Brett and Chandler Weston, Conrad Buff, Annita Delano and undoubtedly many others. ("Art Club Takes Over New Home," Los Angeles Times, September 1, 1927, p. I-1). Weston wrote in his Daybooks of the opening,

"[Margrethe Mather] came to choose prints for the photographic exhibition in connection with the formal opening of the new Calif. Art Club house, Olive Hill, Hollywood. (See below). Three of Brett's photographs will be hung, four of mine, and one of Chandler's." (The Daybooks of Edward Weston, Vol. II, California, p. 38). (For more on the Westons and Buff see PGS and for more on Delano see "Foundations of Los Angeles Modernism: Richard Neutra's Mod Squad" hereinafter referred to as Mod).)

Hollyhock House, 1927 (new home of the California Art Club). Margrethe Mather photograph. From Margrethe Mather & Edward Weston: A Passionate Collaboration by Beth Gates Warren, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2001, p. 120. Courtesy Getty Research Institute Special Collections.

Catalog for the inaugural California Art Club exhibition at their new clubhouse at Barnsdall Park, August 1927. From the Annita Delano Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian, microfilm roll 3000).

Aline Barnsdall European Poster Exhibition, Barnsdall Park, September 1927 designed by R. M. Schindler. From The Oilman's Daughter by Norman M. Karasick & Dorothy K. Karasick.

by Norman M. Karasick & Dorothy K. Karasick.

Los Angeles Times, August 27, 1927, p. I-11. From ProQuest.

One of the features of the month-long opening exhibitions was a showing of 64 European travel and advertising posters collected by Barnsdall in her latest travels. (See above). She commissioned Schindler to design the distinctive outdoor display panels seen in the above photo and in two photos in a review in the Times a few days later. ("Barnsdall Park - A City Cultural Center," Los Angeles Times, September 4, 1927, p. I-6). Schindler was likely working on the installation about the time Pauline packed up son Mark and left Kings Road sometime in August after some protracted marital difficulties likely related to RMS's philandering ways. Conrad Buff recalled Schindler's infidelity,

"Schindler had built a house on Kings Road. Schindler, besides being a disciple of Frank Lloyd Wright, was a very handsome fellow. He was quite a ladies' man, and part of his business was to make love to all the ladies he could. He had a very interesting wife, but that didn't bother him. There was quite a group of people that used to meet down at Schindler's house." (Buff, p. 123).This was also the same month Philip Lovell commissioned Neutra to begin design on his Health House near Griffith Park. In the spring of 1928 Lovell also chose Neutra over Schindler to design his Physical Culture Center at 154 W. 12th St. in downtown Los Angeles which entailed remodeling over 5,000 sq. ft. of industrial space. ("Four Leases Completed by Company Here," Los Angeles Times, February 5, 1928, p. V-6). (For much more detail see PGS).

Lovell Physical Culture Center, Los Angeles, 1928, Richard Neutra, architect. From Picnic de Pioneros by Ruben Alcolea, p. 178.

Lovell Pysical Culture Center, Los Angeles, 1928, Richard Neutra, architect. From Richard Neutra and the Search for Modern Architecture by Thomas S. Hines, p. 78.

by Thomas S. Hines, p. 78.

Lovell ad which ran in the Los Angeles Times throughout 1928.

Shortly after the CAC inaugural festivities Conrad Buff also commissioned Neutra to design his garage and studio entrance at 1225 Linda Rosa in Eagle Rock. (See below and Buff, p. 124-5). The building permit for same was issued on January 30, 1928 thus this was quite a busy period for Neutra with three concurrent projects on the boards.

Entrance, Studio of Conrad Buff, Los Angels, R. J. Neutra, Architect. Photos by Willard D. Morgan. From Picnic de Pioneros by Ruben Alcolea, p. 184.

Entrance, Studio of Conrad Buff, Los Angels, R. J. Neutra, Architect. Photos by Willard D. Morgan. Architectural Record, November, 1930 , p. 438. (From my collection).

, p. 438. (From my collection).

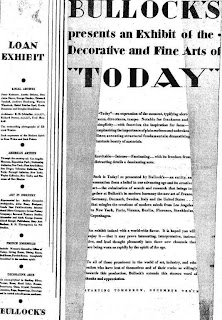

Neutra spent all of 1928 working feverishly on the Lovell Health House design and all of 1929 overseeing its construction. Neutra's name is first mentioned in association with the CAC in the September 1928 issue of the CAC Bulletin announcing his inclusion along with Kings Road salon habitues and CAC members R. M. Schindler, Jock Peters, Kem Weber, Edward Weston, Annita Delano, Henrietta Shore, Edouard Vysekal, George Stanley, and Frederick Monhoff in the December exhibition "Decorative and Fine Arts of Today" at Bullock's Department Store curated by Delano. (This period is covered in much detail in both my PGS and Mod). Many of this group were also working on the interiors of the new Bullock's Wilshire store then under construction. Of the trend towards modernism in design L. A. Times art critic Arthur Millier wrote,

"Following the lead of similar exhibitions in New York and other large cities, this is in the nature of an experiment in which the local public's pulse will be felt. ... [including] fine art, craft work and architectural exhibits from those artists of Southern California who are working in the modern spirit of simple, sensitive design." (Millier, Arthur, "Decorative Art of Today," L.A. Times, December 9, 1928, p. III-13).

Exhibition announcement, L.A. Times, December 9, 1928, p. III-23. From ProQuest.

Delano included in the exhibition: 15 Edward Weston photographs, paintings, drawings and sculpture from Peter Krasnow, two or her own watercolors, eight lithographs and paintings from Henrietta Shore, Kem Weber designs for an entrance hall, dining room, bedroom and bathroom, sculpture by George Stanley, R. M. Schindler's Wolfe House on Catalina Island, Lovell Beach House in Newport Beach, and 3 other projects, five interiors designed by Jock Peters, drawings and watercolors by Edouard Vysekal, architectural designs by Fred Monhoff, Richard Neutra's Rush City railroad terminal, office and store building and Metropolitan Business District and more by others.

A follow-up "Modern Arts" exhibition sponsored by the Los Angeles Architectural Club, likely also curated by Delano, featured many of the same CAC members such as Kem Weber, Richard Neutra, R. M. Schindler, Conrad Buff, George Stanley, Feil & Paradise and J. R. Davidson and took place at the Architect's Building at 5th and Figueroa. ("Modern Design to be Architect's Subject," Los Angeles Times, March 18, 1929).

California Art Club guest book entries, May 4-9, 1928 courtesy of Eric Merrell, current CAC historian. I highly recommend his Siqueiros in Los Angeles and His Collaborations with the California Art Club for more detailed information.

Like his friend Conrad Buff, Neutra presciently viewed CAC membership as a possible entree to potential clients. Ferenz likely joined to make similar contacts for future gallery exhibitions and attract more students to his Academy. Ferenz, already a frequent CAC visitor, had previously viewed the Vysekal's exhibition at the CAC on May 6, 1928, likely prompted by Millier's same day review. (See above and Millier, A., "Vysekals in Full Showing," Los Angeles Times, May 6, p. IV-30).

The Aristocracy of Art by Merle Armitage, Jake Zeitlin, 1929. From my collection.

Neutra and Schindler participated in a debate "Modern versus Classical Style" at the Club on February 18, 1929 against the team of Vincent Palmer and Vernon McClurg. ("Architects to Debate Styles This Evening," Los Angeles Times, February 18, p. I-5). A month after Neutra joined the CAC, he and friend Buff were elected officers. Neutra was elected second vice-president while Buff became recording secretary for the year beginning April 1st. ("Art Club Names New Officers and Director," Los Angeles Times, March 24, 1929, p. IV-8 and letterhead below). Jake Zeitlin crony, Schindler salon regular and Weston patron Merle Armitage lectured at the Club on "The Aristocracy of Art" on March 4, 1929. (See above and below). Ferenz lectured at the Club shortly after signing up on the topic "What is Modern Art?" and again in June as part of a panel discussion on, "Does Thrift Cripple the Imagination?" ("Ferenz Will Lecture at Art Club's Forum," Los Angeles Times, March 25, 1929, p. I-18 and "Symposium Arranged," Los Angeles Times, June 17, 1929, p. I-3).

Will Connell portrait of early Weston supporters Merle Armitage and Jake Zeitlin, ca. 1930. (From L.A.'s Early Moderns , p. 45).

, p. 45).

California Art Club letterhead, 1929. From the Annita Delano Papers, Archives of American Art. (For more on the Delano-Neutra relationship, see Mod).

Neutra was quickly accepted as a member of importance evidenced by his selection, along with Club President E. Roscoe Shrader, Kem Weber, and L.A. Times art critic Arthur Millier, to a jury to choose a winner from a design competition for a mural decoration to be installed in the south alcove of California Art Club Hollyhock House living room and west wall of the music room. (California Art Club Bulletin, February 1929, cover).

Galka Scheyer at Kings Road, circa 1931. (From "Life at Kings Road: As It Was 1920-1940" by Robert Sweeney, p. 108 in the 2001 MOCA exhibition catalog The Architecture of R. M. Schindler).

Galka Scheyer, (see above) promoter of The Blue Four, was a fellow Kings Road tenant with the Neutras during the summer of 1927 witnessing Pauline's departure and helping broker the Lovell Health House commission for Neutra. She also played an important indirect role in Neutra's von Sternberg commission. Academy of Modern Art founder, F. K. Ferenz, UCLA art professor and CAC member Annita Delano and Mexican muralists Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros were also key figures linked to Neutra's von Sternberg and Dudley Murphy commissions. (For much more on Ferenz, Delano and Scheyer see Mod and for more on Siqueiros see PGS).

Von Sternberg became a large blip on Galka Scheyer's radar screen sometime in 1929 when she learned of his purchase of 18 pieces from the Braxton Gallery during the Archipenko exhibit of May 1929 possibly through her close friend Gela Archipenko. ("Archipenko Takes Here," Los Angeles Times, May 26, 1929, p. 16). In an April 26 letter to Kandinsky in Dessau Scheyer wrote,

"...[Alexander] Archipenko, who we wanted to exhibit while waiting for the modern museum, has meanwhile sold 16 works via an art dealer in Hollywood to a von Sternberg, a movie person. I contacted him (Harry Braxton) immediately; he is coming here and is interested in the Blue Four. If something comes of that...I will telegram." (Galka E. Scheyer and the Blue Four Correspondence, 1924-1945edited by isabel Wunche, p. 163-4).

Von Sternberg, sufficiently wealthy by now to buy whatever he pleased, patronized the art dealers who serviced the Hollywood community such as Harry Braxton and also attended local shows and meetings of the California Art Club as did Kings Road habitue and fellow movie director and art collector Dudley Murphy. Since the artwork he was interested in was often controversial, many of the shows took place in private homes such as the Schindler's Kings Road House and fellow circle members Sam and Harriet Freeman's Frank Lloyd Wright-designed house and the home of Walter and Louise Arensberg or in bookshops, in particular those of Jake Zeitlin and Stanley Rose.

An agent without a gallery, the shrewd Scheyer was eager to associate with Braxton's establishment, as she had with the Oakland Art Gallery in the Bay Area, to both mount exhibitions of the Blue Four and other avant-garde artists and to gain entree into Hollywood's elite emigre circle, especially von Sternberg. Scheyer and Braxton hammered out the details for a long-term collaboration in May in San Francisco right after his Archipenko show and she convinced him to move to a more desirable location. (Galka E. Scheyer and the Blue Four Correspondence, 1924-1945

In a June 4th collective letter to the Blue Four Scheyer excitedly wrote of the Braxton events,

"I will explain in telegraphic shorthand because I have absolutely no time to write in detail. My telegraphic style will be so mathematically clear that you will drink a bottle of champagne in honor of the "Blue Four"

Hollywood ... an art dealer . . . rich film people ... Archipcnko sold 18 works before the opening ... Name of art dealer Braxton ... has been in Hollywood for 6 month, (from New York), was here on the 25th of May (with wife) ... Both wildly enthusiastic ... and appreciative. Result: September 1- 15, Jawlensky exhibition ... September 15 - October 1, Kandinsky, October 1- 15, Feininger, October I5 - November 1, Klee.

Engaged for 4 lectures at $100 each. Big contract with the notary, Mr. Clapp, director of the Oakland Museum, mme. Scheyer, and Mr. Braxton.

Farewell San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley. Hello Hollywood (Will I end up a movie star after all?). I am just about to pack up and move south." (Scheyer, p. 166).

Scheyer moved in with Pauline Schindler at Frank Lloyd Wright's Storer House at 8161 Hollywood Blvd. upon her return to Hollywood. Pauline had also recently moved back to Los Angeles after a few years in Carmel as editor and publisher of the Carmelite after leaving Kings Road. As was her penchant, she was continuing to promote modernism in all its facets including allowing Brett Weston to open his first professional photography studio on the second floor. (See PGS for more details).

Scheyer probably became acquainted with Braxton through Archipenko's wife Gela and/or her Schindler salon connection with CAC member and Times art critic Arthur Millier. Galka and Gela were frequent traveling companions. They came to Los Angeles together in 1925 where they first met Schindler, Neutra and Herman Sachs. (For more on this see Mod). They also traveled throughout Bali together collecting art during 1931. Scheyer recommended Schindler to Braxton for the design of his new gallery (see below) and a year earlier also recommended him to Director William H. Clapp for the design of a new Oakland Art Gallery which was never built.

Hollywood Brown Derby Restaurant Building, 1620-28 N. Vine St., Hollywood, Carl Jules Weyl, architect, 1928. Note the Hollywood Brown Derby space at the left and the Braxton Gallery space just to the right of the center car. (From flicker).

Braxton and Scheyer wanted a high-profile location and found it in a brand new commercial building (see above) designed and constructed as a 2-story shop, studio and restaurant building for Cecile B. Demille's Vine Street Holding Company. DeMille's original restaurant lease was signed with the Brown Derby Restaurant Company which immediately created a watering hole for Hollywood's elite. ("Store, Studio and Restaurant Building, Hollywood," Southwest Builder & Contractor, June 29, 1928, p. 57). The above photo looking east across Vine Street is how the building appeared before the restaurant opened on Valentine's Day, 1929 and the Braxton Gallery the following September.

Braxton Gallery presentation drawing, front elevation. (From "Braxton Gallery, 1928-1929, Hollywood" by Naomi Sawelson-Gorse in The Furniture of R. M. Schindler , UCSB, p. 87).

, UCSB, p. 87).

Braxton Gallery presentation drawing, floor plan. (From "Braxton Gallery, 1928-1929, Hollywood" by Naomi Sawelson-Gorse in The Furniture of R. M. Schindler, UCSB, p. 86).

Galka collaborated on Braxton's gallery design (see above illustrations) and helped plan the initial exhibitions in the new space. (See "Braxton Gallery, 1928-1929, Hollywood" by Naomi Sawelson-Gorse in The Furniture of R. M. Schindler

Harry Braxton Gallery, 1624 N. Vine, Hollywood, R. M. Schindler, 1929. Viroque Baker photos. (From Sheine, p. 144). Note the Schindler-designed Braxton Chair in the right photo.

Von Sternberg previewed and purchased some of the Blue Four's work from Scheyer before leaving for Europe the previous fall prompting Scheyer to write her clients to coordinate the pricing of their work in case the ravenous collector von Sternberg approached them directly. The highly egotistical von Sternberg often commissioned likenesses of himself for his collection and modeled on the set of "The Blue Angel" for German avant-garde sculptor Rudolf Belling who had a large one-man show in Berlin during filming. Belling's abstract bronze bust (see above) was shipped to von Sternberg about the time the Braxton Gallery "Blue Four" shows were wrapping up. ("Screen director's Metal Bust Unique," Los Angeles Times, April 21, 1930, p. I-2).

Braxton and Scheyer substituted CAC member and Schindler salon regular Peter Krasnow, whom von Sternberg had also collected, for the inaugural September 1929 show which included seven of his carved wood reliefs. (Scheyer, pp. 170-174). Schindler and Neutra had recently collaborated with Krasnow on the design of a major commission for a ceremonial cabinet for Temple Emmanuel-El San Francisco described in a July 28, 1929 L.A. Times article "Krasnow's Work Shown" as "an unusual thing of wood and glass which houses vestments and religious objects." Krasnow carved the panels which were applied to the sides of the chest. Close friend Edward Weston was shown the chest in December 1928, shortly before joining Pauline Schindler in Carmel, after which he wrote in his Daybook, "I take my hat off to you Peter, for a superb piece of work both in conception and technical execution. Tears came to my eyes,..." (Weston, p. 98).

Braxton and Scheyer substituted CAC member and Schindler salon regular Peter Krasnow, whom von Sternberg had also collected, for the inaugural September 1929 show which included seven of his carved wood reliefs. (Scheyer, pp. 170-174). Schindler and Neutra had recently collaborated with Krasnow on the design of a major commission for a ceremonial cabinet for Temple Emmanuel-El San Francisco described in a July 28, 1929 L.A. Times article "Krasnow's Work Shown" as "an unusual thing of wood and glass which houses vestments and religious objects." Krasnow carved the panels which were applied to the sides of the chest. Close friend Edward Weston was shown the chest in December 1928, shortly before joining Pauline Schindler in Carmel, after which he wrote in his Daybook, "I take my hat off to you Peter, for a superb piece of work both in conception and technical execution. Tears came to my eyes,..." (Weston, p. 98).

Scheyer also likely encouraged Schindler to approach von Sternberg directly in an attempt to interest him in a commission for a new house knowing they would meet at the opening of the Blue Four exhibitions at the new Braxton Gallery. While Neutra was preoccupied with overseeing construction of the Lovell Health House and he was designing the new Braxton Gallery space, Schindler wrote to von Sternberg,

Schindler's attempt at self-promotion proved unsuccessful in the von Sternberg case. Little did he know at the time that five years later, the famed director would commission instead his erstwhile partner Neutra to design the modern country house which would become recognized as one of his best works."The movie director who wants to create thorobreds can do nothing but wait until the public grows eyes. The architect who is limited by economic considerations, might thru some chance find a client who already has eyes. I, a pupil of Otto Wagner, of Vienna, have been trying to develop contemporary building in Los Angeles for the last eight years, without finding anyone whose imagination could follow me to the end. Miss Barnsdall who has appreciated my schemes for translucent space architecture, has so far used me to build half-breeds. You are reputed to be a contemporary artist of imagination and achievement. May I present to you a new conception of architecture, which transcends the childish freaks of the fashionable modernique decorator?" (R. M. Schindler to Josef von Sternberg, June 10, 1929, Architecture and Design Collection, UC Santa Barbara).

Neutra finally completed the Lovell Health House (see above and below) in December 1929 to much fanfare in the Los Angeles Times. Dr. Lovell's weekly column described the "Home Built for Health" in much detail including directions to 4616 Dundee Dr. in Los Feliz near Griffith Park for two successive weekends of open house tours to be conducted by Neutra himself. (Lovell, Philip M., "Care of the Body," Los Angeles Times, December 15, 1929, pp. VI-26-27). Neutra soon thereafter began planning his world tour and CIAM conference attendance. He feverishly sent off Art Club member Willard D. Morgan photos of his masterpiece and previous work to a legion of New York and overseas editors and authors of books on modern architecture in shrewdly planning that publication would precede his visitations, CIAM conference attendance and hoped for lectures. (For more on this see Mod).

Neutra and his pride and joy. From the Los Angeles Public Library photo collection.

Neutra's strategy was successful for the most part as articles appeared in Architectural Record (7 pp. with 7 Morgan photos and floor plans), Das Neue Frankfurt, Die Form, Stavba, Cahiers d'Art, and others and in influential books such as Herbert Hoffmann's Die Neue Raumkunst in Europa und Amerika, Sheldon Cheney's The New World Architecture , and Bruno Taut's Modern Architecture

, and Bruno Taut's Modern Architecture , not to mention his own book Amerika: Die Stilbildung des Neuen Bauens in den Verienigten

, not to mention his own book Amerika: Die Stilbildung des Neuen Bauens in den Verienigten to add to his well-received 1927 pre-Lovell effort Wie Baut Amerika?

to add to his well-received 1927 pre-Lovell effort Wie Baut Amerika?

Exhibition Poster for "Contemporary Creative Architecture of California", UCLA April 21-29. Courtesy of the UC-Santa Barbara, University Art Museum, Architecture and Design Collections, R. M. Schindler Collection.

In early 1930 Pauline Schindler organized and curated a traveling exhibition of Contemporary Creative Architects of California featuring the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, Richard Neutra, R. M. Schindler, Jock D. Peters, John Weber, Kem Weber and J. R. Davidson. (See announcement above). The exhibition was on display at UCLA from April 21-29, 1930 and the related Symposium featuring CAC members Richard Neutra, R. M. Schindler and Kem Weber took place on April 27th. CAC member and UCLA art department faculty member Annita Delano likely had much to do with arranging the opening venue for the exhibition. The same show minus Wright, who objected to his erstwhile disciples piggybacking on his fame, also traveled to the CAC clubhouse at Barnsdall Park after Neutra's departure in June (see announcement below) before traveling the Western Art Museum circuit to the Honolulu Academy of Fine Arts, the Henry Art Gallery at the University of Washington in Seattle, The Portland Art Association and the San Diego Fine Arts Gallery. (R. M. Schindler

"Contemporary Creative Architecture of California" Exhibition announcement designed by Pauline Schindler, 1930. Courtesy of the UC-Santa Barbara, University Art Museum, Architecture and Design Collections, R. M. Schindler Collection.

Ad for Weston Exhibition at the Braxton Gallery, Los Angeles Times, February 2, 1930, p. II-18.

Braxton and Scheyer's second show in the new Vine Street gallery was an exhibition of Edward Weston photographs (see announcement above) of which Millier wrote, "At Braxton's we see Weston sharpening the single eye of his camera to exact from nature the minutest details barely visible to the human eye. His approach to art is by way of absolute realism, realism such as should commend itself to the most hide-bound academician." (Millier, Arthur, "Realism or Abstraction," Los Angeles Times, February 9, 1930, p. II-17). Weston had a concurrent show open February 8th at the Denny-Watrous Gallery in Carmel.

The Blue Four Exhibition Catalogue, Braxton Gallery, Hollywood, March-May, 1930. Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute, Peg Weiss Papers.

It is highly likely that Neutra attended the March and April 1930 Braxton Gallery openings for the Blue Four exhibitions seems almost a certainty that he met von Sternberg at same. He also likely learned of von Sternberg's soon to be released movie The Blue Angel about this time.

During Lyonel Feininger's April Braxton Gallery exhibition, the California Art Club honored Mexican painter and muralist Jose Clemente Orozco, his Pomona College mural assistant Jorge Juan Crespo de la Serna and art critic and historian, Professor Jose Pijoan at their monthly dinner meeting on April 17th. ("Notable Company to Meet," Los Angeles Times, April 16, 1930, p. I-8). Club Second Vice-President Neutra most likely attended this meeting and met Orozco since he was slated to be the following month's honoree shortly before his world tour departure. (See below).

Los Angeles Times, May 15, 1930, p. I-8. From ProQuest.

In late May, knowing they would never return to Kings Road, Richard and Dione packed their meager belongings and archives and moved out to begin their long journey. The Buff's allowed them to store their boxes in the previously-mentioned garage Neutra designed for their house in Eagle Rock for the duration of the trip. Dione headed directly to Europe with young Frank and Dion in tow to stay with relatives while Richard set sail for Japan to reconnect with his Japanese architect friends he met during his brief apprenticeship at Wright's Taliesin

Edward Weston had befriended Orozco and Diego Rivera during his three-year sojourn to Mexico with Tina Modotti and wrote of them frequently in his Daybooks . He undoubtedly shared photos of his Mexican work with Neutra during various get togethers at Kings Road. For example Weston wrote in his January 3, 1929 Daybook entry,

. He undoubtedly shared photos of his Mexican work with Neutra during various get togethers at Kings Road. For example Weston wrote in his January 3, 1929 Daybook entry,

"To Richard Neutra's [Kings Road] for supper: other guests were Mr. and Mrs. J. R. Davidson, and [future Schindler client] Dr. Alexander Kaun and wife. Dr. Kaun I met years ago at Margrethe's, but only casually. I like Richard so much, and found Kaun and the others stimulating, so the evening was a rare gathering I do not regret. Even the showing of my work was not the usual boresome task. I felt such a genuine attitude. Neutra is always keenly responsive, and knows whereof he speaks. Representing in America an important exhibit of photography [Film und Foto] to be held in Germany this summer, he has given me complete charge of collecting the exhibit, choosing the ones whose work I consider worthy of showing, and of writing the catalogue forward to the American group. ... I have busy days ahead." (Weston, pp. 102-3 and for more on Alexander Kaun and Film und Foto see PGS).

Orozco, Jose Clemente, "Jose Pijoan, ca. 1940. From Christie's.

Orozco had arrived in Los Angeles on March 22, 1930 to execute a mural at Pomona College's new Frary Dining Hall through a commission arranged by Professor Jose Pijoan (see above), then teaching at Pomona, and fellow Mexican artist Jorge Juan Crespo de la Serna, then teaching at Chouinard Art Institute and creative design and painting at Ferenz's Academy of Modern Art. In a dialogue with Frary Hall architect Sumner Spaulding, Pijoan convinced him that a mural would be a fitting decoration and originally wanted Diego Rivera to perform the work. Crespo convinced Pijoan that Orozco would be better for the job. Arrangements were made to bring Orozco to the West Coast from New York to complete the massive Prometheus fresco. (See below).

Prometheus by Jose Clemente Orozco, 1930, Frary Dining Hall, Pomona College. Image from Claremont Heritage. See the following link for a photograph of Orozco at a gathering in the Dining Hall after completion of the mural from the Harold Mudd Library Special Collections.

Weston first became favorably aware of Orozco and his work in late 1925. On May 2, 1926 mutual friend Anita Brenner brought Weston to Orozco's studio in Coyoacan to introduce the photographer to the man and his work. The next day Brenner took Orozco to Weston's studio to return the favor. Weston wrote of the meetings,

"Sunday, Anita and I went to Coyoacan for a visit with Orozco the painter. I had hardly known his work before, which I found fine and strong. His cartoons - splendid drawings, in which he spared no one, neither capitalist nor revolutionary leader - were scathing satires, quite as helpful in destroying a "cause," heroes and villains alike, as a machine gun. I would place Orozco among the first four or five painters in Mexico, perhaps higher. Monday eve he came to see my work. I have no complaint over his response. I wish I had known him sooner, - now it is almost too late." (The Daybooks of Edward Weston, I. Mexico, p. 158).

Brett Weston photo of Prometheus by Jose Clemente Orozco. (Millier, A., "Orozco's Fresco Complete," Los Angeles Times, July 6, 1930, pp. II-7, 12.

Brett Weston, who was in Mexico with Edward during the Orozco studio visit, photographed Prometheus upon its completion with the above image illustrating Arthur Millier's highly favorable review of the work. At the time Brett's studio was on the ground floor of Frank Lloyd Wright's Storer House which he was subletting from Pauline Schindler and also sharing rooms with fellow tenant Galka Scheyer, recently relocated from the Bay Area to hopefully develop a client base around the Braxton Gallery shows. Orozco was scheduled for an exhibition at the Braxton Gallery in September and Pauline also conducted private viewings of Brett's work there for prospective collectors. ("Orozco to Put Murals in College," Los Angeles Times, March 21, 1930, p. I-9).

After completing Prometheus Orozco spent the summer months in San Francisco where he painted a number of canvasses in preparation for a large touring exhibition, Mexican Arts, which opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York later that year. While in San Francisco, he and his dealer Alma Reed paid a visit to Weston in Carmel. Of this Edward wrote,

"July 21. The coming of Clemente Orozco and Alma Reed will go down as an important day in my personal history. I am to open the season with a one-man exhibit in Alma Reed's New York Gallery: but more important she is to keep my work, feature it along with Orozco's, to the exclusion of all other artists.' ... Around the grate fire Saturday night I showed my work. Orozco had not seen it since Mexico. ... Alma Reed asked "When could you be ready to exhibit in New York?" "Tomorrow.," I answered. So she told me: " I had decided to discontinue the work of handling, showing, all other artists except Clemente,- the gallery was really started to 'put him over,' - because of my belief in his greatness. Now I have seen your work. It complements his-there is no conflict- you both are striving toward the same end. Clemente and I have discussed it,-we want you to be the only other artist the gallery will show and promote." (Weston, p. 177).

Jose Clemente Orozco portrait by Edward Weston, Carmel, July 20, 1930.

While in Carmel, Orozco consigned a portfolio of his lithographs to the Denny-Watrous Gallery for shows beginning in late July and early September. The above portrait of Orozco was also displayed alongside other Weston studies of contemporary Mexican artists including Diego Rivera, Miguel Covarrubias, Doctor Atl, Tina Modotti and Jean Charlot. Weston wrote a profile on Orozco for The Carmelite in which he stated,

"Comparisons are unnecessary. Orozco stands alone, with the uniqueness of a great artist. His pencil or brush is capable of vitriolic satire or tender compassion, his presentation is direct: stark beauty, free from all frosting, all sugar coating. There is no compromise in Orozco, the quintessence of his subject is revealed stripped to the very bones. He has structural solidity plus emotional fire - a rare combination in contemporary artists - usually either cold from theorizing or lukewarm from weak heart or evasion. Oroszco is the visionary sweeping aside all minor issues, seeing life majestically its heights or depths, with a gesture beyond good and evil." (Weston, Edward, "Orozco in Carmel," The Carmelite, July 31, 1930, p. 3).

In October Time Magazine wrote of the events leading up to Orozco's Prometheus commission,

"The West's view of Orozco, a view of one of the finest things he has done, was made possible by the removal of some scaffolding from the dining hall of Pomona College, 40 mi. south of Los Angeles. Last winter, head of Pomona's art department was Professor Jose Pijoan, authority on Latin American art, avid Orozcoan. So long, so vigorously did he preach Orozco to the sons and daughters of Pomona that on their own initiative they invited Orozco to come west, decorate their dining hall. "We have no money," said Prof. Pijoan when Orozco arrived, "at present only $500." Artist Orozco glowered through his glasses. "Never mind about that," he said. "Have you got a wall?" When Artist Orozco returned to New York he left behind a huge ogival Michel-angelican fresco, 25 x 35 ft. representing a giant Prometheus bearing the fire of truth, in pulsating Mexican color. Wrote Critic Arthur Millier of the Los Angeles Times: "The wall has been energized by the genius of Orozco until it lives as probably no wall in the United States today." Long-legged Arnold Ronnebeck of the Denver Times was even more enthusiastic. Added Sumner Spaulding (see below), architect of Pomona's dining hall: "I feel as though the building would fall down if the fresco were removed." (From "Wall Man," Time, October 13, 1930).

Sumner Spaulding, Architect ca. 1928. Photo by Boye Studios from the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

Orozco, "Ruined House," lithograph, 1928. From Jose Clemente Orozco in the United States, 1927-1934 , p. 82.

, p. 82.

The same month the Time article was published Orozco was featured in two exhibitions of his lithographs in Los Angeles at the Los Angeles Museum and Jake Zeitlin's Book Shop. Arthur Millier's review favorably described Orozco's "Ruined House" (see above), "Grief," "Mexican Pueblo" (see below) and others and ended with the statement, "The appreciation of Orozco in this country is only beginning." ("Art Season is Under Way," Los Angeles Times, October 12, 1930, p. II-16).

Orozco, "Grief," lithograph, 1928. From Jose Clemente Orozco in the United States, 1927-1934 , p. 82.

, p. 82.

Orozco, "Mexican Pueblo," lithograph, 1928. From Jose Clemente Orozco in the United States, 1927-1934 , p. 84.

, p. 84.

The Blue Angel movie poster.

The Neutra's enjoyed von Sternberg's "The Blue Angel " in Vienna while visiting relatives during the world tour in the summer of 1930. He also secured the commission to design a house for the Viennese Werkbund Siedlung project likely around the time Ludwig Mies van der Rohe hired him to teach a fall class at the Bauhaus during his tour. This house was designed after returning to Los Angeles in 1931 and was completed in 1932. (See Richard Neutra and the Search for Modern Architecture

" in Vienna while visiting relatives during the world tour in the summer of 1930. He also secured the commission to design a house for the Viennese Werkbund Siedlung project likely around the time Ludwig Mies van der Rohe hired him to teach a fall class at the Bauhaus during his tour. This house was designed after returning to Los Angeles in 1931 and was completed in 1932. (See Richard Neutra and the Search for Modern Architecture , by Thomas S. Hines, p. 94) (Hereinafter Hines). Neutra is also likely to have seen Edward and Brett Weston's photographs on display in Das Lichtbild, a follow-up European exhibition to 1929's seminal avant-garde Film und Foto show which through Neutra's European connections and largess Edward and Brett and friend Imogen Cunningham were included. (For more see PGS and the Daybooks of Edward Weston, Volume II, California

, by Thomas S. Hines, p. 94) (Hereinafter Hines). Neutra is also likely to have seen Edward and Brett Weston's photographs on display in Das Lichtbild, a follow-up European exhibition to 1929's seminal avant-garde Film und Foto show which through Neutra's European connections and largess Edward and Brett and friend Imogen Cunningham were included. (For more see PGS and the Daybooks of Edward Weston, Volume II, California , p. 156).

, p. 156).

Neutra's 1930 book Amerika: Die Stilbildung des Neuen Bauens in den Verienigten featuring the El-Lisstzky-designed Brett Weston photo-montage on the cover and additional work by Edward and Brett was also likely in the European bookstores during his tour. (For much more on this see my PGS). Released only three years after his well-received first book Wie Baut Amerika?

featuring the El-Lisstzky-designed Brett Weston photo-montage on the cover and additional work by Edward and Brett was also likely in the European bookstores during his tour. (For much more on this see my PGS). Released only three years after his well-received first book Wie Baut Amerika? , the timing of this publication and his previously-mentioned self-promotional groundwork couldn't have been better to enhance his prestige while lecturing in Vienna, Zurich, Prague, Hamburg, Berlin, Cologne, Amsterdam and Rotterdam. (Hines, pp. 93-96).

, the timing of this publication and his previously-mentioned self-promotional groundwork couldn't have been better to enhance his prestige while lecturing in Vienna, Zurich, Prague, Hamburg, Berlin, Cologne, Amsterdam and Rotterdam. (Hines, pp. 93-96).

After leaving Europe for Los Angeles in late November 1930, Neutra took over a month stopover in New York trying to find a publisher for a book on the Lovell Health House. The book was to feature the photos of CAC member Willard D. Morgan which documented construction during Neutra's "Practical Course in Modern Building Art." (For much more on this see Mod). Despite not finding a publisher, Neutra was assuredly pleased to see his previously-mentioned Willard Morgan-illustrated Conrad Buff project featured in the November issue of the Architectural Record and likely knew by then that his Lovell Health House with Morgan photos had also been published by the Record's modernist managing editor A. Lawrence Kocher in the May 1930 issue.

These important appearances in the East Coast-based Record likely occurred partially through the coordination efforts of Pauline Schindler who was acting as publicity agent for a modernist circle of Los Angeles architects and designers. She, along with Morgan's independent submittals and recent friendship with Architectural Record assistant editor Douglas Haskell, was able to strategically place 15 articles featuring work by Neutra, Schindler, Lloyd Wright, J. R. Davidson, Kem Weber, Jock Peters, Irving Gill and others with Kocher (and Haskell) between late 1929 and 1931. (PGS and Mod).

Grand Central Palace, New York, circa 1930.

Through his aggressive self-promotion while in New York Neutra made some very important connections that would bode well for his career including, besides Kocher, Philip Johnson and his father Homer, corporate attorney for ALCOA, Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Joseph Urban, Ely Jacques Kahn, Lewis Mumford, Raymond Hood, Buckminster Fuller, Bruno Paul, Ralph Walker, and many others. Through Urban's connections, Neutra, Schindler and the rest of Pauline's clients (including Kem Weber, Jock Peters, J. R. Davidson, and Lloyd Wright) were included in the April, 1931 Architectural League of New York's 50th anniversary exhibition which was held in conjunction with the Allied Arts and Building Products Exhibition in New York's Grand Central Palace (see above). (Note: The exhibition also had the distinction of including soon-to-be Southern California modernist Albert Frey's (in partnership with Kocher) full-scale "Aluminaire: A House for Contemporary Life"). Neutra and R. M. Schindler corresponded regarding details of the show during Neutra's stay in New York. (Hines, p. 99 and note 24., p. 327 and Sheine, p. 256 and note 6., p. 284).

The majority of the Los Angeles work shown in the League's show was likely a reprise of Pauline Schindler's "Creative Contemporary Architecture" exhibition which had just completed its circuit of West Coast museums. (PGS). Weber, Davidson, Peters and Wright's work moved on the following month to the Brooklyn Museum's American Union of Decorative Artists and Craftsmen (AUDAC) exhibition and was published in the organization's first "Annual of American Design ."

."

Auditorium, New School for Social Research designed by Joseph Urban.

Neutra also met Dr. Alvin Johnson, the director of the New School for Social Research whose new building was recently completed by Urban. Through Urban's help he was also chosen by Johnson to deliver the opening three lectures in the new auditorium (see above) "to test its novel acoustics, as it were." (Life and Shape by Richard Neutra, p. 258; "R. J. Neutra Lectures Tonight," New York Times, January 4, 1931 and for much on his self-promotional efforts while in New York see Richard Neutra: Promise and Fulfillment, 1919-1932

by Richard Neutra, p. 258; "R. J. Neutra Lectures Tonight," New York Times, January 4, 1931 and for much on his self-promotional efforts while in New York see Richard Neutra: Promise and Fulfillment, 1919-1932 , pp. 193-209). Neutra lectured on "The Relation of the New Architecture on the Housing Problem," "The American Contribution to the New Architecture," and "The Skyscraper and the New Problem of City Planning." (Hines, p. 98).

, pp. 193-209). Neutra lectured on "The Relation of the New Architecture on the Housing Problem," "The American Contribution to the New Architecture," and "The Skyscraper and the New Problem of City Planning." (Hines, p. 98).

Main floor and Auditorium, Art Center Building, 65-67 E. 56th St., New York. Photo by H. Shobbrook. Bulletin of the Art Center, June 1923, p. 244.

Neutra also lectured on "The New Architecture" on January 4th at the Art Center under the auspices of the Art Center, the American Union of Decorative Arts and Crafts (AUDAC), and Contempora and January 7th at the Roehrich Museum (see below) on "New Architecture Shapes a New Human Environment in Europe, Asia and America." ("R. J. Neutra Lectures Tonight,"and "What is Going On This Week," New York Times, January 4, 1931). Neutra's Art Center lecture was likely facilitated through Los Angeles colleague Kem Weber's AUDAC connections and his critical acclaim from participating in the 1928 International Exposition of Art in Industry Exposition sponsored by Macy's in New York. (For more details see my Foundations of Los Angeles Modernism).

Roerich Museum and Master Apartment Building, Corbett, Harrison and MacMurray; Sugarman, and Berger, Associated Architects, Architectural Record, December 1929, p. 529. (From my collection).

Jose Clemente Orozco, left, and Jorge Juan Crespo de la Serna, right, at work on "Struggle in the Orient" at the New School for Social Research, January 1931. From Jose Clemente Orozco in the United States, 1927-1934 , p. 127.

, p. 127.

While spending the better part of a week lecturing at the New School for Social Research, Neutra almost certainly made contact with Orozco who was hard at work with his Prometheus assistant Crespo finishing the mural commissions secured through his dealer Alma Reed for the fifth floor lounge and dining room. (See above and below). (For much more on this important commission see Jose Clemente Orozco in the United States, 1927-1934). Neutra is also likely to have seen Weston's work on display alongside Orozco's at Reed's Delphic Studios where his one-man show ran throughout November. Frances D. McMullen's November 16th review in the New York Times headlined, "Lowly Things that Yield Strange, Stark Beauty; With His Camera Edward Weston Finds Realism in the Sea Shells and the Common Fruits of the Earth; The Prosaic Things Which Reveal New Charm."

Orozco, "Struggle in the Orient" (top) and Struggle in the Occident" (bottom). From Jose Clemente Orozco in the United States, 1927-1934 , pp. 124-5.

, pp. 124-5.

Time Magazine wrote of Orozco's return to New York from California to work on the murals,

"The East's view of Orozco is obtainable this week at the Metropolitan Museum, Manhattan. Two of his huge canvases [completed in San Francisco during the summer] are part of the loan exhibition of Mexican art circulated by the Carnegie Institute and the American Federation of Arts, sponsored by ex-Ambassador Dwight Whitney Morrow and Dr. Frederick A. Keppel. Artist Orozco himself is further downtown squatting on a scaffold in the New School of Social Research, (see above) painting great swirling designs on wet plaster with a very small brush. Beside him his master plasterer and assistant Juan Jorge Crespo, prepares the wall for Orozco to paint, two square yards at a time. "Fresco painting," explained Artist Orozco, "has much to do with the time of day. If I start one piece at ten in the morning, I must start the next piece at ten the next morning so that the colors will dry the same." (From "Wall Man," Time, October 13, 1930).

Party at Alma Reed's Delphic Studios, 1936. David Alfaro Siqueiros, upper left, Alma Reed, center, and Jose Clemente Orozco, upper right. Unidentified photographer. Enrique Riverón papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

There is a good chance Neutra may also have hooked up with Los Angeles friends John Weber, Jock Peters, Barbara and Willard Morgan and Annita Delano about this same time. The Morgans had recently moved to New York from Los Angeles into a building also occupied by Architectural Record assistant editor Douglas Haskell whom Neutra may also have met. Weber and Peters were putting the finishing touches on the interiors of the L. P. Hollander Building in collaboration with Eleanor Lemaire after completing the Bullock's Wilshire interiors the year before. Annita Delano was also in town over the Christmas holidays from her internship at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia to visit the Morgans, Lemaire, Peters and Weber and view the Hollander work. At Weber's 11th hour request, Annita and Barbara rushed a mural onto the walls the night before the store opened. It is thus highly likely that members of this group took in a Neutra lecture or two at The New School for Social Research, the Art Center and/or the recently completed Roerich Museum in early January. (For more details see my Foundations of Los Angeles Modernism).

Neutra's exhaustive New York networking effort undoubtedly helped secure his place in the Museum of Modern Art's seminal Modern Architecture International Exhibition the following year and consequently his legacy as well. Correspondence and documents pertaining to the planning of the exhibition indicate that Neutra's inclusion was decided upon sometime during January, shortly after his return from a Cleveland interlude at White Motors Company where he was designing an aluminum bus in collaboration with the MoMA show curator Philip Johnson's father Homer's ALCOA. (Note: Homer Johnson was also a deep pockets patron of the exhibition and was secretary of the supervisory committee. See for example Riley , pp. 30-31, 39 and 214).

, pp. 30-31, 39 and 214).

Arthur Millier's January 25th "News of the Art World" column reported that a homesick Richard Neutra was on his way home from his world tour after giving a series of lectures at New York's New School for Social Research. ("Neutra Homeward Bound," Los Angeles Times, January 25, 1931, p. III-5). The Times also reported on April 15th that Neutra would receive a welcome home at the next evening's California Art Club monthly meeting. ("California Art Club Banquet Tomorrow," Los Angeles Times, April 15, 1931, p. 20). A couple of weeks later Neutra lectured at the Club on "Tendencies in Modern Architecture" sharing his findings from his recent globe-trotting tour. ("Art Club Will Hear Lecturer," Los Angeles Times, May 4, 1931, p. I-2). Dione Neutra accompanied herself on the cello (see below) singing folk songs from India in conjunction with a slide lecture by Joseph Choate on his recent India travel experiences at the CAC's monthly dinner meeting on November 20th at Barnsdall Park. ("Club to Hear of India," Los Angeles Times, November 19th, 1931, p. I-2). She must have had great feelings of nostalgia performing in Wright's Barnsdall House after entertaining at Taliesin seven years earlier. (see two below).

Dione Neutra promotional letterhead designed by Richard Neutra, 1928. From Richard Neutra: Promise and Fulfillment, 1919-1932 , p. 176).

, p. 176).

From left, Frank Lloyd Wright, Richard Neutra, Sylva Moser with baby, Kameki Tsuchiura, Nobu Tsuchiura, Werner Moser on the violin and Dione Neutra with cello in the living room at Taliesin, 1924. From Richard Neutra: Promise and Fulfillment, 1919-1932 , p. 52).

, p. 52).

During May, 1931 Neutra had a visitation from the industrialist and patron of "International Style" architecture C. H. van der Leeuw with whom he met while lecturing in Basel during his world tour. VDL invited Neutra to Rotterdam to stay at his state-of-the-art modern home, visit his new Van Nelle Factory and lecture. Ironically, Van der Leeuw had also just lectured at the New School for Social Research on April 27th on his new factory designed by J. A. Brinkman and L. C. van der Vlugt and likely viewed Neutra's work on display at the Architectural League's concurrent exhibition. ("A Stir is Caused by Secessionists Who Have Put on a 'Rejected Architects' Show - 'International Style' Compared With Work Exhibited by Architectural League," New York Times, April 26, 1931, p. X10).

Neutra provided van der Leeuw a tour of modernist architecture around Los Angeles including his Jardinette Apartments and Lovell Health House and reciprically arranged a speaking engagement for him on "Modern Factory Architecture" at the Electric Club. ("C. H. Van der Leeuw Visitor at Electric Club: Guest from Holland talks on architecture, Los Angeles Times, May 19, 1931, p. I-8). When VDL learned that Neutra as yet had no place of his own he immediately granted him a loan to begin work on what was to become the now iconic VDL Research House in Silver Lake. Neutra put van der Leeuw in contact with Philip Johnson on his way back to New York and Europe who in turn arranged a lunch meeting for him with MoMA Trustee and Treaurer, Mrs. John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (Riley , pp. 38 and 205).

, pp. 38 and 205).

Chouinard School of Art course brochure for Neutra and Schindler'a course "Fundamentals of Modern Architecture," July-August 1931.

As the Neutras excitedly began searching for a lot for the VDL Research House during the summer of 1931, Neutra and Schindler co-taught "A Course in the Fundamentals of Modern Architecture" at the Chouinard School of Art which was repeated in the fall. (News of the Art World: Schools and Lecture Courses, Los Angeles Times, October 11, 1931, p. III-8). Among his credentials Neutra listed his class at the Bauhaus, attendance at the CIAM conference in Brussells and his lectures at New York's New School for Social Research, all from his 1930-1 world tour. (See class brochure above). Also on the Chouinard faculty at the time were Orozco mural sidekick Jorge Juan Crespo, Hans Hofmann, Millard Sheets, Phil Dike, Arthur Millier and soon-to-be CAC President Robert Merrell Gage. Erstwhile Rivera mural assistant Crespo also lectured at the California Art Club three weeks after Neutra on May 25th on "Mural Painting in Mexico." ("Painter Will Address Forun," Los Angeles Times, May 25, 1931, p. II-10).

Portrait bust of Josef von Sternberg by David Edstrom and caricature of Edstrom by von Sternberg. (Millier, A., "Creative Minds Unite as Sculptor and Model," Los Angeles Times, July 26, 1931, p. III-18

About the time of the Neutra-Schindler Chouinard class Arthur Millier wrote a lengthy and enthusiastic review of California Art Club member and lecturer David Edstrom's bust of Josef von Sternberg and the movie director's extensive art collection. A photo of the Edstrom's bust and a caricature of Edstrom by von Sternberg accompanied the review. (See above). Millier wrote,

The plaster cast of the bust was exhibited in January 1932 in the French Room at the Hollywood Plaza Hotel, long-time residence of the artist which was directly across the street from the Braxton Gallery. (See above). The bronze made from the cast was concurrently on display at the new Stendahl Galleries on Wilshire Blvd. (See below).

During this same summer of 1931, F. K. Ferenz and Jorge Juan Crespo were bringing to fruition their scheme to create the Plaza Art Center in the old Italian Hall (see below) at 53-55 Olvera Street. The Center was part of a plan championed by Christine Sterling to create an art and tourist center in what had been the long-neglected heart of the original city. Fellow Viennese emigre Ferenz commissioned R. M. Schindler to draw up plans for remodeling the building's arcade shops including a new restaurant which unfortunately was never built. Future Schindler client, CAC member and lecturer and fellow Viennese emigre, Gisela Bennati, also a creative designer of women's clothing and later instructor at Otis Art Institute, opened an art shop in one of the arcade stores. (See "Plaza Art Center to Open", August 16, 1931 Los Angeles Times, "Feminine Attire Art Club Topic," Los Angeles Times, May 18, 1929, I-22; "Embassy Restaurant and Arcade," 1931 project and "Mountain Cabin for Gisela Bennati, Lake Arrowhead, 1934-7", in Schindler by David Gebhard, pp. 96, 200). Willy Pogany, a famous Hungarian painter and illustrator recently relocated from New York and then working for United Artists, was mentioned as promising to do a historical fresco on the Olvera Street facade of the building which went unrealized.

"David Edstrom is one of the finest living portrait sculptors. Josef von Sternberg is unique among motion-picture directors. ... The character of the short man who willed to become a director - and became a great one - is expressed entirely in a rythmic interplay of sculptured planes that are not nature at all but a magnificent clear counter-point of forms; curving forms, flat forms, large and small ones. And the sum of these makes something that is at one moment a delightful object in polished brass, the next the sternly willful image of a commanding, yet sensitive man." (Millier, Arthur, "Creative Minds Unites as Artist and Sculptor," Los Angeles Times, July 26, 1931, p. III-18). (Author's note: Edstrom was a habitue of Gertrude Stein's salons in Paris as early as 1906. See "Sister and Brother: Getrude and Leo Stein" by Brenda Wineapple, pp. 258-9).

David Edstrom, Josef Von Sternberg, plaster cast, 1931. From California Arts & Architecture, January 1932, p. 6.

The plaster cast of the bust was exhibited in January 1932 in the French Room at the Hollywood Plaza Hotel, long-time residence of the artist which was directly across the street from the Braxton Gallery. (See above). The bronze made from the cast was concurrently on display at the new Stendahl Galleries on Wilshire Blvd. (See below).

Wilshire Blvd. looking west with new Stendahl Galleries in the Clark Building designed by Morgan, Walls & Clements at 3306 Wilshire Blvd. under construction just east of Bullock's Wilshire at lower left. Photo from Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

During this same summer of 1931, F. K. Ferenz and Jorge Juan Crespo were bringing to fruition their scheme to create the Plaza Art Center in the old Italian Hall (see below) at 53-55 Olvera Street. The Center was part of a plan championed by Christine Sterling to create an art and tourist center in what had been the long-neglected heart of the original city. Fellow Viennese emigre Ferenz commissioned R. M. Schindler to draw up plans for remodeling the building's arcade shops including a new restaurant which unfortunately was never built. Future Schindler client, CAC member and lecturer and fellow Viennese emigre, Gisela Bennati, also a creative designer of women's clothing and later instructor at Otis Art Institute, opened an art shop in one of the arcade stores. (See "Plaza Art Center to Open", August 16, 1931 Los Angeles Times, "Feminine Attire Art Club Topic," Los Angeles Times, May 18, 1929, I-22; "Embassy Restaurant and Arcade," 1931 project and "Mountain Cabin for Gisela Bennati, Lake Arrowhead, 1934-7", in Schindler by David Gebhard, pp. 96, 200). Willy Pogany, a famous Hungarian painter and illustrator recently relocated from New York and then working for United Artists, was mentioned as promising to do a historical fresco on the Olvera Street facade of the building which went unrealized.

Crespo curated the inaugural exhibition on "Contemporary Mexican Art" which opened on September 1st. Due to his solid ties with Orozco and Merle Armitage he was able to secure numerous paintings, drawings and prints from Alma Reed's Delphic Studios and the Weyhe Gallery in New York respectively. Weston friends Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros headlined the exhibition which also included work by another close Weston friend Jean Charlot, Roberto Cueva del Rio, Pablo O'Higgins, Crespo and his son Gilberto and many others. The show was sponsored by the Mexican Consulate and the guests of honor were Christine Sterling, Alma Reed, Willy Pogany and Arthur Millier. In his review of the show Millier wrote,

"Orozco has several superb wash drawings, notably the dramatic "Requiem" (see below) and a small watercolor of peasant women carrying wood past a pink church wall, which is a masterpiece of his art. ... By D. A. Siqueiros is a single small picture, "Prisoner's Wife," which proclaims this artist one of the masters of Mexico." ("Mexican Art Seen at Plaza," Los Angeles Times, September 6, 1931, p. 12).

Orozco, "Requiem," ink on paper, 1926-28. From Jose Clemente Orozco in the United States, 1927-1934, p. 29.

An expanded version of the Pauline Schindler's previously-mentioned "Contemporary Creative Architecture in California" exhibition under the new title "Contemporary Architecture, Decoration and Store Design" was the second exhibition at the new Plaza Art Center (see photo below) in October in the building's newly remodeled second floor gallery space run by the Plaza Art Club. (See "Roundabout the Galleries", L.A. Times, Oct. 11, 1931 and PGS).

Italian Hall, Plaza Art Center, Olvera Street as it looks today. Note the 1932 David Siqueiros mural "Tropical America" on the side of the building.

Von Sternberg admired work by Peter Ballbusch, a Swiss sculptor and later chief of MGM's montage department, and Richard Kollorsz, a pupil of Otto Dix who was then painting scenery at Paramount and employed them as assistants on his films. (They both would later assist Siqueiros in creating Tropical America at the Plaza Art Center). In February 1932, soon after they finished work as design assistants on von Sternberg's Shanghai Express , he sponsored a joint exhibition of paintings by Kollorsz and sculpture by Ballbusch at the Plaza Art Center. (Millier, Arthur, "Brush Strikes," Los Angeles Times, February 14, 1932, p. II-21 and Von Sternberg

, he sponsored a joint exhibition of paintings by Kollorsz and sculpture by Ballbusch at the Plaza Art Center. (Millier, Arthur, "Brush Strikes," Los Angeles Times, February 14, 1932, p. II-21 and Von Sternberg by John Baxter, p. 162). Another new friend was Austrian-born architect Richard Neutra whom he wrote in February 1932 regarding a commission for his personal residence. They most likely first met at the Braxton Gallery during the Blue Four exhibitions in 1930. The two would sit up all night discussing art. Their conversations inspired von Sternberg to seek a site in the San Fernando Valley where Neutra could build him a house not far from where he filmed Shanghai Express

by John Baxter, p. 162). Another new friend was Austrian-born architect Richard Neutra whom he wrote in February 1932 regarding a commission for his personal residence. They most likely first met at the Braxton Gallery during the Blue Four exhibitions in 1930. The two would sit up all night discussing art. Their conversations inspired von Sternberg to seek a site in the San Fernando Valley where Neutra could build him a house not far from where he filmed Shanghai Express . (Baxter, p. 172).

. (Baxter, p. 172).

Diego Rivera and Ione Robinson, National Palace, Mexico City, 1929. From A Wall to Paint On by Ione Robinson, p. 22.

by Ione Robinson, p. 22.

Although von Sternberg never showed much interest in politics, he frequented the John Reed Clubs, a network of Marxist discussion groups supported by the Communist Party. At their shows and auctions, he bought paintings by Diego Rivera and Manuel Orozco. (Baxter, p. 164). Through Kollorsz he met Ione Robinson, (see above) a remarkably precocious artist who had traveled to Mexico at the age of 19 in 1929 to work with Rivera on his National Palace murals. ("Girl Artist Back from Paris Study; Talented Los Angeles Miss Plans Work as Mexican Master's Study," Los Angeles Times, May 17, 1929, p. II-1, and "Vandals Mar Murals; Los Angeles Woman Will Repair Noted Mexican's Paintings," Los Angeles Times, August 30, 1929, p. 2).

Robinson, who had also studied at the Otis Art Institute under CAC member Edouard Vysekal while still in high school and at the age of 17 had also apprenticed with Rockwell Kent and Paul Frankl in New York. During 1927-8 she traveled throughout Europe and in 1930 exhibited at the Alma Reed's Delphic Studios, the Weyhe Galleries, and the New York Art Center.

in New York. During 1927-8 she traveled throughout Europe and in 1930 exhibited at the Alma Reed's Delphic Studios, the Weyhe Galleries, and the New York Art Center.

Ione Robinson, Mexico City, 1929 by Tina Modotti. From IoneRobinson.org.

While in Mexico City Rivera introduced Robinson to former Edward Weston lover and partner Tina Modotti with whom she immediately moved in with. Weston and Modotti had spent most of 1923-26 together in Mexico. (For more on the complex Weston-Modotti relationship see my "Edward Weston Remembers Tina Modotti"). Through Modotti Ione met communist party ideologue and John Reed Club organizer Joseph Freeman, later the editor of New Masses and founding editor of the Partisan Review, who quickly became obsessed with her. Shortly thereafter she was seduced by Rivera which enraged Freeman. (Tina Modotti: Photographer and Revolutionary by Margaret Hooks, p. 195-6). First infatuated by Rivera, Ione inscribed the verso of the below photo of herself taken while she was studying in France in 1927-8 "For Diego with all my love." Coincidentally, during her Paris sojourn Ione met and studied with later Mexican muralist Isamu Noguchi (and likely Marion Greenwood) and became a life-long friend. (Hooks, p. 44).

by Margaret Hooks, p. 195-6). First infatuated by Rivera, Ione inscribed the verso of the below photo of herself taken while she was studying in France in 1927-8 "For Diego with all my love." Coincidentally, during her Paris sojourn Ione met and studied with later Mexican muralist Isamu Noguchi (and likely Marion Greenwood) and became a life-long friend. (Hooks, p. 44).

Ione Robinson, France, 1927-8. Photographer unknown. From Frida Kahlo: Her Photos edited by Pablo Ortiz Monasterio, p. 271.

edited by Pablo Ortiz Monasterio, p. 271.

Freeman and Rivera quickly mended fences for the good of the Communist Party as Rivera, soon to marry Frida Kahlo, was successful in shifting the focus of the young Ione's affections from himself to Freeman. (Joseph Freeman letter to Diego Rivera, unsent, October 1929, Box 34, Folder 13, Freeman Papers, Stanford). In 1929 both Ione and Freeman sat for Tina Modotti portraits and soon began a short-lived, tumultuous marriage. (Hooks, pp. 208-9). (Author's note: Freeman also had his portrait taken by Edward Weston in Carmel in 1933 while visiting his then lover Ella Winter while she was organizing the Carmel John Reed Club. (Edward Weston letter to Joseph Freeman, 1933, Box 41, Folder 2, Freeman Papers, Stanford).

Joseph Freeman by Tina Modotti, 1929. From Hooks, p. 208.

After her return to Los Angeles from Mexico and New York in 1929 Ione exhibited her work at Jake Zeitlin's Book Shop and the Los Angeles Museum (see below for example). She featured a Rockwell Kent drawing of herself on the cover of her exhibition catalog. She was also promised an exhibition at the Stendahl Gallery. ("Current Art Exhibitions," Los Angeles Times, December 1, 1929, p. 21 and letter to husband Joseph Freeman, Joseph Freeman Papers, December 1929, Hoover Institute, Stanford).

"Art: Three Hats," Los Angeles Times, December 1, 1929, p. VIII-4. Photo by Tina Modotti.

After divorcing Freeman and again back in Los Angeles in early 1931, Ione met for the first time, and possibly had a liaison with, Edward Weston at a "memorable" party thrown in his honor at the Palos Verdes Beach Club organized by longtime friends Ramiel McGehee, Mere Armitage and Jake Zeitlin. Ione had excitedly attended the opening of Weston's first New York exhibition at Alma Reed's Delphic Studios the previous November and wrote Freeman that Alma was very upset he did not attend. (Ione Robinson letter to Joseph Freeman, n.d., ca. October 17, 1930. Joseph Freeman Papers, Hoover Institute, Stanford Universtiy). Weston wrote of the occasion,

"Arriving late, I stepped into an enormous room, - one long table, feast-laden, extended the full length. In front of the fireplace in which the great eucalyptus logs blazed, a regiment of lobsters, in uniforms red, awaited the attack. Old friends greeted me, - Merle, Arthur, Jose, Fay, Jake, and a new one, Ione Robinson. I had but entered the room when someone slipped me a glass of scotch (real) and so the fun began. Ramiel, the perfect host, bustled vigilantly everywhere, hawk-eyed to further every want, to provoke all means to joy." (Daybooks, February 21, 1931). (Author's note: Ione met Rockwell Kent collector Merle Armitage while working for Kent in New York in early 1928. Kent was then also editor of Creative Art Magazine and it was likely through the Armitage-Kent connection that much work from the Weston-Schindler circle was published in the magazine including work by Edward Weston, Richard Neutra, Pauline and R. M. Schindler, Kem Weber, Boris Deutsch and many others.)

A couple months later Robinson again traveled to Mexico for more work on Rivera's National Palace murals after winning a Guggenheim fellowship, secured largely through a 1930 exhibition of her work curated by Orozco at Alma Reed's Delphic Studios in New York. ("Guggenheim Fellowship Awarded to Girl Artist," Los Angeles Times, March 30, 1931, p. II-1). While in New York she befriended Zohmah Day, another aspiring artist from Los Angeles and invited her to follow her to Mexico where Zohmah also assisted on the Rivera murals.

Ione Robinson by Lola Alvarez Bravo, n.d. From back cover of A Wall to Paint On by Ione Robinson, E. P. Dutton and Co., New York, 1946.

During this period Ione posed for Lola Alvarez Bravo (see above) and she and Zohmah met yet another close Weston friend, Jean Charlot, and Sergei Eisenstein (see below) a Russian movie director with ties to Siqueiros, Dudley Murphy and Josef von Sternberg (see below). (Mexico Through Russian Eyes, 1806-1940 by William Harrison Richardson, p. 169, Dudley Murphy, Hollywood Wild Card

by William Harrison Richardson, p. 169, Dudley Murphy, Hollywood Wild Card by Susan Delson, University of Minnesota Press, 2006, p. 214 and Baxter, various). It was also likely around this time that Robinson painted the below portrait of Day.

by Susan Delson, University of Minnesota Press, 2006, p. 214 and Baxter, various). It was also likely around this time that Robinson painted the below portrait of Day.

Ione Robinson and Sergei Eisenstein, Tetlapayac, June 1931. From A Wall to Paint On by Ione Robinson, p. 88).

by Ione Robinson, p. 88).

Zohmah Day by Ione Robinson, 1931. Provenance from the Stewart Gallery.

Charlot and Zohmah met at a dinner party organized by Ione and Zohmah at their house in Coyoacan during the summer of 1931 and finally married in 1939. (Author's note: Before leaving for Mexico earlier that year to film "Que Viva Mexico!' Eisenstein sat for a portrait with Brett Weston at his studio in Frank Lloyd Wright's Storer House which he was then sharing with Pauline Schindler and Galka Scheyer.)

Sergei Eisenstein, Marlene Dietrich and Josef von Sternberg, Hollywood, 1930. From A Certain Cinema.

Robinson, who had also studied at the Otis Art Institute under CAC member Edouard Vysekal while still in high school and at the age of 17 had also apprenticed with Rockwell Kent and Paul Frankl in New York, traveled throughout Europe and exhibited at the Alma Reed's Delphic Studios, the Weyhe Galleries, and the New York Art Center. She heard Siqueiros speak on numerous occasions in Mexico City in 1931 and visited him in Taxco in either December 1931 or January 1932. In a January letter to her mother Ione wrote,

in New York, traveled throughout Europe and exhibited at the Alma Reed's Delphic Studios, the Weyhe Galleries, and the New York Art Center. She heard Siqueiros speak on numerous occasions in Mexico City in 1931 and visited him in Taxco in either December 1931 or January 1932. In a January letter to her mother Ione wrote,

"At Taxco we stopped to call on Siqueiros. I found him living with Blanca Luz in a house on the top of a hill. A large red paper star-lantern hung on the porch! I asked Siqueiros what he was doing. He told me that he had organized all the little boys in Taxco to watch the cars of the tourists. If a tourist refused to have his car watched by this "boys' union," then their tiress would be pierced with long nails! Wherever Siqueiros goes, trouble is bound to follow." (A Wall to Paint On by Ione Robinson, p. 195).